|

|

|

Editorials | July 2005 Editorials | July 2005

Mexico's Pride in Memín Pinguín

Enrique Krauze - Washington Post Enrique Krauze - Washington Post

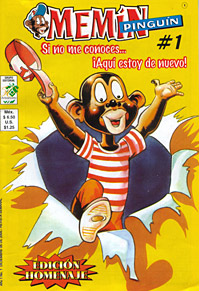

| | A re-issue of the controversial "Memin Pinguin" comic book went on sale last week in Mexico - email BanderasNews for a copy at: Menin@BanderasNews.com. |

The United States has been an independent nation for 229 years. Has it ever had a Native American or African American president? No. Mexico, on the other hand, can point to two presidents of Native American origin who were as decisive in the history of their country as Abraham Lincoln or Theodore Roosevelt in the United States: Benito Juárez, a Zapotec Indian who learned Spanish as a second language, and Porfirio Díaz, whose mother was a Mixtec Indian.

Other famous leaders in Mexico's history were African American in their origins: José María Morelos, for instance, the second commander of the Mexican rebels in their War for Independence (1810-1821), and his subordinate, Gen. Vicente Guerrero, who became president eight years after Mexico won its independence from Spain. In the 20th century, only two presidents were of pure-blooded Spanish descent, José López Portillo and Vicente Fox. The rest were mestizos, of mixed ancestry.

Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton and even President Bush have recently complained that a Mexican postage stamp bearing the image of Memín Pinguín, a dark-skinned comic-book character, is an offensive racist caricature. The reality is different and worth clarifying. Memín Pinguín is a very popular personage of Mexican historietas, a kind of comic book read by people of all ages, and especially by the poor and relatively uneducated.

To Americans, the figure, with his exaggerated "African" features, resembles racist U.S. cartoons. To Mexicans, he is a wisecracking, likable character, representing not racial discrimination but rather the egalitarian possibility that all groups can live together in peace.

During the 1970s and '80s, his historietas sold over 1 1/2 million copies because they touched an authentic chord of sympathy and tenderness among poorer people.

The stamp's misinterpretation may have been partially caused by the recent careless and unfortunate language lapse by Fox when, in defending the very real worth of Mexican labor to the U.S. economy, he said that Mexicans take jobs "not even blacks want to do," which quite understandably offended African Americans.

But Jackson and Sharpton would find much to respect were they to look at some essential facts of African American history in Mexico. The terrible demographic catastrophe among the Native Americans, caused by rampaging epidemics of European diseases, was an important motive for the importation of African slaves to Mexico, where they were used in hard labor in such places as the sugar cane plantations.

But in contrast to the Indians, who were officially freed from local slavery in 1551 but were still subjected directly to the king of Spain, Africans could buy their freedom and give birth to children who were free to marry anyone of any racial origin. Moreover, they were able to move through colonial society with a certain ease and even some advantages.

To be sure, within the society of New Spain, they and their descendants (usually free and intermarried with Indians and mestizos) were not admitted to certain occupations and offices limited to people of pure-blooded Spanish descent. But they could work freely in tropical agriculture and skilled occupations, especially as blacksmiths, painters, sculptors, carpenters, candle-makers and singers in the churches. In the colonial society of New Spain, men and women of color mixed easily with the rest of the population.

Certainly Mexico has at times shown racism toward its Indian population, especially in areas of the southeast such as Chiapas, and toward Chinese immigrants in the north. But the great difference between Mexico and the English colonies was that racism had far less effect on the population's ethnic composition. And the suppression of slavery in Mexico was relatively rapid and for almost two centuries has formed an integral part of every Mexican constitution.

Mexicans, especially young people, have responded with massive enthusiasm to the Memín Pinguín stamp. They see it not as a racist slur but a highly pleasing image of popular culture. If Memín Pinguín were a real person, I believe he could win the coming presidential election. |

| |

|