|

|

|

Editorials | September 2006 Editorials | September 2006

Armitage Shmarmitage

Jason Leopold - t r u t h o u t Jason Leopold - t r u t h o u t

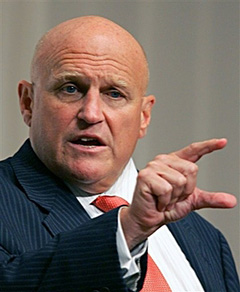

| | Former deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, seen here in July 2006, confirmed in newspaper interviews that he unwittingly outed a secret CIA agent three years ago and expressed remorse for doing so. (AP/Katsumi Kasahara) |

In April, Special Prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald filed a court document in the CIA leak case claiming his staff had obtained evidence during the course of the three-year-old probe that proves "multiple" White House officials were engaged in a coordinated effort to discredit former ambassador Joseph Wilson.

Those officials, Fitzgerald said, eventually disclosed Wilson's wife's covert CIA status to the media as retribution for his public criticism of the Bush administration's use of pre-war Iraq intelligence.

But the mainstream media has chosen to ignore those facts now that former deputy secretary of state Richard Armitage broke his silence Thursday and admitted that he told syndicated columnist Robert Novak and Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward that Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, worked for the CIA.

According to these mainstream publications, Armitage's mea culpa proves there wasn't a White House campaign to discredit Wilson or unmask his wife's identity.

Oh really?

"There exist documents ... that reveal a strong desire by many, including multiple people in the White House, to repudiate Mr. Wilson before and after July 14, 2003," Fitzgerald wrote in the April 5 filing.

In fact, Fitzgerald says it's ludicrous to suggest there wasn't a White House campaign to attack Wilson for criticizing the White House and leak his wife's identity to reporters, given the voluminous documents he has in his possession that prove otherwise.

"Given that there is evidence that ... White House officials ... discussed Wilson's wife's employment with the press both prior to, and after, July 14, 2003, it is hard to conceive of what evidence there could be that would disprove the existence of White House efforts to 'punish' Wilson," Fitzgerald wrote in the court filing.

Perhaps mainstream journalists have declared war on Fitzgerald over the past few weeks because so many of the country's top reporters have been hauled into court against their will by the special counsel to testify before a grand jury about their conversations with White House officials in the leak matter.

But that's no excuse for rewriting history and depriving the public of the truth.

Case in point: according to documents Fitzgerald obtained, the months that preceded the leak saw many unknown officials in the Office of the Vice President hatching a plan to strike back at Wilson, who at the time was urging journalists and lawmakers to hold the Bush administration accountable for using bogus intelligence to win support for a pre-emptive strike against Iraq.

The April 5 court filing says I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby, Vice President Dick Cheney's former chief of staff, and National Security Adviser Stephen Hadley were two of the key figures who were involved in conversations and meetings at Cheney's office in which White House officials discussed ways of striking back against Wilson's criticism of the administration's war effort. Karl Rove was also involved in the discussions.

The court document Fitzgerald filed in April did not name any other White House officials who were involved in the Wilson smear campaign, but it's well-known that Vice President Cheney, Libby and Rove led the effort. Rove told Novak that Plame worked at the CIA on July 8, 2003, the same day Armitage spoke to the columnist. Evidence has not been produced that proves Armitage spoke to Novak first.

Libby - not Armitage - spoke to Judith Miller on July 8, 2003, and told her about Plame's work at the CIA. Moreover, Rove - not Armitage - spoke to Matt Cooper of Time Magazine on July 11, 2003, and told him that Plame worked for the CIA. Libby was indicted on five counts of perjury and obstruction of justice for allegedly deceiving FBI investigators and the grand jury about how he discovered Plame worked for the CIA and whether he shared that with reporters.

During a February court hearing discussing Libby's federal criminal trial, Fitzgerald said Libby was "consumed with [Wilson] to an extent more than he should have been.... When talking about Mr. Wilson for the first time, he described himself as a former Hill staffer. He meets with people off premises. There were some unusual things I won't get into about that week. At the end of the day we're talking about someone who spent a lot of time during the week of July 7 to July 14 focused on the issue of Wilson and Wilson's wife." On July 7, 2003, Libby "had a lunch where he imparted that information in what was described as a weird situation," Fitzgerald said at the hearing.

"He had a private meeting with a reporter outside the White House with this meeting. He was quoted in a very rare interview on a Saturday on the record in an interview with Time Magazine, a very weird circumstance. There are a lot of markers I won't get into that show that this was a very important focus, the Wilson controversy from July 7 to 14, because it was a direct attack on the credibility of the administration, whether accurate or not, and upon the vice president, and people were attacking Mr. Libby. So it was a focus," Fitzgerald said, according to a copy of the court transcript obtained by Truthout.

In the April court filing, Fitzgerald explained how former White House press secretary Scott McClellan came to publicly exonerate Libby and Rove during a press briefing in October 2003, three months after Plame's identity as a CIA operative was unmasked.

The filing suggested that Libby had lied about his role in the leak when McClellan asked him about it in October 2003. Libby, with Vice President Cheney's backing, persuaded the press secretary to clear his name during one of his morning press briefings, and prepared notes for him to use.

"Though defendant knew that another White House official had spoken to Novak in advance of Novak's column and that official had learned in advance that Novak would be publishing information about Wilson's wife, defendant did not disclose that fact to other White House officials (including the vice president) but instead prepared a handwritten statement of what he wished White House Press Secretary McClellan would say to exonerate him:"

"People have made too much of the difference in

How I described Karl and Libby I've talked to Libby.

I said it was ridiculous about Karl.

And it is ridiculous about Libby.

Libby was not the source of the Novak story.

And he did not leak classified information."

"As a result of defendant's request, on October 4, 2003, White House Press Secretary McClellan stated that he had spoken to Mr. Libby (as well as Mr. Rove and Elliot Abrams) and 'those individuals assured me that they were not involved in this,'" Fitzgerald said in the April 5 court filing.

McClellan's public statement and the fact that President Bush vowed to fire anyone in his office involved in the leak were motivating factors that led Libby to lie during an interview with FBI investigators in November 2003.

"Thus, as defendant approached his first FBI interview, he knew that the White House had publicly staked its credibility on there being no White House involvement in the leaking of information about Ms. Wilson and that, at defendant's specific request through the vice president, the White House had publicly proclaimed that defendant was 'not involved in this,'" Fitzgerald states in the court filing.

Jason Leopold is a former Los Angeles bureau chief for Dow Jones Newswire. He has written over 2,000 stories on the California energy crisis and received the Dow Jones Journalist of the Year Award in 2001 for his coverage on the issue as well as a Project Censored award in 2004. Leopold also reported extensively on Enron's downfall and was the first journalist to land an interview with former Enron president Jeffrey Skilling following Enron's bankruptcy filing in December 2001. Leopold has appeared on CNBC and National Public Radio as an expert on energy policy and has also been the keynote speaker at more than two dozen energy industry conferences around the country. |

| |

|