|

|

|

Editorials | July 2005 Editorials | July 2005

The Supremacy of the Super-Citizen

William Rivers Pitt - t r u t h o u t William Rivers Pitt - t r u t h o u t

| "Unless you become more watchful in your States and check this spirit of monopoly and thirst for exclusive privileges, you will in the end find that the most important powers of Government have been given or bartered away, and the control of your dearest interests have been passed into the hands of these corporations."

- Andrew Jackson, farewell address, March 4, 1837 |

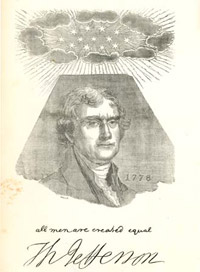

The document reads, "All men are created equal." When those words were first put to paper, of course, the literal meaning of the phrase did not match what was written. A more accurate sentence would have read, "All white land-owning men are created equal," but despite the inherent racism and misogyny buried in the original meaning, the words had magic and power enough to lay the groundwork for 200 years of progress.

The words as written became the basis for reform after reform, for the strengthening of the rights of minorities, women, and basically anyone who would be made subservient to anyone else. The struggle took a long time, and continues today with much remaining to do before that equality is truly achieved, but the strength of those words as written has been proven time and again to be more than a match for anyone who would stand on the neck of a fellow citizen.

That's what the billboard reads, anyway. That's the propaganda, the myth, the way we rock ourselves to sleep at night. The truth is significantly different, however, and is at the root of just about everything that has gone wrong with this great democratic experiment.

We are not all created equal, in fact. This inequality is not based on race, or sex, or religion, but upon the slow development of a body of laws that have created and empowered a breed of super-citizens which rule over every aspect of our lives, almost completely beyond the reach of justice. These super-citizens exist today under the familiar name "corporation."

But wait, a corporation is basically a company, right? A corporation is a non-living entity, a group of people endeavoring to make money in a business enterprise or non-profit organization, right? Wrong. A corporation is indeed a non-living entity, a group of people looking to make money. But thanks to a Supreme Court decision, corporations are also actual living entities in every legal sense of the word, with all rights and privileges of citizenship - and several more besides - intact.

A Short History of Corporations

The word "corporation" comes from the Latin "corpus," or "body." The Oxford English Dictionary defines "corporation" as "a group of people authorized to act as an individual." The history of corporations in America is intertwined with the story of the revolution that birthed this nation. British corporations in colonial America were rebelled against vigorously as representatives of the Crown, which they were.

Many of the principal actors in the American revolution, among them George Washington, wanted to throw off British rule because they felt their ability to conduct commerce freely was being disrupted. When 60 Boston residents hurled the tea into Boston Harbor in 1773, it was an attack specifically upon the economic power and supremacy of a corporation called the British East India Tea Company, which had been undercutting the profits of colonial merchants thanks to the passage of the Tea Acts.

After the revolution, and for a hundred years, the American people bore a deep distrust of the corporation, and corporations were regulated severely. Corporate charters were created by individual states, and those states had the power to revoke that charter if the corporation was deemed to be acting against the public good or had deviated from its charter. Corporations were not allowed to own other corporations, nor were they allowed to participate in the political process.

Very slowly over that 100 years, however, the power of the corporation began to grow. In the 1818 Supreme Court case "Dartmouth College v. Woodward," Daniel Webster, advocating for Dartmouth, argued passionately for the power of corporations in regards to property rights. The Court sided with Webster and corporate rights, stating: "The opinion of the Court, after mature deliberation, is that this corporate charter is a contract, the obligation of which cannot be impaired without violating the Constitution of the United States. This opinion appears to us to be equally supported by reason, and by the former decisions of this Court."

A good deal of hell was raised after this decision, with many citizens and state legislatures standing upon the right of a state to repeal or amend a corporate charter. Seven years later, however, another Supreme Court case buttressed the power of the corporation with their decision in "Society for the Preservation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts v. Town of Pawlet." The Society was seeking to protect its colonial-era property grants in Vermont, while Vermont was seeking to revoke those grants. The Court decided in favor of the Society, and explicitly extended the same protections to corporation-owned property as are enjoyed by property-owning natural persons.

Corporations in America began to become truly powerful with the rise of the railroads. Railroads were the lifeblood of the growing nation, carrying both agriculture and industry from one side of the country to the other. This was a highly profitable enterprise, and railroad corporations began to exert heavy influence on both state and federal leaders. Corporate attorneys boldly asserted the precedents set in the Dartmouth and Society Supreme Court decisions, demanding that corporations deserved to have at least some of the rights of natural persons. Meanwhile, attorneys loyal to the railroads began to rise through the ranks of the Judiciary, finally finding seats on the highest bench.

