|

|

|

Editorials | Environmental | October 2006 Editorials | Environmental | October 2006

Porpoises Dying Off

Kaitlin Manry - Everett Herald Kaitlin Manry - Everett Herald

| | Some killed by fungus that can also be deadly to people. |

Unusually high numbers of harbor porpoises are dying in Washington waters.

It's unclear what is causing the trend, but necropsies have confirmed that some of the porpoises died of Cryptococcus gattii, a fungus that has killed four people in British Columbia.

In humans, the disease affects the lungs and nervous system.

Other than a few isolated occurrences in aquarium animals, this is the first time the microscopic fungus has appeared in the United States.

Some doctors and veterinarians fear the airborne fungus is moving south from Canada. Scientists do not think the fungus is contagious.

"It is a rare disease here - and possibly an emerging disease," said Mira Leslie, who until recently was the state's public health veterinarian.

In Whatcom County last year one cat died of the fungus and two others were infected, Leslie said.

The fungus grows on trees. It is invisible to the human eye. As leaves dry out, it can become airborne and land in nearby water.

Necropsies have confirmed that 25 porpoises have died of the disease in the Pacific Northwest since 1999.

All but six of the infected animals washed up in British Columbia. The rest were found in Washington.

It's unclear why the other porpoises have died, said Stephen Raverty, a veterinary pathologist with the Animal Health Center in Abbotsford, B.C.

Raverty has studied the disease since its outbreak and has conducted necropsies on many of the diseased animals.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's marine mammal stranding network ships porpoises that wash up in Washington to Raverty for necropsies.

Cryptococcus gattii first sprang up on Vancouver Island in 1999. Two years later, it spread into the world's first multispecies outbreak of the fungus, Raverty said.

Porpoises, dogs, cats, llamas, ferrets, pet birds, horses and humans became infected.

By the end of March 2002, laboratory tests confirmed that 50 humans and 45 animals had the disease. The B.C. Center for Disease Control now estimates that 25 people become sick with cryptococcus each year. Anti-fungal treatments are available.

Last year, the disease was found in the Vancouver Island coast and Fraser River health districts of British Columbia.

No one is sure how cryptococcus gattii wound up in B.C. It is typically found in eucalyptus trees in the tropics of Australia.

Some think the fungus was carried to British Columbia on a ship, a eucalyptus tree or even on the bottom of someone's shoes.

Others think the fungus has lived in British Columbia for years but wasn't a threat to animals until temperatures increased.

"Part of the hypothesis is that because of increasing global temperatures, the environmental conditions are better" for growth, Raverty said.

Laboratory tests indicate the fungus can reproduce in salt water.

Raverty thinks porpoises become infected when they inhale a small amount of pathogen-filled water in their blow holes.

The disease spreads to their lungs, often causing lesions. Many of the affected porpoises wash ashore emaciated.

Not all animals or humans exposed to the fungus become infected.

Scientists are working to determine whether porpoises are becoming sick from U.S. water, or if they are infected in British Columbia and then swim into Puget Sound before dying.

"It's difficult to really put this in context if there's a point source of exposure or if there (are) multiple places where these animals are exposed," Raverty said. "We expect the latter, though."

It's also unclear how the Whatcom County cats came down with cryptococcus gattii. They had different owners and aren't believed to have traveled to B.C.

"We think the cats acquired the illness in Washington state - and that would be a first," said Leslie, who is currently an adjunct professor at Washington State University.

A Washington man was also diagnosed with the disease, but he likely picked it up while traveling, she said. He recovered.

After the cats were diagnosed, Leslie warned veterinarians and physicians throughout Washington to watch for the disease.

Whatcom County Health Officer Dr. Greg Stern also put the word out in the medical community.

He said he's asked local doctors to test patients who exhibit signs of cryptococcus gattii: prolonged coughing, fevers, severe headaches, weight loss and night sweats.

"We don't want people to be worried about it," he said. "We just want them to be prudent. If they're ill, they should get medical treatment. Their physicians will be considering it more as a cause of illness as we identify more cases."

Scientists aren't sure if, or how much, cryptococcus gattii is to blame for the recent surge in harbor porpoise deaths in Washington.

There's been a surge in Oregon as well.

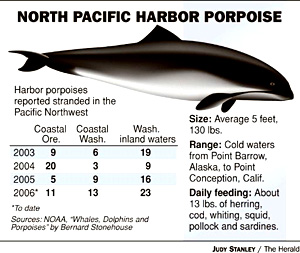

The annual average of dead porpoises reported to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's marine mammal stranding network had hovered around 30 since 2003.

So far this year, 47 harbor porpoises have been found in Washington and Oregon. Most have washed ashore in the inland waters of Washington, said Brent Norberg, NOAA's Marine Mammal Coordinator for the Northwest region.

Reports of dead porpoises have been made throughout the year but increased during the summer.

Raverty said about 10 percent of the those porpoises tested positive for the fungus.

Another 40 percent died of undetermined causes. Many of the dead porpoises are juveniles. Most cryptococcal infections occur in adult animals.

"So far all we know is there's an elevated number, and we're trying to figure out if that means something," Norberg said.

Reporter Kaitlin Manry: 425-339-3292 or kmanry@heraldnet.com. |

| |

|