|

|

|

Health & Beauty | November 2005 Health & Beauty | November 2005

Competition Freaks

Marianne Szegedy-Maszak - LATimes Marianne Szegedy-Maszak - LATimes

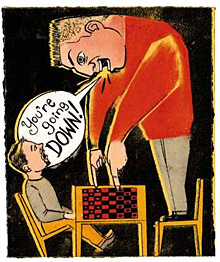

| | THE NEED TO WIN: You know them, those people who just have to win. Now scientists are finding out what's behind the drive - motivation, control, evolution - and are trying to help. (Edel Rodriguez / LATimes) |

"Winning isn't everything," Vince Lombardi famously said. "It's the only thing."

For a particular group of competitors, Lombardi's one-liner is less a wry comment on cutthroat athletic competition than a simple fact of life. In boardrooms and bedrooms, in playing fields and universities, the hyper-competitive person appears transforming even the most trivial transaction into a ruthless face-off with a winner and a loser.

We know it when we see it. The squash champion father who introduces his 12-year-old son to the game by beating him 15 to 0, three games in a row. The ruthless queen bee who dominates her social group with cattiness and designer everything. The out-of-control soccer mom berating the referee from the sidelines; the husband banned from playing family board games because he ruins the game when he wins and ruins the entire evening when he loses.

Today, a broad array of recent psychological research has led some researchers to conclude that hypercompetitiveness resembles a diagnosable mental disorder a volatile alchemy of obsessive compulsiveness, narcissism, neurosis and sometimes a dose of paranoia.

Psychologists have even linked the hypercompetitive personality to such seemingly disparate conditions and behaviors as road rage, drunk driving, eating disorders, addiction and depression.

It's a style and temperament that affects all other relationships and which, over time, becomes fundamentally impairing, causing fractured families, social isolation and even the disintegration of careers.

Psychologists, therapists and psychiatrists are examining the forces that may create these personalities, and trying to figure out ways to better help them.

Such win-at-all-costs behavior may be unsettling but, truth be told, it's not so very far from what our culture views as laudable.

"We define the American dream as people pulling themselves up by their bootstraps," says Steven Eickelberg, a Paradise Valley, Ariz., psychiatrist who specializes in the psychology of high-performance competitors and whose clients include high-profile athletes and business executives. "But how many people do we walk over to be successful? When is this kind of competition admirable, and when is it pathological?"

Nearly every day a story appears about a hypercompetitor dragging a company, or a team, or simply himself into a terrible mess.

Only this month, Philadelphia Eagles wide receiver Terrell Owens was benched despite his magnificent performance while injured in the Super Bowl. Too many other times, his behavior was characterized by belligerence and vocal demands for attention. Owens recently complained that he didn't receive sufficient recognition for his 100th career touchdown reception during a game against the San Diego Chargers on Oct. 23. And when he thought that other players had been talking about him behind his back, he stormed into the locker room and challenged them to a fight.

In fact, the pantheon of the hypercompetitive in American sports and business is littered with examples of bad behavior. In 1978, Oakland Raiders defensive back Jack Tatum, nicknamed "the assassin," hit another player so hard he became a quadriplegic. He not only didn't apologize but justified his action saying, "It was a clean hit."

Then there's Albert J. Dunlap, a notorious chief executive who referred to himself as "Rambo in pinstripes." Dunlap's Agent Orange management style which earned him the nickname "Chainsaw Al" involved firing thousands of employees, demeaning anyone who disagreed with him and plowing through the company's assets. His actions helped bring Sunbeam Corp., which he took over in 1996, from a $1-billion company to Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

At the core of every massive corporate unraveling, whether it is Sunbeam, Enron or the Helmsley Hotels, sits a hypercompetitive manager or CEO, says Barbara Kellerman, research director for the Center for Public Leadership at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government and author of the 2004 book "Bad Leadership: What It Is, How It Happens, Why It Matters."

"At a minimum, those whose competitiveness makes their reach exceed their grasp are ineffective and unethical; at a maximum they are downright detrimental to society," Kellerman says.

Even without such public wreckage, there is something unsettling, even alienating, about the person who just can't seem to turn it off for whom a game of Candyland with the kids is played with the same intensity as a championship tennis match.

