|

|

|

Editorials | October 2006 Editorials | October 2006

From Chiapas to the Zócalo: Popular Uprisings in Mexico

John Gibler - towardfreedom.com John Gibler - towardfreedom.com

| | "The rich can’t always win." |

Jose Santiago sits in front of the radio station’s guarded door with a box of bread rolls in his lap. To his left, soda crates filled with Molotov cocktails line the wall. To his right two women with a club stretched between them block the door. A 62 year-old elementary school principal in Oaxaca City, Santiago was supposed to retire this year, but when state police brutally repressed a teachers’ strike on June 14, sparking an unprecedented civil uprising from all sectors of society, he thought, "I’d rather jump in."

"I’m ready," he says as he waits to deliver his donation of bread rolls to the teachers camping out behind the barricades that protect the occupied radio station, "even if the army comes in."

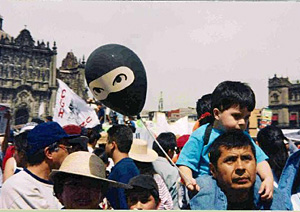

Santiago and hundreds of thousands like him have raised their voices and taken to the streets across Mexico during the past year, pushing the boundaries of traditional methods of organizing to carry out creative, high-stakes social protests. Recent social movements in Mexico, including the Zapatistas’ Other Campaign, the teachers’ strike-turned-uprising in Oaxaca, and the post-electoral protests in Mexico City, have together pulled some 3 million people into the streets, captured national and international attention, and raised the bar for civic protest in response to fraud, corruption and repression.

All three movements, which share both an overlap of rank and file participants and an intricate web of hostile accusations between leaders and pundits, have suffered in varying degrees from government repression and proposed both thick and thin alternatives to the dominant neo-liberal economic policies of the ruling National Action Party (PAN). The Other Campaign is the more elusive and ambitious movement, with heavy emphasis on long-term organizing and a clean break from capitalism and political parties. Meanwhile, the Oaxaca uprising is more muscular, with its weight behind civil disobedience tactics aimed at shutting down the state government and taking over media. The post-electoral fight is the most spectacular, with its goals split between civil disobedience and long-term organizing.

These protest and social movements show that working class Mexicans are not planning to take another 6-year presidential term of cartel market policies lying down. On December 1, Felipe Calderon (PAN), already pursued by protests and accusations of electoral fraud, will assume the presidency with a weak mandate - only to face some of the strongest organized popular resistance in decades.

The Other Campaign Builds from Below

On January 1, 2006, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) initiated the Other Campaign, a call to bridge the struggles of the marginalized and the exploited to abandon political parties and the capitalist economic system they serve. The Other Campaign aspires to a radical transformation of Mexican political life, nothing less than the construction of a grassroots people’s government that would overthrow the political ruling class.

The Other Campaign is quixotic in the extreme, but not foolhardy. The Zapatista initiative has walked its talk by setting out to spend the next several years building a national organization. They have sent Subcomandamte Marcos on a six-month nationwide listening tour to hear from the underdogs of the Mexican left, and then sent a commission of Zapatista commanders to spend 6-month periods organizing in all 30 states and the federal district of Mexico City, (1).

For four months, as Marcos drove the country’s back roads, the Other Campaign drew participation from indigenous communities, farm-workers, factory workers, sexual diversity groups, women’s organizations, environmentalists, sex workers, intellectuals, artists, anarchist-punk collectives, and street kids. The tour made several daily stops—seven days a week—in rural communities, inner-city slums, and downtown plazas. Marcos often spoke in public to encourage people to join and participate in the Other Campaign, but the backbone of the tour consisted in the hours-long town hall meetings where Marcos—and the motley crew of organization representatives and independent media correspondents who followed him—sat quietly listening to the stories of resistance and autonomous governance projects.

The Other Campaign’s listening tour came to a halt in Mexico City on May 3, when Marcos heard reports of violent police repression of flower vendors in nearby Texcoco, Mexico State. Marcos suspended his activities for that day and called the EZLN to be on red alert.

