|

|

|

Editorials | May 2006 Editorials | May 2006

The Flipside of Immigrant Dreams: Broken Families

Adriana Garcia - Reuters Adriana Garcia - Reuters

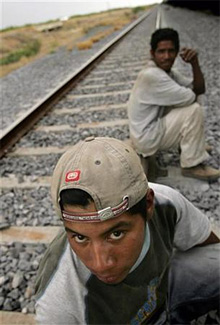

| | Young men rest on a railway track as they travel to the border city of Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, hoping to cross into the US. (Reuters/Carlos Barria) |

For illegal immigrants in the United States, the flip side of the American dream is that mothers, fathers and children are split up across borders - often for years.

With no documents that would allow them to leave the United States to visit their relatives and salaries that start at $5 per hour, they find it almost impossible to return home.

The immigration-overhaul bill in the Senate could give those families a chance to reunite. If approved, the law would offer a path to U.S. citizenship for millions of illegal immigrants - and the chance to obtain legal travel papers.

It would give hope to Adolfo Gonzalez, a 36-year-old construction worker from El Salvador. The last time he saw his only son was 13 years ago, when the boy was 2.

Gonzalez's wife joined him in Maryland, also illegally, nine years ago. But they decided the 22-day trip through Mexico into Arizona would be too dangerous for their child. So the boy stayed with his grandparents in El Salvador.

"One suffers so much to leave a child behind. I always keep thinking of coming back, but my brothers tell me to stay, because life is very hard there," said Gonzalez, who sends $350 a month to his family, hoping his son will one day attend college.

More than half the 11 million illegal immigrants living in the United States in 2005 were women or children, according to a report by the Pew Hispanic Center in Washington

Up to 35 percent were women and 16 percent - nearly 2 million - were children who arrived in the United States with parents or alone, according to the report.

There were 3.1 million children who are U.S. citizens by birth living with families in which the family head or spouse was an illegal immigrant, the March report said.

LEAVING CHILDREN BEHIND

Many of the women who immigrated were single mothers who left their children back home, said Pulitzer Prize winner Sonia Nazario, a Los Angeles Times journalist and author of a book titled "Enrique's Journey."

It is the true story of a Honduran boy who traveled to the United States to search for his mother, who left when he was 5 years old. The author made the same trip as the teenage boy, trekking up the length of Mexico clinging to freight trains.

She wrote the book after talking to a Guatemalan woman who cleaned her house and had left her four children.

"This situation is very common. In Los Angeles, four out of five women that work as nannies have their own children back in their countries," Nazario said.

Some who cross the border into the United States are sure they will be able to feed their children. Others end up having children in the United States and that heightens their fear of deportation.

"Deportation is another way to split families," said activist Emma Lozano, from Centro Sin Fronteras, a community center that helps families facing deportation in Chicago.

She wants wider immigration legislation to forgive immigrants threatened with deportation for working without documents, or with false ones.

"We need a moratorium from President George W. Bush, so that those families can be reunited," Lozano said.

That is exactly what Mexican Elvira Arellano, 31, a single mother of a 2-year-old American son, needs. She was caught working with a false Social Security number and now faces criminal charges and deportation.

In April, Arellano was one of 1,187 people seized in April in an Immigration and Customs Enforcement raid in 26 states. She was working at a factory in Chicago.

On hunger strike since May 10, Arellano will soon find out whether a court will order her deportation. She does not want to leave her son behind, but she also wants him to have a better future in the United States.

"I have to think what is best for my son. As an American citizen I think he has the right to have his mother next to him," she said. "That's what I am fighting for." |

| |

|