|

|

|

Editorials | Environmental | February 2006 Editorials | Environmental | February 2006

Tijuana Sprawl Cuts into Key Ecosystem

Sandra Dibble & Mike Lee - San Diego Union-Tribune Sandra Dibble & Mike Lee - San Diego Union-Tribune

| | Miguel Angel Vargas (right) and Fernando Ochoa of the Pronatura conservation group are working to preserve land between Tijuana and Tecate. (K.C. Alfred/Union-Tribune) |

Tijuana – Every day, bulldozers push Tijuana's perimeter farther east, carving up hillsides and gobbling vacant parcels. Piece by piece, critical wildlife pathways that cross into San Diego County are lost.

As development surges in Tijuana, lizards and butterflies, coyotes and mountain lions increasingly must share one of the world's biological hot spots with industrial parks and a growing population.

Saving the wildlife corridors is key to maintaining a rich ecosystem, according to an emerging cross-border coalition pushing for government regulation, land purchases and conservation easements to protect key properties from development.

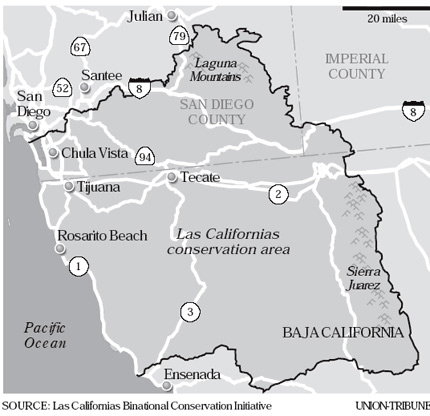

While similar projects are popping up worldwide, the Las Californias Binational Conservation Initiative is the first of its kind along the California-Mexico border.

The pathways enable species to travel to habitats on both sides of the border.

“If you cut off an artery you can die, and that's what is going to happen here,” said Miguel Angel Vargas, a land conservation specialist with Pronatura, Mexico's oldest and largest conservation group.

Las Californias is powered by some of the continent's major environmental groups. They want to preserve corridors in an area that spans four major watersheds – Sweetwater, Otay, Tijuana and Guadalupe – and covers more than 2.5 million acres.

About two-thirds of the land is in Mexico.

The Nature Conservancy acquired two small plots near Campo in December, supplementing an already vast network of publicly protected lands in San Diego County.

But without aggressive action in Mexico, Tijuana's sprawl threatens to reduce the ecological value of tens of thousands of acres of open space north of the border.

Conservationists face numerous hurdles in Mexico because of overlapping property titles, lack of government resources and the rapid pace of growth. Simply identifying potential preservation sites has been a painstaking process. Finding funding has been challenging, too.

“We are lagging behind,” Vargas said. “Private land conservation in the U.S. is 50 years old, and here in this region it started barely four years ago. We're still in diapers.”

The coalition also faces obstacles in the United States. For instance, a proposed border security fence being considered by Congress would slice sections of the Las Californias ecosystem in half.

But the initiative does have significant support.

On the U.S. side, backing has come from The Nature Conservancy – the largest environmental group in the world – and the Oregon-based Conservation Biology Institute.

Pronatura has done the bulk of the work in that country, collaborating with Tijuana's Municipal Planning Institute to identify potential conservation areas.

Promoters of the idea include the San Diego-based International Community Foundation, which has funded Pronatura's initial land studies.

The effort has also gained the ear of the San Diego Association of Governments, which consults the Las Californias blueprint as it develops border-growth plans.

Another key supporter has been Rancho La Puerta, a spa outside Tecate. In 2003, the spa's owners made 2,000 acres of their property off-limits to development under a conservation easement monitored by Pronatura. The easement was a first for Mexico's northern border.

Expanded efforts

The first international conservation arrangement was formalized more than 70 years ago in the Rocky Mountains, where Glacier National Park in Montana connects to the Waterton Lakes National Park in Canada.

Now called a “peace park,” Glacier-Waterton is still touted as a model for how countries can work together on preservation.

Today, 112 nations share environmentally protected lands with their neighbors, according to the newly published book “Transboundary Conservation.”

“(These) areas are being established on an unprecedented new scale,” Peter Seligmann, chairman and CEO of Conservation International, said in the book.