Early that morning state and local police attempted to force flower vendors from the sidewalks near a market in Texcoco. The People’s Front in Defense of Land from neighboring San Salvador Atenco—a farmers’ organization famous for beating back President Vicente Fox’s plans to appropriate their lands for a new Mexico City airport in 2002—sent a group of some 30 activists to support the flower vendors. As they marched toward the market, police began to detain and beat them with batons. Most escaped and retreated to a nearby house, calling to their colleagues in Atenco for support. In an attempt to force the police to negotiate, the Atenco farmers blocked the federal highway that borders their town. Instead of sending a negotiation committee, the government sent state and federal police to lift the blockade, leading to violent clashes between the farmers and the police that left dozens injured on both sides, and one 14 year-old boy killed by police gunfire.

The following day, May 4, over 2,000 federal, state and local police raided Atenco at dawn, lifting the highway blockade and brutally beating and detaining 207 people. The scale of police violence on May 4 was shocking. Police went house to house shooting tear gas through windows and dragging sleepy residents out into the streets for beatings. Once loaded into buses and pickup trucks, police drove detainees out into the countryside for torture and further beatings before taking them to jail. Police sexually assaulted—and in some cases raped—45 women (the governmental National Human Rights Commission finally released a recommendation on October 16 stating that police had sexually assaulted "at least 26 women"). Entering in the morning, police fired tear gas grenades at protesters, hitting 20 year-old Ollin Alexis Benhumea in the head. Alexis went into a coma and died a month later. Six months later, no government official has been held responsible, while 47 people are still in jail on trumped up charges.

The day after this brutal smack down Marcos led a march into Atenco where he declared the Other Campaign tour to be indefinitely suspended, promising to remain in Mexico City to help organize to demand the release of the then 207 people in jail. After months of holding marches and maintaining a protest camp outside the jail, members of the Other Campaign decided to continue their tour in October, calling upon a delegation of Zapatista commanders to travel from Chiapas to Mexico City to continue the organizing in Atenco.

The Other Campaign has been mostly ignored or misunderstood by reports. Indeed, the prospect of overthrowing the government and uprooting capitalism by first touring the country listening to people is truly daunting. What the press has missed however has not been the story of a rebellion in its early embryonic stage, but rather the everyday tales of repression and resistance, of suffering marginalization and building autonomy that the Other Campaign has brought to the surface.

PAN Takes the Elections, Protesters Take Mexico City

While the Other Campaign was winding its way across the southern and central states of Mexico, the presidential campaigns made their own noisy and vitriolic stops across the country. Five candidates ran for president, but the battle between the two frontrunners dominated the headlines and exposed deep class divisions in Mexican society.

Felipe Calderon Hinojosa, of the right-wing PAN and Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador of the center-left Democratic Revolution Party (PRD) took to attacking each other with unrestrained vigor. Calderon, in a word, swift-boated Lopez Obrador, running countless television adds calling him a "danger for Mexico," linking him to Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez and images of Hitler. Obrador failed to challenge or respond to these adds for months—when he finally did, Mexico’s federal electoral court ruled them off the air—but the damage had been done and his support in the polls dropped several points.

However, the demonization of Lopez Obrador actually began over a year earlier with an attempt to block his candidacy through accusations that he had violated a court order to stop construction on a hospital access road while serving as mayor of Mexico City. Lopez Obrador mobilized hundreds of thousands of supporters in massive marches and eventually the federal government dropped the charges.

In turn, Lopez Obrador lashed out at Calderon as a representative of the oligarchy that has pillaged Mexico for decades, linking him to past and present corruption scandals. While the cards were stacked against him, Lopez Obrador did make a few political miscalculations that led to further drops in the polls: he let the attack adds go unanswered for months, failed to attend the first debate, where Calderon dominated and attacked him, and he called President Fox "a noisy bird" and told him to "shut up," which—like Howard Dean’s scream—was attacked in the media as "not presidential behavior."

The feeling on the July 2 election day was tense and bitter. Calderon’s supporters used racial epithets to denigrate Lopez Obrador’s supporters. "Abajo con los pinches nacos" ("Down with the f-ing indians") supporters shouted at Calderon’s campaign headquarters, while Lopez Obrador’s supporters shouted slogans about crushing the oligarchy.

