|

|

|

Editorials | June 2006 Editorials | June 2006

The Populist at the Border

David Rieff - NYTimes David Rieff - NYTimes

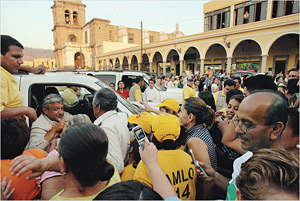

| | Andrés Manuel López Obrador greeting the hopeful after a speech in Jalisco. (Lynsey Addario-Corbis/NYTimes) |

In the richer neighborhoods of Mexico City, armored S.U.V.'s and sedans have become almost commonplace. A decade ago, the only people driving around the city in armored passenger cars were members of Mexico's established business oligarchy — families like the Slims and the Azcárragas, who have long played a leading role in the country's politics as well as its economy. But now the custom has percolated down from the superrich to the merely well heeled. And with good reason: in recent years Mexico's sprawling capital has become one of the most dangerous cities in the world for the poor and the prosperous alike. "People here lead gated lives" was the way one acquaintance recently put it to me.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who was the mayor of Mexico City from 2000 to 2005 during the great upward spike in crime, is now running in next month's elections as the presidential candidate of the left-wing P.R.D. (Party of the Democratic Revolution). Yet the city's problems — the increasing dereliction of its physical infrastructure as well as the deterioration of personal security — seem to have done nothing to dent his enormous popularity among residents of Mexico City and, more widely, among Mexico's poor. To them, he is a hero, the man who as mayor provided desperately needed pensions for the elderly and who tried, at long last, to address Mexico City's traffic gridlock by adding a second level of roadways to the major highways in the capital. When he left office last year, polls showed that more than 80 percent of the city's residents approved of the job that he had done, an unprecedented level of support for a Mexico City mayor.

His supporters also seem untroubled by the scandals that punctuated his tenure as mayor. His finance chief, Gustavo Ponce, who was often spotted at the casino at the Bellagio Hotel in Las Vegas, was accused of involvement in the disappearance of $3 million of municipal funds, while López Obrador's erstwhile personal secretary and close adviser, René Bejarano, was caught on videotape accepting $45,000 from a Mexico City businessman (bribery charges were later dropped). López Obrador suffered no political damage. If anything, his supporters tended to see in these scandals efforts by López Obrador's enemies — in the business establishment and in the Mexican federal government — to discredit him.

López Obrador, who is 53, has often seemed to share his followers' paranoia. When the Ponce and the Bejarano scandals broke — the latter revealed on the TV program of the Mexican journalist Víctor Trujillo, who used to present his spiciest revelations dressed as a clown named Brozo — López Obrador cried conspiracy. Only later did he backtrack to the position that he had known nothing about what his close aides were up to. He has a point, though, when he says that he has been a target of political adversaries who often use questionable methods. In 2004, for example, he was charged with a misdemeanor for ignoring a court order during a land dispute while he was mayor; under Mexico's convoluted election law, that could have barred him from further involvement in politics. The basis for the charge was flimsy at best, but his enemies hoped it might forestall a presidential run by López Obrador, which even then seemed almost inevitable. The accusation provoked mass citizen rallies in support of López Obrador, which effectively forced the authorities to bring the investigation to a premature and inconclusive close.

The devotion that Mexico's poor display for López Obrador, whether merited or not, is one of the principal facts of Mexican politics today. Most of Mexico's underprivileged, who make up nearly half the country's population, believe that Nafta, the North American Free Trade Agreement, has led to hardship rather than to the prosperity they were promised, and these voters view López Obrador almost as a Messianic figure, a savior.

There is a populist groundswell in Latin America at the present moment, and it has swept into power a new generation of leaders, including Néstor Kirchner in Argentina, Evo Morales in Bolivia and Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. For all the differences among these figures, the thread that binds them is a bitter disenchantment with the fruits of globalization and a rising hostility to what, in Latin America, is usually derided as neoliberalism. In some cases, notably that of Hugo Chávez, this discontent has largely found its expression through anti-American vitriol. But there are variants — Kirchner in Argentina is an obvious example — in which Washington plays a secondary role and in which the real animus is toward local elites who, according to the populist indictment, are to blame for their countries' poverty.

