|

|

|

Editorials | At Issue | July 2006 Editorials | At Issue | July 2006

Disputed Election Troubles Mexicans

Kevin G. Hall - McClatchy News Service Kevin G. Hall - McClatchy News Service

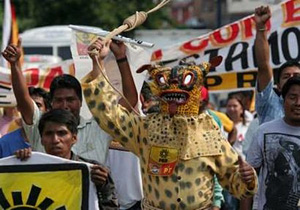

| | Supporters of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, presidential candidate of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), march to demand for a full recount of the July 2 general election in Temixco, in the southern Mexican state of Morelos, July 13, 2006. Angry peasants trudged through the mountains of southern Mexico on Thursday toward the capital in a nationwide protest to support Lopez Obrador, who says he was cheated at the July 2 presidential election. (Reuters/Tomas Bravo) |

The disputed result from the presidential election has left many Mexicans disappointed with their country's fragile democracy.

The fate of Mexico's hotly contested presidential election is in the hands of a special electoral court, which must declare a winner. But for many Mexicans, that result, no matter who wins, amounts to a stain on the country's young and fragile democracy.

"There was manipulation," said Veronica Mendoza, a Mexico City voter who cast her ballot for the apparent winner, conservative Felipe Calderón, yet admits feeling disappointed in the acrimony surrounding the outcome. "I don't know if there was theft, but there was manipulation."

Six years ago, Mexicans celebrated the end of seven decades of often-corrupt rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI in its Spanish initials. Vicente Fox, of the National Action Party, or PAN, a boot-wearing rancher with the rugged good looks of the Marlboro man, had become the first non-PRI politician to win the presidency since 1929, and Mexicans hoped his victory would usher in a new era of untainted elections.

FILING LAWSUITS

But the disputed result of the first presidential election since, with the PAN's Calderón leading by only 243,000 votes out of more than 41 million cast July 2, finds few celebrating now.

The apparent loser, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, of the Party of the Democratic Revolution, or PRD, on Monday filed the last of 152 lawsuits aimed at persuading the Federal Electoral Tribunal, or TRIFE, to order a recount of every vote in every polling station.

The TRIFE (pronounced TREE-fay), which had never been asked to call a presidential election, must rule on those suits by Aug. 31 and declare a winner by Sept. 6.

Mexico's political future hangs in the balance, and Mexicans are trying to figure out whom to blame: Fox, the campaigns or the entire election process.

Fox, a former Coca-Cola executive who once had the reputation of being above the fray, gets the blame from some for his administration's championing last year of an effort to bring criminal charges against López Obrador, who then was Mexico City's mayor, over a minor property dispute. Had the effort been successful, López Obrador would've been barred from running for president. Instead, he became a political martyr.

FOX INTERFERENCE

Once the election campaign began, Fox was perceived as an active participant, in violation of Mexican law. Twice, the Federal Electoral Institute, or IFE, rebuked him for interference.

Gabriel Guerra Castellanos, a political analyst and a former spokesman for a PRI president, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, said Fox and his administration would have better served Mexico's democratic hopes by remaining silent. "The federal government, and the president in particular, have been reckless in speaking out so strongly before the election," he said.

CREDIBILITY

López Obrador's campaign also has problems with credibility. A former member of the PRI, López Obrador surrounded himself with a virtual who's who of ex-PRI members tied to allegations of election fraud.

His campaign chief, Manuel Camacho Solís, held the same position in 1988 for Salinas, who may be the most vilified man in Mexico.

In 1988, Salinas and the PRI narrowly won the presidency after a mysterious computer crash that many Mexicans think was an orchestrated fraud. It fell to Camacho to negotiate on behalf of the PRI to get other parties to accept the tainted results.

In effect, the people crying fraud now are the same ones who denied it in 1988 when the signs were far more obvious.

Opinion polls consistently show that Mexicans hold their political parties in low regard. The same polls showed them trusting the IFE. Until this election, that is.

That's because it failed to deliver a promised quick count, and took nearly three days to acknowledge that while it had said that more than 98 percent of the ballots had been counted, more than 3 million had been set aside for a closer look.

By then, López Obrador was claiming that millions of votes were missing. |

| |

|