|

|

|

Editorials | Environmental | April 2006 Editorials | Environmental | April 2006

Mexico Dam Faces Growing Radical Opposition

Mark Stevenson - Associated Press Mark Stevenson - Associated Press

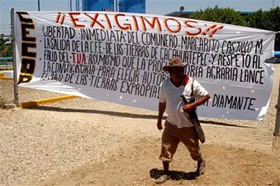

| | A Mexican farmer from the state of Guerrero walks past a banner covering the entrance to a water facility near Acapulco, Mexico, Tuesday, April 4, 2006. About 100 radical farmers seized a pumping plant that supplies about 70 percent of Acapulco's water on Tuesday to protest government plans to build a US$1 billion hydroelectric dam. (AP Photo/Gonzalo Perez) |

La Garrapata, Mexico – Hundreds of machete-wielding farmers opposed to a hydroelectric dam project briefly seized a pumping plant, cutting off much of the water supply to Acapulco just days before tourists flock to the Pacific resort for their Easter vacations.

The protesters ended a two-day blockade of water from the Papagayo River late Wednesday that had threatened to plunge the city of 1 million into a crisis. They vowed, however, to continue fighting government plans for the $1 billion dam on the waterway.

“We wanted the people of Acapulco to see what it's like to go without water for two days, three days or more,” said protest leader Marco Suastegui, referring to the water shortages that protesters fear will dry up their farms and fisheries if the dam is built.

Authorities say the dam is needed to supply already water-starved Acapulco for the next 50 years. Protesters maintain the project will benefit only tourist resorts.

Officials fear such radical opposition movements are gathering strength throughout Mexico, and could block infrastructure projects for decades to come.

Water shortages resulting from the protest were reported among the 80,000 residents of slums that hug the mountainsides in Acapulco, 20 miles from the proposed dam. Richer neighborhoods were saved because they had a two-day supply of water stored in local distribution tanks, and tourists were unaffected because the protesters didn't seize pumps serving the hotel zone.

The resort is one of Mexico's top vacation spots and the region's top source of income. It is expected to nearly double in population over the next 15 years.

Though the protesters handed the pumping station back over to authorities in exchange for compensation payments for some land and the release of one of their colleagues, neither side shows signs of yielding. Bloodshed has already occurred with two deaths that residents believe are linked to the dam dispute.

“We are ready to give our lives to defend our land,” said Facundo Hernandez, a farmer from the hamlet of Salsipuedes who participated in the water-plant takeover. “This area will become like desert if they build the dam,” he predicted.

Acapulco Mayor Felix Salgado complained of the protesters, “a few people cannot hold Acapulco hostage.”

The protesters appear to be a minority, even among those affected by the dam project. They say they are advised and inspired by radicals who kidnapped officials, tied them to a hijacked tanker truck and threatened to blow it up in 2002 to stop a proposed airport project on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Those protesters demonstrated again Thursday, blocking roads and holding five officials hostage, and now some in the government fear the spread of such radical opposition movements could pose problems for other projects.

“That is the fear,” said Umberto Marengo, the project coordinator of the dam project for the Federal Electricity Commission. “Any project that the federal government wants to do could be blocked by opponents with machetes. That would be a terrible situation.”

Indeed, another dam project in the western state of Jalisco has been delayed for years by opponents. Opposition has spread even to wind-power projects and leftist rebel groups have championed the cause.

Inhabitants of the area to be flooded by the dam – 3,000 people in total – would be paid $1,900 an acre for their land, given new homes and be permitted to live on the edge of the newly created lake, which officials say would be ideal for fishing and tourism. Many have accepted the deal.

Government officials acknowledge the river level will be low for about 1˝ years as the dam fills, but they promise to guarantee a minimum flow in the interim and higher-than-average water levels in following years.

But opponents say it's not a question of price, but of defending their way of life: fishing in the Papagayo and growing bananas, mangoes and other fruits on land their grandfathers farmed.

“People are ready. They're not going to back down. I think there are going to be deaths,” said Francisco Hernandez Valeriano, 65, whose town, Aguascalientes, lies about 10 miles downstream from the dam.

“We are going to defend our land just like they did in Atenco,” said Juan Garcia Valente, 44, referring to the 2002 airport protest. Both men fear the dam will cut off or reduce the flow of the river, threatening their riverside farms and fishing grounds. They also worry about the danger of living downstream if such a huge dam were to break.

Bricklayer Fortino Carmona, 26, supports the dam. He hopes it will bring jobs in tourism or construction but acknowledges the fight has turned ideological, and possibly bloody.

“There is a potential for violence,” Carmona said, describing opponents as people who “remain stuck in the past.”

Residents from 19 towns voted in favor of the project. The bulk of the opposition comes from downstream villagers who aren't eligible for compensation payments, and officials now concede they may have to consider payments of some kind to them. |

| |

|