López Obrador is the latest and, because of Mexico's political, strategic and economic position, arguably the most significant of all the new Latin American populists. If he succeeds in his presidential bid — a very big "if" as the July 2 elections draw nearer — his victory would cap one of the most important global developments of the past five years: the rapid ascension to power of the left in Latin America. Already it is clear that a serious challenge has arisen to the norms of the modern globalized economy. Even if López Obrador loses, the leftist tide is unlikely to begin to recede anytime soon. Both candidates in the second round of Peru's presidential election were left of center, and in Ecuador, populist policies are increasingly taking hold. But whether Mexican voters realize it or not, their decision on July 2 will serve as a kind of referendum on how far this revolt is going to go. Will it turn out, in retrospect, to have been just a few rogue Latin American countries challenging the global system? Or is this a rebellion that will stretch all the way to the Rio Grande?

Thus the stakes in the Mexican presidential elections are very high, not only for Mexico but for the United States as well. The opening up of the once largely closed Mexican economy has been touted as a great Latin American success story in both Mexico and the United States: the peso is stable, agricultural exports are up and foreign investment is booming. But López Obrador is challenging that story. In fact, he insists, the model has not worked, and he vows that if he is elected, he will pursue a very different set of policies, ones that serve the poor rather than the rich.

As the Mexican historian Enrique Krauze has pointed out, López Obrador's emphasis on his loyalty to the poor connects him, in the mind of much of the Mexican general public, to "the core ideals of the Mexican Revolution." It is common at campaign rallies to see people holding placards with slogans like "López Obrador: For all Mexicans, but first for the humble" and "They will not rob us of our dreams."

To his supporters, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO, as he is popularly known, is simply doing his patriotic duty by running for president, shouldering a necessary burden. To his detractors, he is a politician with a Messiah complex. He wants to push Mexico back 30 years, they say, into the era of President Luis Echeverría, who played upon the left-wing, populist founding traditions of the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party). The PRI ruled Mexico unchallenged from the 1920's until 2000, when Vicente Fox of the right-wing PAN (National Action Party) was elected president. Echeverría made extraordinary promises to the poor, just as López Obrador is doing, and in trying to carry them out, he almost bankrupted the country. Those who oppose López Obrador fear that he will do the same.

López Obrador himself scoffs at these fears. "Change is possible," he told me when we spoke in April on the patio of his home in the gated community of Galaxia in Villahermosa, the capital of his native state of Tabasco. "Of course I understand that globalization is a fact and that one has to act within its parameters. But this does not mean that we here in Mexico have to continue as we have been doing. This country is immensely rich. Its problems are problems of maladministration — above all, of corruption." And he added, "The point is that the Washington consensus" — as the neoliberal model of development is known — "was applied more rigidly here, by successive Mexican governments, than it ever was in the U.S. and Europe, where there are many protected sectors, above all agriculture."

In private, López Obrador speaks with a calm self-confidence that seems almost serene. Nothing in his manner suggests the hard-nosed party politician that he, in fact, is. He began his political career in the 1970's in Tabasco, the hardest of hard-line PRI states, where he emerged as the protégé of the party's leading lights. But in 1988 he bolted from the PRI, which was increasingly dominated by U.S.-educated technocrats, and later joined the nascent Party of the Democratic Revolution, then establishing itself as a left-wing alternative to the PRI. He rose to become the leader of the P.R.D. in 1996. In our conversation, though, questions of political party rarely came up. Instead, López Obrador spoke, as he often does, of his own personal role, which he sees as pivotal. "People expect a great deal of me," he told me, "but I am up to this."

"People say that I am promising too much. But we're talking about a society where 20 million people — 20 million! — live on $2 a day. So when, for example, I talk about giving food aid to the poor, I'm talking about 20 pesos each" — the equivalent of about $2. "And that money — those $2 — would double what these 20 million get and radically change their lives. What the people of Mexico need is not that much, you know."

As he spoke, his tone was almost lyrical. One of López Obrador's early mentors in Tabasco was Carlos Pellicer, a PRI senator who was also a well-known and admired Mexican poet, and there is often the hint of a poet's diction in even López Obrador's most fiery statements. His rhetorical skill no doubt accounts for some of the extraordinary hold he has on the collective imagination of Mexico's poor. When I spoke recently to Jorge G. Castañeda, who served as foreign minister in the first years of Vicente Fox's government and who supports López Obrador's main rival, the National Action Party candidate, Felipe Calderón, Castañeda said that López Obrador's main advantage is simply that "people believe him." While accusing López Obrador of "playing to people's ignorance," Castañeda added that the reason "he has done so well so far is that people believe he believes what he says. He has a way of transmitting his own conviction."