Throughout the campaign season, Subcomandante Marcos lashed out at all three major candidates, Calderon, Lopez Obrador, and Roberto Madrazo of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Marcos’ critiques of Calderon and Madrazo were equally scathing, but his attacks on Lopez Obrador attracted the most media attention. This led many to believe that Marcos only sought to cut down Lopez Obrador and thus played into the designs of the rightwing.

Marcos’ critique of Lopez Obrador consisted of four parts: the PRD’s past treatment of the Zapatistas, his tenure as mayor of Mexico City, his campaign team, and his welfare reform program. First, his party, the PRD, stabbed the Zapatistas in the back in 2001 by voting for a gutted version of an indigenous rights law that the Zapatistas had advocated for through a national caravan and a speech in Congress. Later, the PRD sent paramilitary groups into Zapatista communities in Chiapas. Second, as mayor of Mexico City, Lopez Obrador catered to the upper class neighborhoods, allowing Mexico’s richest man, Carlos Slim, to buy up countless properties in the city’s historic center. He also repressed social movements, and turned his back when human rights lawyer Digna Ochoa was assassinated in 2001, and Mexico City public defenders—after months of baffling legal incompetence—declared that she had committed suicide. Third, he filled his campaign team with ex-PRI officials who have had their hands in everything from the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement to brutal acts of repression. Fourth, he promoted a welfare-like program of reforms within the capitalist economic system in Mexico that Marcos accused of being mere band-aids aimed at containing social unrest without challenging the position of the ruling class.

While the stage was set for a tense day of voting, no one expected what was to come. At 11 pm on July 2, Luis Ugalde, the head of the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE), was shown in a pre-recorded message saying that the early election results were to close to call and that the IFE would not release them. Ugalde called on all candidates to refrain from declaring victory until the IFE had release the preliminary vote count—both Calderon and Lopez Obrador ignored him and declared victory later that night. Less than a minute after Ugalde’s message ran, confused news broadcasters switched to another pre-recorded message, this time by President Fox praising the "impartiality" and "scientific objectivity" of IFE and calling on Mexicans to sit tight for the results.

What followed was an absurd show of vote counting theatrics that left an irremovable stain on the 2006 elections, (2). By July 3, Lopez Obrador claimed fraud and called for a vote-by-vote recount. His campaign team put together a thousand-page complaint alleging widespread fraud that they submitted to the Federal Electoral Tribunal to support their recount demand. Over the next month Obrador convoked and led three massive marches in Mexico City, each one bigger than the previous. After the third march, on July 31, which some claim pulled nearly 2 million people into the streets, Lopez Obrador called on his supporters to set up camp in the Plaza de la Constitución, or Zócalo, the symbolic core of the nation, and down several major avenues that stretch for miles through downtown Mexico City. Tens of thousands heeded his call.

Throughout August, Obrador camped out with his supporters in the Zócalo holding nightly "informational assemblies" at 7 pm. The Zócalo protest was a strange creature, borne of an uncommon union between a major political party and a genuine grassroots mobilization. Most detractors on the right belittled the conviction of the thousands who filled the protest camps, while most supporters on the left ignored the open wallet and heavy hand of the PRD in the movement. While thousands of people contributed their spectacular creativity to the post-electoral protest movement, the organizing structure never broke free of the top-down control exercised by Lopez Obrador and the PRD, (3).

This dynamic was most poignantly illustrated by the movement’s culmination in the National Democratic Convention (CND). The CND, scheduled for September 16, Mexican Independence Day, was billed grandiloquently as the assembly where Mexico would vote for a "legitimate president" and lay the groundwork for a "government in rebellion." Lopez Obrador and CND organizers proclaimed their intention to fill the Zócalo with a million "delegates" from across the country, set up discussion tables down major avenues and convoke proposals and then vote. As the date approached and the daunting challenge of organizing such a convention hit home, organizers scaled back their projections in interviews and said that the CND would be "symbolic" rather than a true declaration of a government in rebellion, (4).

