|

|

|

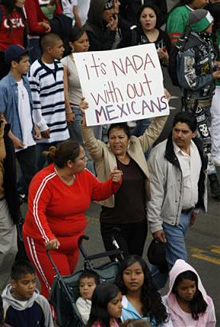

Editorials | Issues | October 2006 Editorials | Issues | October 2006

Job Demand Spurs Border Crossing

Wire services Wire services

| | The United States must recognize that without the complimentary resource of Mexican labor it would have serious problems in areas like agriculture. |

Somewhere north of this Mexican cattle outpost, U.S. National Guard troops man 24-hour observation posts and better-equipped U.S. Border Patrol agents roam the desert, searching for illegal immigrants.

Yet even as the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush points to a drop in apprehensions at the border as proof that the new security measures are working, thousands of Mexicans and Central Americans still gather daily in border towns like this, willing to risk anything for a slot in the U.S. labor market.

"There´s a lot of migra now, mucha migra, but I must keep trying," said Felipe Pérez, 30, using the name migrants collectively call the border forces.

Pérez wiped away rivulets of sweat as he shouldered his backpack for a second attempt in 48 hours to climb over the wire cattle fence dividing this section of Sonora from Arizona. Once over, he planned to walk toward Phoenix, through the kind of 100-plus-degree heat that killed 267 migrants in Arizona alone last year.

But Pérez´s determination is no blind desperation - like most others making the trek, he not only knows he´ll find work in the United States, he knows exactly what he will be doing, for whom and where.

In a mix of Spanish and English, he ticked off his past jobs: picking tomatoes in Florida and building homes in the Rockies. Now, after a visit home to Mexico, he was eager to get back to a construction job awaiting him in Colorado Springs.

No amount of enforcement, it seems, can counterbalance the fundamental motivations for crossing the border illegally.

Hurricanes wreaked havoc in Mexico´s far south and Central America last year, prompting migration from places where it had been rare. Small Mexican farmers increasingly find they can´t compete with bigger domestic producers or U.S. imports. Most industrial and service jobs still pay a pittance south of the border, migrants complain, and factory jobs assembling clothes for U.S. chain stores pay poorly, too.

By contrast, there is no shortage of promises of jobs from family and friends in the United States. Sometimes U.S. employers even assure veteran undocumented workers that they will hold a job open for them while they visit an ailing parent or a pining spouse back home.

Eliezar Reyes was pondering a second attempt at crossing through Sasabe precisely because of a call from Florida to his home in the state of Veracruz.

"In January, the boss called me. I mean, he told someone who speaks Spanish to call me and tell me there was work waiting for me," said Reyes, 24.

Three years ago, Reyes started mowing golf courses in St. Augustine, Florida, then moved into construction, earning US$100 a day. He took a break last November to visit his wife in Mexico.

His construction boss was able to reach him there, Reyes said, because he had earned enough in the United States to have a telephone installed back home.

For those lacking a close connection to a U.S. boss, the smugglers known as coyotes make the link to employment.

In Tijuana, at a government-run shelter for underage deportees, 16-year-old Juan José Pérez told his story. From fieldwork starting at age 12 in the state of Jalisco, he had gone on to work construction in San Diego.

"I was given the name of a gringo coyote, a Mr. Wilson," he said. The man came to Pérez´s Tijuana hotel to tell him whom to meet for his trek over mountains east of Tijuana. The smuggler also helped Pérez get a job renovating houses.

"Wherever you go there´s corruption," Pérez said, eating cereal on his bunk bed at the shelter. "The gringos at work said, ´If the migra comes, you just run.´ "

He´d be in the United States still, Pérez added, had he not been caught driving a car without a license.

Even before President Bush ordered U.S. National Guard troops to the border in May, the United States had invested billions over the past decade attempting to block illegal immigrants from crossing in urban areas, such as Tijuana and El Paso.

