|

|

|

Editorials | January 2007 Editorials | January 2007

The Tough Get Going

The Economist The Economist

| | During the seven decades of rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the main objective of policing was political control rather than crime fighting. |

The new president has sent the army after the drug mobs. More importantly, he has started to reform the police.

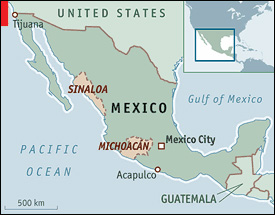

He took office as Mexico's president only on December 1st, but Felipe Calderón has lost no time in putting pressure on the country's powerful drug gangs. Last month he dispatched 7,000 troops and police to the central state of Michoacán. Forces of similar size have since been sent to Tijuana on the northern border, and to the Pacific resort of Acapulco. On January 19th, the government extradited four drug kingpins and a dozen lesser figures to the United States for trial. Notably, they included Osiel Cárdenas, the head of the so-called “Gulf Cartel”, by far the most powerful drug gangster to be extradited so far.

This flurry of action responded to a “real anxiety in some parts of the country” that organised crime was “out of control”, Mr Calderón told El País, a Spanish newspaper, this week. There were 2,100 drug-related murders last year, up from 1,300 in 2005. Some 600 killings took place in Michoacán alone in 2006. Many of the murders involved brutal cruelty: in a notorious case, five severed heads were dumped in a dance hall in Michoacán. Much of the violence stems from a turf war between the Gulf Cartel and its main rival, based in Sinaloa. Paradoxically, this was triggered by arrests made by the previous government of Vicente Fox.

Two things compound the problem. The first is the continuing demand for drugs across the border in the United States. The second is that during the seven decades of rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, defeated by Mr Fox in 2000, the main objective of policing was political control rather than crime fighting.

That is why Mr Calderón turned to the army. The first thing the troops did on arrival in Tijuana was to disarm the local police, confiscating their guns for ballistics tests to check whether they had been used in murders. Like many ill-paid local forces in Mexico, the Tijuana police are widely regarded as working for, rather than against, the drug mob.

The risk, of course, is that the army becomes corrupted. But unlike Mr Fox, Mr Calderón is moving swiftly to shake up the police. As a first step, the federal police is being expanded and re-organised in the public-security ministry. The Federal Agency of Investigation (AFI), a newish and relatively uncorrupt police force modelled on America's FBI, has been transferred to the ministry from the attorney-general's office. It is being merged with another force, the federal preventive police. The risk, of course, is that the army becomes corrupted. But unlike Mr Fox, Mr Calderón is moving swiftly to shake up the police. As a first step, the federal police is being expanded and re-organised in the public-security ministry. The Federal Agency of Investigation (AFI), a newish and relatively uncorrupt police force modelled on America's FBI, has been transferred to the ministry from the attorney-general's office. It is being merged with another force, the federal preventive police.

The security minister, Genaro García Luna, was the commander of the AFI and is a career detective. He says that 10,000 soldiers have been transferred to his control, giving him a force of just over 30,000. A national motor-vehicle registry, which Mexico has previously lacked, should be up and running within a year. Mr García wants to establish benchmarks for police performance, at both federal and local levels, in order to increase accountability. He also wants to regulate Mexico's 140,000 private security personnel.

Some of these changes, such as formalising the transfer of the AFI to the ministry, require legislation. Mr García says the government will send a bill to Congress in a month or so; it has a good chance of being approved. The government also wants to reform the local police. On January 22nd, Mr García signed an agreement with Mexico's 32 state governors that will give him powers to intervene in local forces. It is not clear whether money will be available to increase police wages, which average around $500 a month, although the government has increased soldiers' pay.

Some of the government's opponents dismiss the military operations as political grandstanding. But even if the message they send is partly symbolic, it is an important one. So far they have yielded no accusations of systematic abuses and one or two significant arrests.

The difficulty is what comes next. Mr García says that the federal forces will be deployed for several more months—at least for long enough for the local forces to be investigated and re-trained. It is, of course, impossible to imagine that Mr Calderón will achieve total victory over the country's drug industry. But he might at least manage to reduce the degree of impunity with which it operates. |

| |

|