When the day arrived, the CND successfully pulled over a million people into the Zócalo. But the CND differed only cosmetically from the previous mass gatherings in support of Lopez Obrador. People were asked to raise their hands to "vote" on yes or no questions decided by Obrador and his team. The rank and file played no meaningful organizing or participatory role beyond wearing badges around their necks and raising their hands. Moreover, when the massive crowd attempted to make their voice heard, stepping out of the yes-or-no pin, Obrador and his team ignored them. The crowd had been asked to approve the entire leadership of the resistance movement—30 people—in one vote, yes or no. While the list of names including some old-school PRI crooks and completely lacked in ethnic, geographic and—to a lesser extent—sexual diversity, there was one name on the list that had been so sullied by recent scandals that the huge throng of "delegates" began to shout: "Imaz no! Imaz no!" The Master of Ceremonies, Jesusa Rodriguez, paused, waiting for the cries to die down and then moved on. After a few hours, the crowd was released with no homework assignment, and told to come back in six months.

The attitude of the people on the stage with Lopez Obrador was quite discordant with the mood on the street. Those who filled the Zócalo that day had bigger plans than a symbolic "government in resistance." They had concrete ideas they wanted to put into play. But they did not have a way of expressing those ideas to the crowd, and the people on the stage steered clear of the civil resistance tactics being discussed in the crowd.

Cuautemoc Salas, a 40 year-old manual laborer from Iztapalapa, a poor sprawling area of Mexico City, and member of the Valentin Campa Union of infrastructure repair workers said that he was ready to stop paying federal taxes to the "illegitimate government" and to boycott transnational corporations. He proposed using those savings to build cooperatives, develop national production, and eventually create an alternative currency.

Salas believed that the movement would take off and become the spearhead of national resistance to Calderon and his ambitions to privatize much of Mexico’s public sector and many of its protected natural resources.

"This is not a movement of the PRD," he said. "This is a national movement that went beyond the PRD; it is a movement of the people."

Oaxaca Uprising

Several months before the presidential election, on May 22, only three weeks after the brutal crackdown in Atenco and as the electoral campaigns entered into their final lap of epic mudslinging, about 60,000 teachers sat down in Oaxaca City’s touristy central plaza and refused to leave. The teachers strung up tarps from trees and lampposts, built fire pits and improvised kitchens, and installed the transmitter of their pirate radio station, thus constructing a tent city in the heart of Oaxaca.

Section 22 of the National Union of Education Workers, a dissident wing within the famously corrupt national union, has been fighting to improve Oaxaca’s neglected rural schools for 26 years. This past April, they began a campaign to rezone Oaxaca’s slot in the federal budget allotment scheme and thus demand better wages and a higher education budget to provide for school repairs, supplies, lunches, and uniforms. The state government, led by Ulises Ruiz Ortiz of the PRI, also elected under allegations of fraud in 2004, refused to meet with the teachers to discuss their demands. So the teachers went on strike and set up their tent city, something they have done almost every year for the past 26 years, (5).

This year, Ulises Ruiz decided to send 1,000 state police in to break the teachers strike by force. The police raided the tent city just before dawn, unleashing attack dogs, firing tear gas from helicopters hovering over the plaza, and storming the sleeping teachers in riot gear. Police beat scores of people severely with their batons, burnt down the tent city, and decimated their pirate radio equipment.

The teachers and Oaxaca City residents responded in an obviously unanticipated manner. They regrouped and then surrounded the police, fighting with sticks, rocks, and Molotov cocktails. By the early afternoon the teachers had regained the plaza. Within two days they convoked a march of over 400,000 people and formed the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO), grouping the teachers union together with hundreds of local and statewide organizations and newly formed neighborhood associations.

The APPO—now calling for Ulises Ruiz’s resignation or ouster as their sole and non-negotiable demand—reinforced the teachers’ protest camp, convoked massive marches, and, starting in late July, initiated a series of civil disobedience tactics aimed at paralyzing the state government and forcing the Senate to intervene. They blocked government office buildings, including the State Legislature and the Governor’s office, painted the entire town with calls for Ulises Ruiz’ ouster, and eventually took over several state and commercial media transmitters. For months Ruiz has been unable to walk freely in Oaxaca City, and not a single uniformed police officer has set foot in central Oaxaca since June 14.