That pushed migrants into Arizona´s desert and other isolated terrain, resulting in a 500 percent increase in deaths between 1994 and 2004, according to the California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation. More than 3,000 fatalities have been recorded since the mid-90s, and hundreds of bodies and bones remain unidentified, according to the CRLA Foundation and Mexico´s Foreign Relations Secretariat.

Human rights activists have long objected to a border policy they consider not only cruel but contradictory, given that U.S. employers still hire undocumented immigrants.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and major labor unions also have become migrant allies. They support proposals in the U.S. Congress to increase immigrant and temporary work visas. Currently, low-skilled immigrant work visas are capped at 5,000 a year.

At the border, however, the political dispute often is expressed in simpler, personal terms.

"It looks like they don´t like us but they want us for the work," said Oscar Galindo, 18, who had been deported earlier that day to Nogales, Sonora, a city separated from Nogales, Arizona, by a 10-foot metal fence.

Galindo had hoped to trade a waiter job paying US$5 a day, plus tips, in Tlaxcala for work in Queens, New York, restaurants with his uncle.

Traveling with Galindo was Federico Ramírez, 24, who hoped to reach a place he called "Co-neck-tee-coot."

"New Haven," he added, where his parents have been living since he was 16.

"My mother went, my father went, my sister went and now I´m going," Ramírez said, trying to sound determined.

The two watched a U.S. activist clean the injured feet of Armando Chávez, 26, whose family in New York had agreed to pay US$2,000 in smuggling fees, on delivery.

Chávez grimaced as the volunteer from the Tucson-based No More Deaths poured a saltwater solution onto his split toes. He accepted a pair of new socks before limping toward a man whispering advice about how to get over the line.

No More Deaths has drawn both criticism and praise for providing water and food to migrants in the desert. Another group, Humane Borders, has erected water stations marked by blue flags.

"This is an issue that seems to cut to the hypocrisy of the United States today," said No More Deaths volunteer Charles Vernon, 30, a Colorado school bus driver, sitting in the shade of a tarp, handing out water.

"These are jobs we need people to do," Vernon said. "But we´re going to make it as hard as possible for people to get into the United States to do them."

Virginia National Guard volunteer Sgt. Clyde Hester sat on a hill just across the border from Vernon, scanning the horizon through binoculars.

"I can see the point of view of these people; however, I´ve got a job to do," said the Iraq veteran from Lee County, Virginia.

Hester wore a flak jacket and had an automatic weapon at his side, but his orders were to observe and report suspicious movement to the U.S. Border Patrol.

"We´ve got lots of unemployed people where I´m from," Hester said. "Of course, you have to find someone willing to work. We got people on welfare for generations."

About 40 percent of the 6,000 National Guard troops on border duty were sent to Arizona because of its popularity as a crossing point.

U.S. Needs Immigrant Labor, Says García

Patrick Harrington - El Universal

Over 400,000 Mexican immigrants enter the United States annually seeking legal and illegal work.

Economy Secretary Sergio García de Alba said a proposed 700-mile (1,125-kilometer) border wall could disrupt trade between the two countries and lead to a shortage of farm laborers in the United States.

"Any worry should be bilateral," García said during an interview in Mexico City. The United States must "recognize that without the complimentary resource of Mexican labor it would have serious problems in areas like agriculture."

García´s comments form part of a backlash among Mexican officials against approval by U.S. lawmakers last week of heightened security measures along the border including the fence. Such measures are politically motivated and offer only a short-term solution to stemming immigration, Garcia said.

"During all of the discussions that I have had as economy secretary with business leaders in the United States, all of them are against the decisions of radical politicians," he said.

A lack of job prospects prompts more than 400,000 Mexicans to enter the United States each year seeking work both legally and illegally, according to the Pew Hispanic Center in Washington.

"The people who emigrate are often the most entrepreneurial and hard working," García said.

Both Mexico and the United States would benefit from investment to make the border more orderly and efficient, which would improve security and facilitate trade, García said.

"The wall is really a bad investment," he said. "But, well, we understand that there are some politicians who have a short-term view and use these kinds of measures as part of a campaign process." |

| |

|