A Celebration to Wake the Dead Blends Heritage, Family and Food

Laura Taxel - The Plain Dealer Laura Taxel - The Plain Dealer

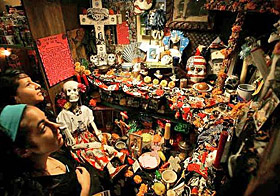

| | Jennifer Ruvalcaba, 14, bottom, and friend Shannie Ortiz, 15, top, check out a community altar at an Olvera Street candle shop. (Brian Vander Brug / LAT) |

In the little town of Chamilpa, outside Cuernavaca, Mexico, where Salvador Gonzales grew up, it's said death comes in threes: at the last breath, at burial, and, saddest of all, when you are forgotten.

To ensure that loved ones are remembered, Mexicans observe El Dia de los Muertos - the Day of the Dead - on Nov. 1 and 2. That holiday honors those who've passed on to another world and welcomes their spirits back for a one-day visit.

It's a joyous occasion and a time for family gatherings. Gonzales, who traces his heritage to the indigenous Mazahua people from the Mexican state of Morelos, usually goes home for Day of the Dead. This year he's staying in Cleveland, where he's lived since 1985. So he decided to organize the city's first Day of the Dead event, which will be held Saturday.

"For most Mexicans this is just a fun date on the calendar, but for people from the countryside who still practice the old ways, it is a sacred time of year," says Gonzalez. "Our celebration on October 29th includes the ritualistic and the playful in the form of traditional foods, music, dance, artwork and a parade."

Originally a harvest festival of ancient pre-Columbian cultures, El Dia de los Muertos is now overlaid with many Christian practices and beliefs connecting it to All Saints and All Souls days.

It's also mistakenly linked with Halloween, because both are in the fall and share the imagery of skeletons and skulls. But they couldn't be more different in their meaning.

"This is a celebration of the natural cycles of life," explains Lourdes Sanchez, who cooks and sells authentic Mexican dishes at the North Union Farmers Market in Shaker Square. "It's not meant to be scary or macabre. When the spirits of dead relatives and friends come to 'see' you, you're glad, not gloomy."

To greet these annual guests, families construct small altars, called oferendas, in their houses, filling them with personal mementos and photos of the deceased - along with their favorite foods and beverages, candles, incense and marigolds.

"If your grandma liked hot chocolate, you put some out for her," says Sanchez. "Mine smoked cigars, so I add those, along with books because my grandparents were readers."

Pan de muerto also goes on the altar. These flavorful breads can be sweet or salty, depending on the region where it's made, but it's their shape that defines them. The simplest are round with crossed bones, pirate-style, on top. More elaborate ones are formed to resemble skulls, skeletons, and even coffins. It's eaten after people come back from the cemetery where they've gone to clean grave sites and repair headstones, as part of a festive meal.

"El Dia de los Muertos is a positive way of relating to the dead," says Rey Galindo, whose family operates numerous Mexican restaurants around town, plus a Latin market, tacqueria and tortilleria in Lorain. "Instead of crying for those who are gone, we're happy because on this day they return to us."

Taxel is a free-lance writer and author of "Cleveland Ethnic Eats, 2005 Edition" (Gray & Co., 2004). She lives in Cleveland Heights. |