This process came to a final head in 1886, when the Supreme Court heard the case "Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad." Arguments over the rights of corporations as persons had been raging for decades, and Chief Justice Waite pounded home the nail: "The court does not wish to hear argument on the question whether the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to these corporations. We are all of the opinion that it does."

"We are all of the opinion that it does."

The pertinent section of the Fourteenth Amendment reads, "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

Before the Santa Clara decision, this amendment applied only to living, breathing people. After Santa Clara, it applied also to massively wealthy corporations, groups of people authorized to act as individuals, but beyond the kinds of legal liabilities natural persons are subject to. The Santa Clara decision, and subsequent decisions affirming it, created the formidable distinction between the citizen and the super-citizen.

Both have purchasing power, both can give money to whomever or whatever they please, but the difference lies in the extent to which this can be done. A natural person can buy a house and give money to a politician. A wealthy corporation, on the other hand, can buy a thousand houses and give money to a thousand politicians. In other words, a corporation which enjoys the same rights as a natural person has a thousand times the power and influence of a natural person over the economics and politics of the country. That is a super-citizen.

Because these super-citizens can exert so much power, their rights have been dramatically extended over the years. In the 1950s, for example, corporations paid some 40% of the taxes in this country. They flexed their muscles and exerted their influence, and by 1980 were paying only 26% of the taxes in this country. The Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 slashed that payment to 8%.

The economic boon enjoyed by these super-citizens is augmented by the fact that regular citizens' tax dollars are used by the government to purchase goods and services from corporations involved in the production of weapons, petroleum, timber and agricultural products. Corporate perks like jets, elaborate headquarters, public relations firms, and executive retreats are all tax write-offs; the regular citizen, by contrast, pays for their perks with after-tax dollars. When a corporation screws up and destroys an ecosystem with a toxic spill, corporate liability shields protect them from financial and legal punishment, and the cost of the clean-up is borne by the tax dollars of the regular citizen.

Today, corporations control almost every aspect of what we see, hear, eat, wear and live. Every television news media organization is owned by a small handful of corporations, which use these news outlets to filter out information that might be damaging to the parent company. Agriculture in America is controlled by a small group of corporations. One cannot drive a car, rent a van, buy a house or deliver goods in a business transaction without purchasing insurance from a corporation. Getting sick in America has become a ruinously expensive experience because corporations now control even the smallest functions of the medical profession, and have turned the practice of health care into a for-profit industry.

The influence these super-citizens hold over local, state and national politics is the reason why so many privileges have been afforded to them. This influence has existed to one degree or another for decades. Yet it was another Supreme Court decision, handed down in 1976, that allowed these super-citizens to establish a strangle-hold on our politics and government institutions.

The Supremacy of the Super-Citizen

In 1976, the case "Buckley v. Valeo" came before the Supreme Court. Senator James Buckley, former Senator and Presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy, and several others had filed suit to challenge the constitutionality of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) and the Presidential Election Campaign Fund Act. Among the defendants were Francis Valeo, Secretary of the Senate and ex officio member of the newly-created Federal Election Commission, as well as the Commission itself.

The final Supreme Court decision split a number of legal hairs. The decision upheld the constitutionality of limiting political contributions to candidates, and the disclosure and record-keeping requirements established by FECA. The aspects of FECA deemed unconstitutional, however, became the basis for the supremacy of the super-citizen. In short, the Court decided that limiting the amount of money a candidate could spend was a violation of the First Amendment. In other words, the spending of campaign money was equated with the right of free speech.

On the surface, the decision makes sense. Because so much of modern political campaigning involves television and radio advertisements, direct mailing of campaign literature, extensive travel and lodging and staff payrolls, and because all these things cost money, a limitation on campaign spending necessarily restricts the ability of a candidate to practice free speech in the political realm.

The danger, of course, was that corporations would take advantage of the new spending freedoms enjoyed by politicians and flood them with influence-creating cash. The Court attempted to address this concern by upholding the limits on contribution amounts, stating that these limitations were the "primary weapons against the reality or appearance of improper influence stemming from the dependence of candidates on large campaign contributions."

The Court's attempt to address this concern failed, in no small part because of the existence of so-called "soft money." Soft money was supposed to be cash given to political parties for "party-building activities" rather than for the direct support of candidates and campaigns. Soft money contributions were not subjected to limitations, allowing super-citizens to flood outrageous amounts of money into the process. Because the soft-money rules were so vague, and because soft money contributions were so huge, the money was invariably directed towards the support of individual candidates. The politicians became corporate entities, commodities bought and sold by the super-citizens.