AMLO was the overwhelming front-runner in the first few months of the presidential race. Calderón, who is 43, was a lackluster, uncharismatic campaigner who had not been expected to win even his party's nomination. (The PRI's candidate, Roberto Madrazo, is the scion of a famous Tabasco political dynasty and a former opponent of López Obrador's in Tabasco. Though Madrazo is both experienced and intelligent, he has seemed unable to gain any traction with the Mexican electorate.) In the last two months, however, Calderón has staged an astonishing comeback. He hired new consultants, who, after an internal debate, urged him to "go negative." Ever since, his campaign has been one more demonstration that attack ads work — particularly when the victim fails to answer the attack, as AMLO did. In March and April, the Calderón campaign ran a series of TV spots comparing AMLO with Hugo Chávez, the president of Venezuela, and warning Mexican voters that a López Obrador victory would represent "a danger to Mexico." The spots were withdrawn after the López Obrador campaign lodged a formal complaint with the Mexican electoral commission, but the damage was done. The polls now show Calderón with a lead of about 3 percent — a big turnaround for a campaign that trailed by 10 points as recently as late March.

López Obrador's response to Calderón's attacks has been, on the one hand, to refuse to answer, blandly telling the news media that his only retort to these calumnies will be "peace and love" and, on the other, to campaign even more frenetically across Mexico. It is a killing schedule, substantially more intense than Calderón's (let alone Madrazo's). In a caravan of a half-dozen S.U.V.'s (all of them unarmored), López Obrador has now made at least three stops in every Mexican state, from the impoverished south, where he is overwhelmingly popular, to the Calderón-supporting National Action Party strongholds in the prosperous north-central part of the country.

To follow López Obrador on the campaign trail is to be swept up in something for which the word "populist" seems insufficient. The López Obrador phenomenon seems particularly impressive given how new Mexican democracy is. After all, it was only six years ago that the election of Fox broke the 70-year stranglehold of the PRI. Yes, there were presidential elections during the decades that the PRI ruled Mexico, but the results were always a foregone conclusion. And when a challenger from an opposition party got close, or even received enough votes to win, the results were falsified by the PRI. (Most Mexican observers believe that Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, one of López Obrador's main political mentors and the left's standard bearer in the presidential election of 1988, actually won that election, though he was officially declared the loser.) Sitting Mexican presidents, all of them PRI until 2000, were limited by the Mexican constitution to one sexenio, a six-year term. But, in fact, they had virtual carte blanche to anoint a successor.

Everything changed when Fox, the PAN candidate, won the 2000 elections and the PRI government of Ernesto Zedillo did not try to invalidate the results. But in the minds of many Mexicans, perhaps even a majority, this political transformation was not matched by economic progress. The middle class unquestionably expanded during Fox's term, and along with it grew rates of homeownership and, in certain regions of the country, disposable incomes. But in other parts of the country, the Nafta years were ones of falling incomes and rising joblessness. A result was mass emigration to the United States, enormous even by already-high past standards. "It's not a migration; it's an exodus" was the way one of López Obrador's aides described it. Or, as one Mexican writer put it to me, Fox did create 10 million jobs for Mexicans — unfortunately, they were all in the United States.

López Obrador emphasizes the emigration issue at virtually every campaign stop. Resentment at the treatment of Mexican migrants in the United States is at a fever pitch in Mexico, with practically every affront against illegal workers, real or imagined, getting huge coverage in the Mexican media; the recent pro-legalization rallies in the U.S. were treated with adulation. But López Obrador speaks of emigration as a tragedy for Mexico and as something Mexico needs to put a stop to out of its own national interest. Unlike many Mexican political figures, AMLO doesn't seem to expect the U.S. to continue to accept the current levels of immigration. Nor does he base his economic calculations on the $20 billion that emigrants to the U.S. send home each year, in the process helping to prop up the Mexican economy. And he says that addressing the question will be a priority for his administration.

"If I am elected," he told me, "I will propose a conference on migration with the United States. Building a wall is not a viable solution. The only thing that will work is creating jobs in Mexico. Fox was not able to maintain good relations with Washington. But I can't see any reason why I can't succeed in doing so."

This accomodationist language toward the United States might seem surprising coming from the politician the Calderón campaign has tried to associate with Hugo Chávez, Fidel Castro's greatest ally and the Latin American politician Washington fears most these days. But, in fact, it is consistent with the position López Obrador has taken throughout the campaign. His aides often point out that he has no quarrel with the United States, and in his campaign he reserves his scorn for the political and business establishment of Mexico. Although some American observers remain fearful of his leftist tendencies — The Wall Street Journal ran a column in March worrying that AMLO might be "laying the groundwork for an assault on the private sector" — none of the Americans I spoke to in Mexico seemed to believe that López Obrador will nationalize oil and gas resources, as Evo Morales has done and Hugo Chávez has threatened to do.

