|

|

|

Editorials | January 2006 Editorials | January 2006

On the Subject of Leaks

New York Times New York Times

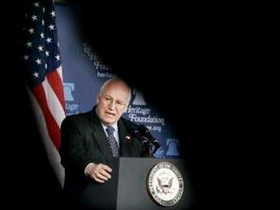

| | U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney delivers a speech on the war in Iraq in Washington January 4, 2006. Cheney on Wednesday strongly defended a secret domestic eavesdropping operation and said had it been in place before the September 11 attacks the Pentagon might have been spared. (Reuters/Jim Young) |

Given the Bush administration's appetite for leak investigations (three are under way), this seems a good moment to try to clear away the fog around this issue.

A democratic society cannot long survive if whistle-blowers are criminally punished for revealing what those in power don't want the public to know - especially if it's unethical, illegal or unconstitutional behavior by top officials. Reporters need to be able to protect these sources, regardless of whether the sources are motivated by policy disputes or nagging consciences. This is doubly important with an administration as dedicated as this one is to extreme secrecy.

The longest-running of the leak cases involves Valerie Wilson, a covert CIA operative whose identity was leaked to the columnist Robert Novak. The question there was whether the White House was using this information in an attempt to silence Mrs. Wilson's husband, a critic of the Iraq invasion, and in doing so violated a federal law against unmasking a covert operative. There is a world of difference between that case and a current one in which the administration is trying to find the sources of a New York Times report that President Bush secretly authorized spying on American citizens without warrants.

The spying report was a classic attempt to give the public information it deserves to have. The Valerie Wilson case began with a cynical effort by the administration to deflect public attention from hyped prewar intelligence on Iraq. The leak inquiry in that case ended up targeting the press, and led to the jailing of a Times reporter.

When the government does not want the public to know what it is doing, it often cites national security as the reason for secrecy. The nation's safety is obviously a most serious issue, but that very fact has caused this administration and many others to use it as a catchall for any matter it wants to keep secret, even if the underlying reason for the secrecy is to prevent embarrassment to the White House. The White House has yet to show that national security was harmed by the report on electronic spying, which did not reveal the existence of such surveillance - only how it was being done in a way that seems outside the law.

Leak investigations are often designed to distract the public from the real issues by blaming the messenger. Take the third leak inquiry, into a Washington Post report on secret overseas CIA camps where prisoners are tortured or shipped to other countries for torture. The administration said the reporting had damaged America's image. Actually, the secret detentions and torture did that.

Illegal spying and torture need to be investigated, not whistle-blowers and newspapers. |

| |

|