|

|

|

Editorials | November 2005 Editorials | November 2005

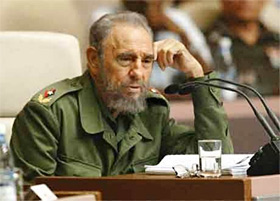

How Should U.S. Prepare for a Post-Castro Cuba?

Warren Richey - Christian Science Monitor Warren Richey - Christian Science Monitor

| | The U.S. government faces a choice on how aggressively it should press for democratic reforms in Havana. |

From the Bay of Pigs to poison cigars, American attempts to rid the world of Fidel Castro have repeatedly been met with embarrassment and failure.

After 46 years, Castro's wheezing revolution has even outlived his cold-war ally, the once-mighty Soviet Union.

Now, amid reports of Castro's fragile health and conflicting expectations about the shape of a post-Castro Cuba, the U.S. government is facing a choice about how aggressively it should press for democratic reforms in Havana after Castro's reign. Top Cuban officials, for their part, are reacting with alarm and bracing for a possible new round of American meddling.

Those in favor of taking bold action - namely, trying to stop Raul Castro from stepping into his brother's shoes - cite post-9/11 concerns that any failing or hostile nation may become a launching pad for terrorists seeking to attack the United States.

Those urging a more restrained approach stress Washington's less-than-impressive record in Cuba. Some point to the deadly insurgency in Iraq two years after what Bush administration officials had assumed would be a quick U.S. military victory.

Many Cuba experts say Iraq and Cuba are completely separate scenarios, noting that political instability in Cuba is unlikely to result in the kind of protracted rebellion under way in Iraq.

But others say the same kind of flawed planning that caused Washington to fixate on Saddam Hussein's removal at the expense of other strategic imperatives is at play in U.S. plans for Cuba after Castro.

"This is the same thinking that has led us astray before, and now in Iraq," says Damian Fernandez, director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University here.

"A policy that is only defined based on the personality of Fidel Castro or [his brother] Raul Castro is misguided," he says. "It blinds us to real concerns that will affect U.S. national interests and the future of Cuba."

White House Plan

The Bush administration has developed a 400-page plan for how to confront the challenges of post-Castro Cuba. In August, it appointed a Cuba "transition coordinator" at the State Department to carry out the plan.

The post-Castro plan addresses everything from water quality to drafting a new constitution to how best to punish Castro's foreign allies. But what has made the plan most controversial is its focus on proactively subverting efforts by Castro to transfer power to his brother, Raul.

"The Castro dictatorship is pursuing every means at its disposal to survive and perpetuate itself through a 'succession strategy,' " the plan says. "U.S. policy must be targeted at undermining this succession strategy."

The plan is consistent with requirements of the 1996 Helms-Burton Act, which bars U.S. assistance to any Cuban government that includes Fidel or Raul Castro. But it carries the requirement one step further by calling for direct action "hastening Cuba's transition" toward democracy.

Some Cuba watchers write off the tough talk in the post-Castro plan as little more than a domestic political tactic. They say it was aimed at shoring up President Bush's flagging support among Cuban-Americans in Miami during last year's presidential election, when the plan was unveiled.

The plan amounts to a statement of goals rather than a blueprint for U.S. action, many analysts say.

"The proposed elements do not add up to 'hastening transition in Cuba,' " says Daniel Erikson, a Cuba expert at Inter-American Dialogue in Washington.

"The reality is the United States does not know that much about how to build democracy in the developing world," he says.

Others see the plan as a useful means of maintaining political pressure on the Castro regime while sending signals of encouragement to regime opponents and dissidents on the island.

"From Franco [in Spain], to Duvalier [in Haiti], to Somoza [in Nicaragua], to the communists in East Germany, they all had a succession strategy. They all thought somebody from their party would continue in power. But that hasn't happened," says Frank Calzon of the Center for a Free Cuba in Washington. "I'm sure Cuba is not going to be an exception to that worldwide rejection of dictatorship."

No Immediate Change After Fidel?

Nonetheless, most Cuba experts doubt Castro's death will bring an immediate transition toward more democratic government. Instead, they say, Raul Castro is most likely to follow his brother as the next leader of Cuba.

"There are a few academics out there who assert that inevitably the reformers will win the post-Fidel struggle. I don't think so," says Juan del Aguila, a political scientist and Cuba expert at Emory University in Atlanta. "There is no reformist political faction in evidence now."

Any would-be reformers among Cuba's top officials who call for liberal democracy would be purged, he says. "They would immediately become nonpersons."

Brian Latell, a retired Cuba expert at the Central Intelligence Agency, agrees that Raul Castro will probably emerge as Cuba's new leader. He makes the point in his new book, "After Fidel: The Inside Story of Castro's Regime and Cuba's Next Leader."

But Latell says Raul Castro will not have the free hand that his brother has enjoyed in defending the revolution at the expense of the Cuban people.

"After Raul takes over there will be a very, very widespread and deeply based pent-up demand for change - for political, social, and economic decompression," Latell says. "I think Raul is going to have to deal with that. Those are going to be among his gravest challenges."

Such pressures alone won't be enough to force democratic reforms, Latell says.

"My guess is that [Raul] is going to adopt a Chinese model, remaining tough politically - no democracy, no opposition parties - but [pushing for] a fairly wide economic opening," he says.

"Of course it is a slippery slope," the retired intelligence officer says. Raul Castro "knows what happened in the Soviet Union, so he's going to have to be very careful." |

| |

|