Hypercompetitiveness may be behaviorally inevitable, says UCLA evolutionary biologist Jay Phelan. That's because some degree of competitiveness is a very human trait. "We are built for always wanting to do a little bit better and accumulate more," says Phelan, coauthor of the 2000 book "Mean Genes: From Sex to Money to Food, Taming Our Primal Instincts." As humans, we have evolved to be competitive, he says. But some people are at the extreme end of the spectrum and compete to extremes.

Because the world today is so much more complex, Phelan says, we have myriad more ways to compete when we drive, shop and work and through the clothes we wear, the houses we buy, even the friends we have.

But there's a difference in degree and tone between being competitive and hypercompetitive one that clinicians believe may be rooted in questions of motivation, self-control and self-worth.

Driving Forces

Psychologists have long understood that the source of motivation for everyone athletes, dieters, you name it can be rooted in either an internal quest for excellence or an external motivator such as a trophy, money or fawning recognition from others.

Internally motivated people are less likely to be hypercompetitive. They lack that constant push for recognition.

In contrast, studies suggest that external motivation is central to the hypercompetitive psyche.

A 2003 study of 319 young athletes in Texas underscores the influence of these inner and outer types of motivation. Published in the Journal of Psychology, it tried to predict from questionnaires whether an athlete would be a good sport, a graceful loser, a good team player, and someone eager to learn from mistakes and losses rather than acting defensively or angrily.

The researchers found that sportsmanship didn't relate to what the sport or activity was, or even how intensely competitive the event might be. What mattered were qualities associated with internal motivation such as enhanced self-esteem and a desire not to win but to master the task.

In contrast, the athletes who said in a questionnaire that they participated in sports for external rewards such as social status and beating a competitor also scored as less sportsmanlike. They were also far less effectively competitive, losing focus and lacking internal self-discipline.

Those who are externally motivated often think "their self-worth is contingent on winning," says John Tauer, a professor of psychology at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn., who has studied achievement and internal motivation. "When they start any activity, their first thought is, 'I need to win.' "

Motivation isn't the only thing that shapes a pathological competitor. Another noxious ingredient may be needed, according to a study published in the Journal of Personality Assessment in 1997. Richard Ryckman, a psychologist from the University of Maine, and coauthors conducted psychological surveys of hypercompetitive and healthily competitive undergraduates.

They found that both groups scored high on measures of achievement and striving for an exciting, challenging life. The answers of the hypercompetitive people, however, indicated that they valued "power and control over others." Their responses, unlike those of the healthy competitors, also exhibited lack of care and respect for others.

"The gist of this kind of competition is self-aggrandizement at the expense of others," Ryckman says.

Contrast this with the mind-set of world-class competitor Lea Antonopolis-Inouye, now a financial planner in Huntington Beach, who played professional tennis from 1977 to 1988. In 1977, she was the junior Wimbledon champion. She played Wimbledon for the next 10 years, and competed in the U.S. Open and the French Open.

As a head tennis pro at a private tennis club for two years, Antonopolis-Inouye says, she was confronted day after day with an abundance of noxious competitiveness. People jockeying for particular courts and trainers. Erasing names from the roster of practice courts and replacing them with others.

She recalls one man at a tournament loudly demanding a forfeit because another team was 15 minutes late for a match. After a relentless half-hour, Antonopolis-Inouye gave his team the win he wanted.

Yet, she says, real victory, the one that she tasted on the Center Court in Wimbledon as a junior, "is a by-product of super-hard work and dedication and being driven to perfection

. You can't just win. You have to forget about winning and work on other things."

On the professional tennis circuit, Antonopolis-Inouye befriended such stars as Chris Evert and Steffi Graf, and observed that their competitive greatness was not predicated on a simple need to win or a fiercely competitive nature. Their goal, instead, was to achieve perfection of play and execution for themselves.

"The most successful athletes that I have known have absolutely no irrational competitiveness," she says.

Antonopolis-Inouye is speaking a foreign emotional language for the hypercompetitive person. After all, there is no doubt that being hypercompetitive often pays and sometimes handsomely. Those punctual tennis players at the private club notched a win on their rosters. Former Tyco International CEO L. Dennis Kozlowski, superstar athlete Michael Jordan, even the imperious hotelier Leona Helmsley all have been held up as examples of hypercompetition by those who study the trait, and all reached stratospheric heights of money and influence. (Until, for Kozlowski and Helmsley, the fall came.)

