|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | December 2006 Editorials | Issues | December 2006

Few Really Know Calderón; His Actions Will be the Key

S. Lynne Walker - Copley News Service S. Lynne Walker - Copley News Service

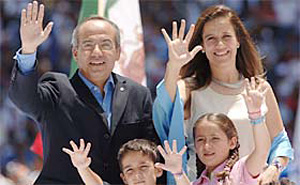

| | Felipe Calderón and his wife, Margarita Zavala, are former members of Congress from the PAN. Their three children include Luis Felipe (left) and Maria. (Luis J. Jimenez/Copley News Service) |

As Mexico's new president takes the oath of office today, two critical questions remain: Who is Felipe Calderón, and how will he govern his splintered country?

An attorney and career politician, the low-key Calderón is still a mystery to most Mexicans.

People know his face. They know he has promised to be a “jobs president” and to use a “firm hand” with lawbreakers. They know he is a conservative from outgoing President Vicente Fox's National Action Party, or PAN.

But they have few clues, even now on inauguration day, about how Felipe Calderón will confront Mexico's toughest problems.

“The big, big question is how he is going to use his presidential power,” said Oscar Aguilar, a political science professor at Mexico City's Universidad Iberoamericana. “He has to demonstrate his character the first day of his administration. That is what we are all waiting for.”

Those who know the 44-year-old Calderón say he will bring a new style of governing to Mexico.

“He is accustomed to negotiating. He is a person who places importance on the Congress,” said Soledad Loaeza, a professor of political science at the Colegio de Mexico. “He is strong-willed and persistent and disciplined. He is a fighter.”

His first fight comes today, when he has vowed to go to the Mexican Congress and take the oath of office, despite efforts by the rival leftist party to stop him.

“I will go to the Congress not out of capriciousness or because of political strategy but simply because that is what the Constitution says,” Calderón said yesterday.

Calderón is known for playing by the rules.

“He is a product of democracy,” Aguilar said. “He was not the president's candidate. He was not his party president's candidate. But by following the rules, he won the presidency.”

During his years as a legislator he earned a reputation for being interested in cutting deals rather than preserving the party line.

“I saw him demonstrate very sensible attitudes in legislative negotiations,” said Juan Gabriel Valencia, a congressman with the rival Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, during Calderón's 2000-03 term in the Congress. “He was a man who was prepared to look for solutions without worrying about partisan phobias.”

But many wonder whether Calderón's sharp negotiating skills will be enough to resolve the burdensome problems he inherited from Fox.

To reform the energy sector, to make fiscal reforms, to make structural changes in the political system, Calderón must win two-thirds of the Senate and the lower House of Congress.

“He knows how to negotiate tight little deals,” said political analyst Federico Estévez. “But is he capable of the big vision? We don't know. He really hasn't presented a plan for huge changes.”

Calderón faces other challenges as well.

Drug cartels are gaining control of cities and towns across Mexico. Guerrilla groups have threatened to bring down his presidency. And there is the unfinished business of curbing the poverty that affects half of Mexico's population.

Elected to his first congressional post in his mid-20s, Calderón earned a law degree, then a master's in economics at the prestigious Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico. He later earned a master's degree in public administration from Harvard University.

By all accounts, he is not a charismatic leader. His speeches are sometimes dull and often emotionless. He does not easily forget a slight and some say he is prone to lose his temper.

“He will be a president who is distant from the masses, who will be perceived as isolated, without a public image that excites public opinion,” Valencia said. “But he can compensate for that with results. And he is a man of results.”

That Calderón is being inaugurated today is a triumph to his dogged determination to succeed.

He is the son of middle-class parents from the farm state of Michoacan, and Calderón's tale “is an old-fashioned story about a young professional who works his way to the top,” Estévez said.

Calderón's father was a devoted member of the PAN, even serving as the party's semi-official historian.

“This was a family out of the provinces, decent folk, very righteous. Kind of mainstream Mexico,” Estévez said. “They led a fairly modest existence, but this was an intellectual family so they made sure all their children were educated.”

Calderón handed out party leaflets as a kid and painted fences with PAN logos. He also served as secretary of the party's national youth movement.

His wife, Margarita Zavala, was a PAN congresswoman, and he proposed to her on the campaign trail. By 1996, he had risen to party president.

Still, few expected Calderón to ascend to the nation's top political post.

When he began his presidential campaign in January, “He was the least-known of the candidates,” said Loaeza. While leftist rival Andrés Manuel López Obrador basked in national attention, fewer than 40 percent of Mexicans knew who Calderón was.

As Calderón prepares to face a hostile Congress at his inauguration ceremony, political analysts said his hope for a successful six-year term rests on finding a way to patch together the profound divisions caused by the presidential election.

“He will only be able to do it with actions, with results,” Aguilar said. “Felipe Calderón has to give clear indications about what his government is going to do and start working the first day to end conflicts in this country.”

S. Lynne Walker: slwalker@prodigy.net.mx |

| |

|