The relatively relaxed mood on Wall Street toward a possible López Obrador victory mirrors the dominant view within the Bush administration. One senior administration official, who asked to remain anonymous in order to speak frankly about Mexican politics, put it this way: "I suppose it's a mistake for any diplomat to be sanguine, but insofar as it's possible, we're sanguine about whoever wins the presidency on July 2." This official argued that the system in Mexico has become more powerful than any candidate because the basic structures of a multiparty Mexican democracy governed by the rule of law are now firmly in place and "cannot be undone." Moreover, the official noted that López Obrador had publicly expressed both the desire and the willingness to have a good relationship with the United States and added, "We take him at his word."

The true anxiety over the possibility of a López Obrador victory is to be found in the glass-and-steel towers of Mexico City's business district or in the northern city of Monterrey, where many of Mexico's most successful international corporations are headquartered. There is also clearly anxiety in Los Pinos, the Mexican president's official residence; Vicente Fox has thrown himself into the Calderón campaign in a way that seems less pro-Calderón than anti-López Obrador. AMLO initially responded by calling Fox a "chachalaca," a kind of twittering tropical bird, but as he himself admits, the sally backfired. "Mexican voters don't like personal attacks," he told me ruefully. "I made that mistake with my remark about Fox."

Most Mexican observers will tell you that López Obrador has made other mistakes as well, both in not replying to the attacks the Calderón campaign aimed at him and in refusing to participate in the first televised presidential debate — an event in which an empty lectern was left for López Obrador, Roberto Madrazo behaved with extraordinary clumsiness and Felipe Calderón won handily. So far, though, López Obrador has persisted in shying away from public debates, and he has continued to complain about the way he is being treated in the Mexican media. As a result, his relations with the press are strained.

The recent avalanche of negative stories has only seemed to increase the devotion of López Obrador's followers. Even before he arrives in a town, his supporters are standing along the sides of the roads and down the streets leading to the public square in a state that often seems to verge on the ecstatic. And when López Obrador arrives, it is pandemonium. Usually, he will leap out of his S.U.V. and for a moment will seem to get lost among his supporters before reappearing to lead them, in a noisy procession, toward the jerry-built proscenium from which he will speak.

When he does speak, the effect is electric. Although López Obrador is a brilliant natural orator, his speaking style is not the principal reason for the enthusiastic reaction he elicits. Rather, it is what he promises: new schools, roads, hospitals, oil refineries; improved electricity and clean water; health subsidies for the poor, pensions for the elderly, scholarships for the young; and, above all, jobs. He tells his audiences over and over again that Mexico is a rich country, not a poor one. And decent jobs, he says, will mean Mexicans will no longer have to migrate by the millions to the United States, destroying family stability and communal life and depriving Mexico of its most energetic citizens.

To Calderón's campaign team, López Obrador's unwillingness or inability to explain how he can make good on what he calls on the stump his "commitments" to the Mexican people is his Achilles' heel. "Given the fact that he was mayor of Mexico City between 2000 and 2005, which was when crime reached an all-time high, he should be vulnerable on the security issue," Arturo Sarukhan, a spokesman for the Calderón campaign, told me. "But for whatever reason, he's Teflon on this issue. Where we do have the advantage over López Obrador is on the economic issues. Felipe Calderón can explain how he's going to create jobs. López Obrador can't. It's that simple."

As Castañeda, the former foreign minister, explained it to me: "López Obrador is not Chávez. That's not the problem. What he is, in American terms, is Huey Long in 'All the King's Men,' promising everything to everybody without the slightest idea of how to pay for it. He plays to the democratic inexperience of the Mexican people."

Obviously, that is not the way AMLO's supporters see it. They refuse to entertain the possibility that Mexico may not be able to afford the things López Obrador has committed himself to providing (on the campaign's official Web site they are enumerated, state by state). AMLO bemoans the fact, for example, that Mexico, because of insufficient refining capacity, exports crude oil to the United States that it needs for its own use and then has to buy it back as gasoline. He tells his audiences that he will build three new refineries to lessen Mexico's dependence, reduce prices and boost state revenues. At no point, however, does he explain where the money will come from in the federal budget for the refineries, which cost at least $3 billion each to build, and often much more.

López Obrador is a figure of endless fascination in Mexico. Many Calderón supporters talk far more about AMLO than about their own candidate, and polls show that many Calderón voters are, in reality, anti-López Obrador voters. But there is little consensus about why he does what he does or what he will do in the event that he becomes president. In political terms, as Castañeda points out, López Obrador has assembled a broad coalition of supporters, in contrast to Calderón, who has run "a very PAN campaign, with only PAN candidates and only PAN ideology, reaching out to no one." Castañeda said that AMLO has reached out "to people from the broad swath of Mexican society. He's got people from the old PRI, he's got other people from the P.R.D. — a broad coalition of whoever you can get hold of." He even has some connections in business. His economic team is led by Rogelio Ramírez de la O, a Cambridge-educated economist who is well respected in international business circles. And Carlos Slim, the telecom mogul who is Mexico's richest man and the third-richest man in the world, has let it be known, without formally endorsing AMLO, that he finds nothing alarming about his candidacy.

