|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | October 2006 Editorials | Issues | October 2006

Humble Donkey Reclaiming Its Place

Humble Donkey Reclaiming Its Place Humble Donkey Reclaiming Its Place

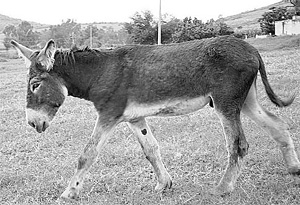

| | In six months, "The Precious One" has impregnated about 20 horses. The resulting mules will be sturdy agricultural workers. (Sara Miller Llana) |

A single donkey the locals call "The Precious One" stands alone, grazing in a field with the low mountains of western Mexico in the background.

But burros, or donkeys, once thronged the country's dirt roads. Mules — the hybrid offspring of male donkeys and female horses — hauled everything from maize to Mexicans, laying down tracks extending from Veracruz to the state of Mexico.

Once a symbol of farm life, donkeys today are often dismissed and derided as an indicator of underdevelopment. Over the decades, their role in plowing fields and carrying wood has been usurped by trucks and tractors. Instead of carrying goods, donkeys have been sent to the slaughterhouse to feed more esteemed creatures like cows.

But some Mexicans are wondering if they have taken their disdain for the sinewy equine a bit too far, and say the nation faces a shortage of animals that, it turns out, can do things tractors can't — like work a narrow furrow or get up a particularly steep incline. The agricultural state of Jalisco responded last year by importing male donkeys from Kentucky to bolster, with the help of horses, their mule population — giving the donkey a 21st-century cachet in the age of John Deere.

The Precious One was donated to the Cofradia Ranch, part of the University of Guadalajara, six months ago. Leonel Gonzalez Jauregui, executive director of the research ranch, says he wants to create a breeding center that will turn out sturdy mules to help local producers work their fields and remain competitive.

In six months, The Precious One has impregnated about 20 horses, he says. "This program can help us give to the people."

Donkeys, first brought to Mexico by the Spanish in the 1500s, flourished here for centuries.

The animals lost popularity with the introduction of machines that could do the same work.

Donkeys have never been terribly loved. As in English, their name can be used to hurl an insult — stubborn as a mule, dumb as a donkey.

"There are lots of donkeys here," Gonzalez Jauregui says with a smirk. "Just not the animal."

If all of Mexico's geography were accessible by tractor, and if all farmers could afford a tractor, the demise of the donkey or mule might otherwise have gone unnoticed.

But many of the small tracts that characterize much of Mexico's farmland are not compatible with tractors.

Another factor in the donkey's favor: the rising cost of fuel. "In many communities, the cost of the crops is less than the cost of fuel," says Patrick Fenton, director of the Kentucky Agricultural and Commercial Trade Office.

Aline de Aluja, a veterinarian at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, says the Jalisco program could help preserve the livelihoods of small landowners who are increasingly under assault by U.S.-style mechanization.

"Small landowners can't exist in this American culture," she says. "The Jalisco program's aim is to reintroduce donkeys into agriculture." |

| |

|