Ulises Ruiz said he would not resign, but that he "remained open to dialogue." The APPO refused to acknowledge Ruiz as governor and had no direct contact with the government until a series of stop-and-start talks with the Minister of the Interior in August and September. The federal government refused to force Ruiz out, Ruiz refused to leave, and the APPO refused to release their grip on Oaxaca City.

In August paramilitary gunmen began to open fire on protest marches and encampments, killing seven people and wounding a dozen more by mid October. The APPO has denounced these attacks, used their occupied radio stations to organize people to defend the camps, set up thousands of makeshift barricades at night throughout Oaxaca City, and even apprehended several gunmen and turned them over to federal authorities. In a press conference after a shooting in August, Antonio, one of the APPO’s provisional leaders said that they would "only respond with organization" to paramilitary violence, defying the state government’s attempt to paint the APPO as an "urban guerrilla" movement.

In late September, 4,000 teachers and members of the APPO marched over 250 miles from Oaxaca to Mexico City. Upon their arrival on October 9, they set up a protest camp outside of the Senate and, a week later, began a hunger strike of 21 people.

"This march is an example that our movement is one where people are prepared to make sacrifices, and example of dignity," said Fernando Soberanes, a member of an indigenous teachers coalition founded in 1974, who had walked with the march for all 19 days through four states. He added that the march was also, "a school for the young people in the movement, to teach them that the struggle is no game."

The Senate sent a commission to Oaxaca to analyze the conditions for an effectual dissolution of the state government and was scheduled to vote on the issue on October 17. The threat of a major police or military operation to lift the protest camps has the APPO on red alert and many human rights organizations in Mexico and abroad sending urgent actions calling on the government to avoid repression at all costs.

In the latest case of paramilitary violence against protesters, just days after the Senate commission visited Oaxaca, soldiers in civilian clothes shot at an APPO barricade, killing 41 year-old Alejandro Garcia Hernandez. At 2:30 am on October 14, Hernandez was giving home-brewed coffee to the barricade guards with his wife and son when the soldiers opened fire. A 19 year-old APPO member at the barricade took a bullet in the shoulder when he jumped in front of Henandez’s son who had rushed to his father’s aid. In their escape one of the soldiers, Johnatan Rios, dropped his wallet, spilling and leaving behind on the road his federal identification card and a receipt from the Mexican military bank.

[Note: At 9 pm on October 18, as this article was in the final stage of editing, gunmen shot and killed Panfilo Hernandez, a preschool teacher, as he stepped out of a meeting with other teachers and members of the APPO in the Jardín neighborhood of Oaxaca City.]

Where Will it all Lead?

"We see this as a historic opportunity," said Ernesto Ledesma, director of the Chiapas-based Center for Political Analysis and Social and Economic Research, "the Mexican political system is in crisis."

Barricade in Oaxaca

Ledesma called for the creation of "strategic alliances" across these movements, acknowledging differences, but seeking to use the power of union to confront the weakened legitimacy of the ruling oligarchy.

It is impossible to guess what form the three movements discussed in this article will take over the next 6 years. The post-electoral fight could dissolve or evolve into an anti-privatization front focusing on opposing Calderon. The APPO may break apart or grow stronger after Ulises Ruiz falls from power or the army is brought in to occupy Oaxaca City. The Other Campaign may continue to organize at the grassroots under the radar of the press or ignite a major battle such as the fight to oppose the La Parota dam in Guerrero state. What is certain is that organized social resistance is on the rise in Mexico and will be a source of inspiration for activists across the world.

Pedro, a 45 year-old teacher guarding commandeered big-rig trucks that the APPO protesters use to shut off the highway at night, captured the spirit of many of the everyday citizens who have left their daily routines to join the Other Campaign, the post-electoral fight, or the Oaxaca uprising when he explained to me, "The rich can’t always win."

John Gibler is a Human Rights Fellow at Global Exchange.

Sources and further information:

(1) Chronicles from the first four months of the Other Campaign

(2) A closer look at the vote-count irregularities

(3) A report on the Mexico City protest encampments

(4) A report on the National Democratic Convention

(5) An excellent look at the Oaxaca teacher’s movement in national context, see Jill Freidberg’s documentary "Granito de Arena" |

| |

|