The passage in 2002 of the Campaign Reform Act did little to cut into the massive influence in politics enjoyed by the super-citizens. The Campaign Reform Act made most soft money contributions illegal but created a loophole large enough to sail a British tea ship through, with the enshrinement of 527 groups as political entities. 527s are tax-exempt organizations created to influence the nomination, election, appointment or defeat of political candidates.

The soft money previously given to political parties goes now to these groups, and these groups enjoy umbilical connections to the parties and candidates they work in favor of. In other words, nothing really changed, and the influence of the super-citizens was undiminished. The Campaign Reform Act also raised the hard money contribution limit from $1,000 to $2,000, thus doubling the ability of super-citizens to exert direct financial influence upon candidates and office-holders.

Today, virtually every politician holding national office is financially beholden to a corporation. Beyond the favorable tax status for corporations established by these owned politicians, the effects of this ownership are felt by average citizens every day.

Foreign policy is all too often decided by corporate considerations, and these decisions often lead to war. The air we breathe, the food we eat and the water we drink is contaminated by pollutants that corporations are legally allowed to spew, thanks to the legislative protections created by corporate-owned politicians. Draconian sentencing rules created by legislators that incarcerate millions of Americans - think "The War on Drugs" specifically - have as much to do with the influence of the corporate-controlled prison industry as with anything else.

This list goes on and on. Super-citizens define our reality by controlling the information we receive via television, newspaper and radio. Super-citizens make sure that information casts them in a favorable light. Super-citizens pound us with advertising and thus maintain the fiction that spending money on products defines the nature of a person.

The best and brightest are drafted out of law school to work for corporate defense firms for six-figure salaries, thus ensuring that super-citizens enjoy a level of legal defense not available to anyone else. Many of these corporate attorneys graduate to the bench, where they extend the influence of super-citizens across all levels of the judicial branch.

More than anything else, however, super-citizens control the ways and means of government at every level. They bought it, they own it, and they make sure it does their bidding. The needs, requirements and best interests of the average citizen do not enter into the equation.

Created Equal

Arguments can be made that corporations are good for the economy and the country. They can get things done with a speed and efficiency not often found in the bureaucracies of government. When the country had to get itself ready to fight World War II, for one example, it was the industrial and manufacturing corporations that produced the means to achieve victory beyond anyone's expectations.

In the final analysis, however, the influence held by these entities is antithetical to the fundamental ideals of the nation. We are not all created equal, and within that inequality lies the potential for enormous evil. Consider the case of I.G. Farben, the industrial giant that was the financial core of the Nazi regime. Farben produced the gas used in the concentration camps, and made lucrative use of slave labor in the camps. Before the war, Farben worked hand-in-hand with a number of powerful American corporations, the most prominent of which was Standard Oil.

In the aftermath of World War II, the crimes committed by Farben were considered so enormous that many wanted the corporation to be utterly destroyed. Instead, Farben was split into several smaller entities, several of which still exist. Millions of Americans purchase aspirin from Bayer, a company that was once part of Farben. Commercials for BASF tell us that company makes the products we buy better, but do not tell us that BASF was once part of Farben. It speaks to the power enjoyed by corporations that Farben, the company that forced concentration camp laborers to manufacture the Zyklon-B used to exterminate them, and which was the backbone of Nazi financial power, was not destroyed out of hand once the war was over. Farben is still with us. Its charter has merely been changed.

Are all corporations on the moral level of I.G. Farben? Certainly not. Many corporations work for the public good, and many that work for their own enrichment do not necessarily undermine the country and its principles. But some do, and exist beyond punishment or account.

The potential for evil is certainly there when super-citizens exist above the law. When the New York Times reviewed the book The Crime and Punishment of I.G. Farben, it observed that the story of Farben "Forces one to consider the possibility that when corporate evil reaches a certain status, it simply cannot be defeated."

In the end, the existence of incredibly powerful entities that enjoy the status of citizens demote the vast majority of average citizens to second-class status. If the ideals we hold sacred have any truth to them, if the myths we sleep by have any basis in reality, such a division is intolerable and must be changed. "All men are created equal" once excluded vast swaths of Americans from their basic rights. Battles were fought to change that. Today, a battle to realign the balance of power between the citizen and the super-citizen must also be fought. It must be won.

William Rivers Pitt is a New York Times and internationally bestselling author of two books: War on Iraq: What Team Bush Doesn't Want You to Know and The Greatest Sedition Is Silence. |

| |

|