But if López Obrador really does view himself as a Messianic figure, as someone who can change Mexico through a combination of his own force of will and the support of the masses, technocrats like Ramírez de la O will be unable to rein him in if he is elected. Those who most fear him often assert that he is quite naïve about the world. And it is true that AMLO has traveled very little outside of Mexico. The only major trip he has made — at least the only one he has mentioned publicly — was to Cuba. "He simply doesn't know about the modern world," was the way one writer I spoke to in Mexico City put it. "He thinks he does, but he doesn't." There is a persistent rumor that he prevented his wife, who was mortally ill with lupus and died in 2003, from seeking treatment in the United States or Western Europe (this in a country where the bourgeoisie routinely go to the United States for health care). Of course, to those of López Obrador's followers who credit this story at all, it is further proof of AMLO's patriotism and of his sincerity.

Some activists in the Party of the Democratic Revolution worry that far from doing too much, López Obrador will not do enough if (or, as they almost always put it, when) he is elected president. Hector Ordóñez, a local P.R.D. leader from Ixtapalapa, told me he expected, a year or so after the election, that it would fall to him and his colleagues to explain why López Obrador had not yet fulfilled all of what he had committed himself to. Given the headiness of popular expectations, Ordóñez will have his work cut out for him.

Of course, it is entirely possible that it will be Felipe Calderón who emerges victorious on July 2. He may be dull compared with López Obrador, but he is steady and unlikely to veer very far from the policies pursued by Fox's administration. And while López Obrador's most loyal constituency is made up of people who are worse off now than they were when Fox came into office, the reality is that there are many Mexicans — mostly in the northern half of the country — who are better off. The problem is that since López Obrador's supporters believe he has already won, they are unlikely to accept any other outcome with resignation. In Ixtapalapa, several people told me that they had made a mistake in not taking to the streets in 1988 when Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, the P.R.D.'s founder, was robbed of the presidency by PRI vote-rigging. If they suspect that the election was stolen from López Obrador — and they may not believe any other explanation for a defeat — they would not stand for it. And by his own conduct during the campaign, in which he has never wavered from presenting himself as a president in waiting rather than a presidential candidate, López Obrador has already set the stage for a possible post-election confrontation that would be disastrous for Mexico and, quite likely, for the United States as well.

As Election Day approaches, it is not at all clear whether either López Obrador or Calderón can fulfill the one campaign promise that ordinary Mexicans care most about: massive job creation. Cárdenas, for one, does not think so. While he obviously does not support Calderón, Cárdenas, whom many P.R.D. supporters still refer to as their moral leader, has also declined to back López Obrador. When I met with Cárdenas in April, his gloom about the quality of the campaign was palpable. "A commitment is different from a promise," he told me, a clear allusion to López Obrador's list of "commitments" to the Mexican people. "As far as I'm concerned," he added, "none of the candidates have explained how they are going to do all these things."

When I interviewed Calderón in April, during a campaign swing through his home state of Michoacán, he was dismissive of López Obrador's grasp of global economic realities and of his ability to maintain the confidence of the business community either at home or abroad. And he still says that Mexico must do a better job of competing in the global marketplace. But Calderón now chooses to present himself not as the candidate of a more positive business climate but as "the candidate of jobs," repeating over and over again that it is employment that will be his main focus if he is elected president. And like López Obrador, Calderón is now promising to build new refineries, to expand health care and education and to create opportunity for the millions of Mexicans who will otherwise migrate northward. In recent weeks, the campaign has essentially become a bidding war between the two men over who will create more jobs in Mexico. It is an obvious effort by Calderón to beat López Obrador at his own game — in effect to outbid him on the key issues that most concern Mexican voters.

As the presidential campaign enters its final and critical phase, there is no longer any question of where this campaign is being fought: on the terrain of populism. The fact that Calderón has chosen to challenge López Obrador there, on what had always been AMLO's home ground, is a testament to how much López Obrador's campaign has changed Mexican politics. Of course, if López Obrador goes on to lose an election that, three months ago, most Mexicans thought he would win, that fact is not likely to be much of a consolation to him.

David Rieff, a contributing writer, has reported for the magazine in recent years from Iraq, Bolivia and the West Bank. |

| |

|