|

|

|

Editorials | August 2005 Editorials | August 2005

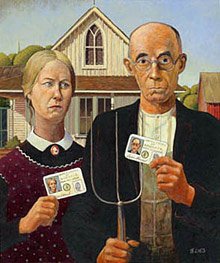

Why the "Real ID" Act, Which Requires National Identity Cards, Is a Real Mess

Anita Ramasastry - FindLaw.com Anita Ramasastry - FindLaw.com

| | More than 600 organizations have expressed their concern over the Real ID Act. |

n May 2005, Congress passed the "Real ID" Act, which requires states - starting in May 2008 - to issue federally approved driver's licenses or identification (ID) cards to those who live and work in the US.

Unlike the USA Patriot Act and other politically sensitive pieces of legislation, Real ID has not made many headlines. Last fall, it was voted down. But then it was reintroduced, and tacked onto the 2005 Emergency Supplemental Appropriations for Defense, the Global War on Terror and Tsunami Relief. (Real ID hence superseded conflicting portions of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004.) Obviously, it would have been a serious political liability for a Congressperson to vote against funding for the war on terror and tsunami relief. So it is unsurprising that there was no debate on, no hearings on, and no public vetting of the Act.

Unsurprising, but disappointing - for hearings might have revealed that Real ID is going to create many headaches and nightmares for state governments, which must now labor under an unfunded mandate; US citizens; and lawful permanent residents alike.

Indeed, as I will explain citizens' privacy will be seriously threatened if the Act is not amended before it takes effect.

No wonder, then, that more than 600 organizations have expressed concern over the Real ID Act. Organizations such as the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, the American Library Association the Association for Computing Machinery, the National Council of State Legislatures, the American Immigration Lawyers Association and the National Governors Association are among them.

What will the Real ID Act Require?

The Real ID Act's identity cards will be required not only if one wants to drive, but also if one seeks to visit a federal government building, collect Social Security, access a federal government service, or use the services of a private entity (such as a bank or an airline) that is required under federal law to verify customer identity.

In other words, it will be well nigh impossible to live without such an ID. That creates not only a huge incentive for citizens and residents to procure IDs, but also a huge incentive for states to comply with this unfunded mandate: If they didn't, their citizens and residents wouldn't be able to get access to any of the services or benefits listed above. Estimates of the cost of compliance range from $80 to $100 million - and states will have no choice but to pay.

In order to get a new approved license - or conform an old one to Real ID - individuals will have to produce several types of documentation. These must prove their name, date of birth, Social Security number, their principal residence (verified by, for instance, a utility bill or lease), and that they are lawfully in the US

Addresses cannot be P.O. boxes. That will predictably cause problems for persons who may fear for their personal safety - including judges, police officers or domestic violence victims - or persons who simply may not have a permanent home, such as the homeless, who may be urgently in need or Medicare or other benefits. There needs to be a procedure to ensure these persons' safety and welfare; currently, the Real ID Act has none.

States will be responsible for verifying these documents. That means that, when it comes to birth certificates and other documents, they probably will have to make numerous, onerous confirming calls to state and municipal officials or companies to verify the documents authenticity. (Paperwork can easily be faked.) In addition, they will have to cross-check Social Security numbers, birthdates, and more against federal databases.

Once created, the IDs must include the information that currently appears on state-issued driver's licenses and non-driver ID cards - name, sex, addresses and driver's license or other ID number, and a photo. (Under the Act, that photo must be digital - for it will be inputted into the multi-state database I will discuss below.) But the IDs must also include additional features that drivers' licenses and non-driver ID cards do not currently incorporate.

For instance, the ID must include features designed to thwart counterfeiting and identity theft. Unfortunately, while including such features may sound appealing, on the whole, these IDs may make our identities less safe.

Once Real ID is in effect, all fifty states' DMVs will share their information in a common database - and may also verify information given to them against various federal databases. In addition, it's very possible that such data will be sold to commercial entities: Some states already allow driver's license data to be sold to third parties.

Even with current, unlinked databases, thieves increasingly have turned their attention to DMVs. Once databases are linked, access to the all-state database may turn out to be a bonanza for identity thieves.

Finally, the IDs must include a "common machine-readable technology" that must meet requirements set out by the Department of Homeland Security. And, somewhat ominously, Homeland Security is permitted to add additional requirements - which could include "biometric identifiers" such as our fingerprints or a retinal scan.

The Risk of Serious Privacy Violations

It's that "machine-readable technology" requirement - along with the possibility of Homeland Security add-ons - that raises the most serious risk that the Real ID Act will cause privacy violations. (The fact that the technology must be "common" also raises the already-high risk of identity theft noted above.)

Many commentators predict that believe radio frequency identification (RFID) tags will be placed in our licenses. (Other alternatives include a magnetic strip or enhanced bar code). In the past, the Department of Homeland Security has indicated it likes the concept of RFID chips.

RFID tags emit radio frequency signals. Significantly, those signals would allow the government to track the movement of our cards (and hence, of us as well).

And not only the government: Private businesses may be able to use remote scanners to read RFID tags too, and add to the digital dossiers they may already be compiling. If different merchants combine their data - you can imagine the sorts of profiles that will develop. An unlike with a grocery store checkout, we may have no idea the scan is even occurring; no telltale beep will alert us.

The State Department - which is going to be use RFID devices in our passports - is including some safeguards, but the Real ID Act requires none. At a minimum, the Real ID Act ought to be amended to ensure that - as will be the case with passports - national IDs have covers that will prevent them from being scanned when closed, and that the data inside will be encrypted so that it cannot be read until and unless it has been swiped and activated through a reader.

How the Real ID Act Ought to Be Amended

As noted above, the Real ID Act ought to include the same privacy measures - encryption, and some sort of metallic covers - that the State Department uses to protect the privacy of passports.

Moreover, as also noted above, the Real ID Act ought to be amended to allow persons in danger to give only a P.O. box address; to accommodate the reality that homeless persons may have neither an address nor a P.O. box.

In addition, Congress should appropriate funding to help the states in what will be a massive compliance effort - rather than leaving them with this expensive, unfunded mandate. Lack of funding will only encourage the states to cut corners, defeating the Act's purpose.

Finally, states should be able to choose to provide licenses to undocumented immigrants. Otherwise, such immigrants may end up driving without licenses or insurance. If they have accidents, their victims will have no recourse. And it's likely they will have accidents - for there will be no reason for them to take driving lessons or tests, since a license will be out of the question.

Anita Ramasastry is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Washington School of Law in Seattle and a Director of the Shidler Center for Law, Commerce & Technology. |

| |

|