"The take-no-prisoners competitors can be very successful much more rapidly than win-win competitors, mainly because they are obsessed, single-track and totally focused on their own desired result," says Denis Waitley, former chairman of psychology for the U.S. Olympic Committee's Sports Medicine Council and president of the Waitley Institute in Rancho Santa Fe.

Why's it so bad for people, then?

"The problem? This obsession on winning and beating the competition becomes a reflex habit," Waitley says.

That reflex is extremely difficult to control. Stuart Krohn, coach for the Santa Monica Rugby Club, recalls of his former hypercompetitiveness that "everything was a battleground a ping-pong table, a conversation. I could feel the blood start to rush, and I could feel myself reacting to something that I shouldn't have reacted to." Even as a kid, he says, "it was all about winning."

Krohn's competitive nature did reap returns. He played rugby internationally for decades, winning two world championships. Now 43, he led the Santa Monica club to win, last season, its first national championship in more than 20 years.

But, he says, he also had to win every argument with his girlfriend, turned conversations at dinner parties into intense competitions, and nurtured a rage and hatred for other teams and referees that was sometimes overwhelming.

Relationship troubles

Hypercompetitive people typically may succeed in many parts of their lives, but interpersonal, especially intimate, relations are often deeply troubled, says psychiatrist Eickelberg. A 2002 study in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology examined romantic relationships of hypercompetitive people and found these people "reported lower levels of honest communication with the partner, greater infliction of pain on him or her, stronger feelings of possessiveness, higher levels of mistrust, stronger needs to control their partner, lower ability to take their perspective, and higher levels of conflict."

Despite this list of problems, hypercompetitors tend to lack both insight and empathy and rarely enter the door unless a crisis or an ultimatum shoves them through it, psychologists say. It typically happens in middle age. Many, Eickelberg says, enter his office and announce, "My wife said I had to come."

Others see enormous successes and achievements interrupted by jarring moments of reckoning: burnout, depression, divorce, a rift with a child, hitting a wall. A wake-up call eventually intrudes on the self-absorbed drive to win.

Clinicians who work with hypercompetitive individuals say treatment is a long, hard, therapeutic slog. When winning has been paramount for one's entire life, the therapeutic dialogue is likely to be characterized by anger, challenges and endless jockeying for dominance with the therapist. The very dynamics that a spouse or partner in life found intolerable are in florid display in a therapeutic setting.

The empathy gulf can be huge. Eickelberg sometimes asks his patients to figure out what a spouse is thinking or feeling. "I often get the response, 'I drew a blank' or 'I think she was doing good.'

Gradually you see that these are people who probably lack a healthy capacity to understand other people. And that is where you begin."

Slowly, through a combination of good old-fashioned talk and behavioral therapy, a transformation can gradually take place. A hypercompetitor decides to volunteer in a school for disadvantaged kids, or devotes less time to the office, or reaches out to a spouse or a child in ways that were impossible before.

This is not to say that all hypercompetitors will always come to some moment of truth. Kellerman, of the Center for Public Leadership, says: "There is no inevitability that these people have to fall in some way. We know that for every person who is caught, or who faces some great trauma in their lives, there are scores of others who don't."

Life did change for Krohn in his 35th year. His girlfriend dumped him, he says, because he was so intensely competitive with her. Then another thing happened that opened his eyes: A younger, less-experienced teammate was badly injured in a scrum. Only miraculous medical care prevented him from becoming a quadriplegic.

Krohn visited his teammate in the ICU every day. "This guy was

fighting for his life, and I sat there with a lot of time to think," he recalls. "I finally realized that this is a game. I realized that everybody is not against me and life is not a full-time competitive arena."

Krohn hasn't turned into a pussycat: He's still a "yeller" at practice and on the sidelines. Team members say he pushes players sometimes to the breaking point. But he has now been happily married for two years and says he approaches competition in a very different way today than he did eight years ago.

In addition to coaching the Santa Monica rugby team, he is one of the founding teachers, and of course rugby coach, at View Park Prep Charter School in the Crenshaw district. He says with some pride that they haven't won a game in three years and they attract the kids who aren't doing other sports. "When I'm coaching the kids, I don't focus on winning above their character and their attitude toward the sport," he says. "They have to get that right first."

He pauses briefly. "I didn't get that when I was a kid." |

| |

|