|

|

|

Editorials | February 2006 Editorials | February 2006

Mexico's Burden

Sergio Muñoz - LATimes Sergio Muñoz - LATimes

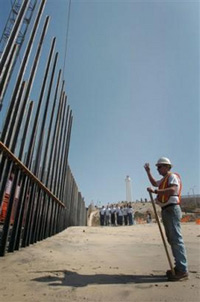

| | A U.S. construction worker signals to a crane operator during re-construction of the U.S.-Mexico border wall as Mexican federal congress members (in the background) watch on in Tijuana, Mexico. (AP/David Maung) |

As a Mexican, I'm outraged that politicians in Washington believe it is necessary to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border to keep my compatriots from coming here to work. But I'm also ashamed that Mexico is, in many ways, to blame for making the border fence possible.

Mexico's failure to understand the immigration debate in the U.S. has weakened its negotiating position. Mexican President Vicente Fox is not entirely at fault. Illegal immigration is a controversial issue in Mexico as well, and his political maneuvering room is limited. When he formally protested to the U.S. State Department about the House-passed legislation calling for a 700-mile border fence, some politicians still accused him of timidity and demanded that he had to stop its construction. During a recent presidential campaign speech, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the candidate of the leftist Democratic Revolution Party, even accused him of lacking the moral stature to stand up to the U.S.

Although the migration of Mexicans to the United States has been a constant for more than a century, Mexico's politicians have failed to articulate a coherent and realistic national immigration policy because the country's political parties and institutions, its business sector, academics, media and public do not all agree that illegal immigration is a bad thing. Paradoxically, Mexico's budding democracy has made it harder to achieve such a consensus because its political parties have greater parity than when the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, enjoyed a political monopoly.

Still, the Fox administration has failed to adequately inform Americans about the myriad successes of its border cooperation with U.S. authorities. For instance, few know about the two countries' exchanges of intelligence and information to ensure that the busy, 2,000-mile-long border doesn't become a conduit for terrorists seeking to enter the U.S. Four and a half years after 9/11, no terrorist threat has been connected to a southern border crossing. That's an amazing achievement considering there are about 1 million legal crossings a year, and that every day more than 300,000 vehicles crisscross the 53 points of entry into the U.S., carrying about $650 million worth of merchandise.

As an American, I want to believe that the Senate, when it takes up the immigration legislation next month, will not only strip the fence from the bill but also its other mean-spirited provisions. I'm panicked by the thought that I would be classified as an "alien smuggler" if caught driving a nanny or a gardener who, unbeknownst to me, was living here illegally. Another provision would make it possible to jail all of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in this country by making their unlawful presence an "aggravated felony" rather than a civil violation. And a provision that would turn state and local police into immigration agents would only seed confusion in the nation's barrios.

How radical is this approach to illegal immigration? Well, the likes of Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez, certainly no friends of Fox, have held up the House immigration bill as a prime example of how el imperialismo yanqui disrespects even its closest allies.

I know that extending the border fence, begun in the mid-1980s, from California to the tip of Texas won't fix this nation's broken immigration system. The unprecedented rise of illegal crossings in the late 1980s and the '90s has come despite greater border fortifications and a dramatic increase in the Border Patrol.

I also realize that Mexico must understand the new realities of the post-9/11 world and should take control of its side of the border. To do that, it must finish its economic reforms so that the economy can grow at sustained rates to generate enough good jobs to keep Mexicans at home. It also must change its laws and regulations, including perhaps the constitution, to require Mexicans who want to emigrate to obtain proper legal documentation before doing so. As it now reads, no law bars a Mexican from simply walking across a border.

Not too long ago, most American ninth-graders knew by heart a Robert Frost poem that challenged the traditional idea that good fences make good neighbors.

Before I built a wall I'd ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That wants it down.

Humiliation doesn't foster cooperation and understanding between friends struggling with such a complex problem as immigration. The wall, if built, would unnecessarily humiliate Mexicans. It should humiliate Americans as well.

Sergio Muñoz is a LATimes editorial writer and a citizen of both Mexico and the United States. |

| |

|