Like other boosters, Seligmann touts the potential for shared habitat to improve relations between countries, especially where national borders are disputed. Supporters also said such agreements can be profitable by luring nature-loving tourists.

But the alliances are sometimes complicated by countries' widely differing resources and perspectives on conservation.

The disparity is easy to see in the target area for Las Californias.

North of the border, nearly 400,000 acres have been designated as open space. On the Mexican side, the total is 14,000 acres.

Pronatura has focused on a 25,000-acre area straddling Tijuana and its eastern neighbor Tecate where development is rapidly eating up vacant lands.

One warm winter morning, Vargas and Fernando Ochoa, also from Pronatura's land conservation office, stood outside a cluster of tightly packed row houses in eastern Tijuana.

The scene hardly evoked a global conservation hot spot: walls covered with graffiti, shantytowns with rusting cars in the distance, a new highway that foreshadows more development.

But a few miles away on the banks of the Tecate River, birds sang as the wind swept through cypress trees. Farther west, cars lined up at the toll station right beneath a mesa that remains important habitat for the endangered quino checkerspot butterly.

“You mention Tijuana and Tecate, and people think of maquiladoras, industry, growth,” Ochoa said. “The common conception is that the habitat is totally destroyed.”

Hurdles abound

Pronatura's first step was to identify what open space still exists. Working with San Diego State University and the city of Tijuana, Pronatura has developed maps of the region. These maps show characteristics such as land costs, land use and areas with the greatest conservation possibilities.

Through its surveys, Pronatura saw how the uncertainty of Mexican land ownership is a major hurdle, because it makes it hard for conservation groups to target potential collaborators.

While much of the land on the U.S. side is publicly owned, most of the Las Californias property in Mexico is split into numerous private parcels. Many plots have been bought and sold without being publicly recorded, so ownership is often unclear and boundary disputes abound.

Another problem is the high cost of land, and speculation in the Tijuana-Tecate corridor. For instance, the construction of a Toyota plant in an eastern Tijuana region known as El Gandul sent industrial land prices in the surrounding area skyrocketing.

Land-use plans for Tijuana and Tecate designate conservation areas. But without legal safeguards in place, these can be converted to residential or industrial use.

“The problem in Mexico, not just Tijuana, is that we have not developed the mechanisms so that these lands remain untouched,” said Ana Elena Espinoza López, head of Tijuana's Municipal Planning Institute. “Just because I say, 'This is a conservation area,' is not enough.”

Hoping for momentum

While Mexico struggles to establish conservation tools, the first signs of Las Californias progress in the United States are sprouting near Campo.

The Nature Conservancy and its partners have sewn up two land deals next to a Navy SEALs training outpost.

At about 330 acres, the rugged and remote properties aren't large by conservancy standards, but they have taken on statewide significance.

This is partly because they help link parcels of undeveloped public land near where a canyon creates a corridor for animals such as deer and snakes to avoid Interstate 8 traffic.

The land deals inspire confidence among Las Californias organizers for what they hope will be a series of similar moves on both sides of the border.

“It . . . gives us some tangible results,” said Cam Tredennick, a project director in the San Diego office. “(When) you are able to do one transaction, people see that it really can happen.”

But even in the United States, the future of Las Californias remains uncertain in light of legislation passed by the U.S. House of Representatives to build 700 miles of new border fences to keep out illegal immigrants.

U.S. Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-Alpine, called for the barriers – which include about 20 miles of fencing near Tecate – to be located to the southwest of the newly purchased Los Californias parcels.

A Hunter spokesman acknowledged the concerns about fences limiting wildlife movement, but he said national security concerns supersede species' needs.

Las Californias backers aim to convince politicians that unfenced habitat provides a good buffer between the countries because it keeps homes, roads and people away from the border.

Pronatura's Ochoa remains resolute in the face of challenges. He hopes that someday Las Californias will move ahead with funding and broad public support. “There will come a moment in which attention will be here,” Ochoa said. “We have to be prepared.”

Sandra Dibble: (619) 293-1716; sandra.dibble@uniontrib.com Mike Lee: (619) 542-4570; mike.lee@uniontrib.com

|

| |

|