|

|

|

Editorials | Environmental | January 2007 Editorials | Environmental | January 2007

Fight for Survival at Sea

Sandra Dibble & Mike Lee - San Diego Union-Tribune Sandra Dibble & Mike Lee - San Diego Union-Tribune

| | In an undated photo, dead vaquitas were lined up on a beach. (Marine Fisheries Service) |

San Felipe, Mexico – Few people have ever seen a vaquita porpoise. Scientists estimate that no more than 400 of the elusive marine mammals are alive today.

But the world's smallest porpoise is attracting international attention. With recent news of the extinction of the baiji dolphin in China's Yangtze River, the question is whether Mexico's vaquita will be the next cetacean to vanish.

Despite years of efforts to protect the vaquita, its population in the northern Gulf of California is shrinking by an estimated 30 per year.

“If we don't do our job, another species will disappear,” said Lorenzo Rojas Bracho, a scientist with Mexico's National Institute of Ecology.

Vaquita conservation efforts have ramped up in the past couple of years, thanks partly to an agreement among one-time rivals – a major seafood company based in San Diego, Mexican fishermen and several U.S. environmental groups. Such programs are unlikely to save the vaquita unless their funding grows significantly.

“The biggest challenge is changing the custom of the fisherman,” said Miguel Angel Cisneros, head of Mexico's National Fisheries Institute. “It would be difficult for them to stop fishing from one year to the next. It has to be a gradual process.”

Vaquitas grow to about 5 feet and 120 pounds and travel in groups of two or three, so they are difficult to find, let alone study. Scientists track their movements with a radar that detects the creatures' acoustic pulses, or clicks.

“It's a very shy species, very hard to approach, very hard to see,” Rojas said.

Earlier this month on the gulf, also known as the Sea of Cortez, it was easy enough to see bottlenose dolphins. Hundreds leapt from the water in an afternoon feeding frenzy near Rocas Consag, a rocky islet off the fishing town of San Felipe.

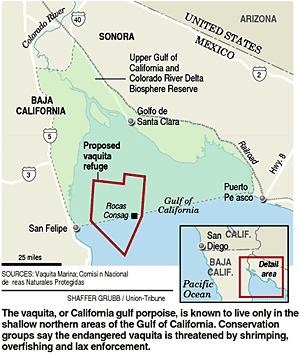

But there were no vaquitas, even though this spot in the gulf is within the 500-square-mile vaquita refuge decreed by the Mexican federal government last year. But there were no vaquitas, even though this spot in the gulf is within the 500-square-mile vaquita refuge decreed by the Mexican federal government last year.

Riding on the small boat, or panga, that skipped across choppy swells, Román Antonio Cano clearly remembered the day he and a companion spotted a pair of vaquitas. Their small spouts and black rings around the eyes left no doubt.

“I could see them very clearly,” said Cano, 22, a fisherman, smiling broadly at the memory. “They jumped once, they jumped twice, and then they disappeared.”

Vaquitas mainly are killed as “by-catch” in the gill nets used by hundreds of fishermen in the northern Gulf of California, a prime shrimp-fishing ground and the only place the vaquita lives. Like other marine mammals, vaquitas must surface to breathe and drown when trapped in the nets.

At first, many believed that vaquitas died only in larger-mesh nets and steps were taken to ban them. But scientists now say vaquitas also can end up trapped in the smaller-mesh nets used to catch shrimp.

Survival of the species means getting rid of nets altogether, said Rojas, who is the chairman of the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita.

For a long time, many fishermen denied the vaquita's existence. Some still insist that it is not gill nets that have caused the declining vaquita population, but the reduction of freshwater flows from the Colorado River into the Gulf of California.

“They said that all pangas and boats affect the vaquita, and it's not true,” said Alberto Garcia Orozco, a member of the family-owned Faro Garcia Fishing Cooperative in San Felipe.

Garcia and others insist that more studies are needed. Rojas says the data are indisputable and by the time studies would be completed, the vaquita may well be extinct.

Getting rid of gill nets means negotiating with hundreds of fishermen of the Upper Gulf, persuading them to use alternative fishing methods or to find other means of support.

“It's very difficult to change the way we fish for shrimp,” said Andres Rubio, a retired fishermen who advises an association of 17 fishing cooperatives in San Felipe.

fisherman Antonio Iñiguez, 59, said saving the vaquita is important: “If we eliminate the species, we're altering the life in the Gulf of California,” said Iñiguez, a fisherman for almost 30 years and member of the Felipe Angeles Fishing Cooperative. “We're not going to turn a deaf ear to clamors from the rest of the world.”

The vaquita is listed as a critically endangered species by the World Conservation Union. China's baiji had the same designation until overfishing, pollution, boat traffic, coastal development and other factors affecting the Yangtze River led to its disappearance.

“The marine mammal community was shocked at how fast the baiji disappeared,” said Robert L. Pitman, a marine ecologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, who participated in last year's fruitless search for the baiji.

“These animals do go extinct, and fishing by-catch can be what pounds in the last nail in the coffin.”

Faced with only one major threat – getting snagged in gill nets – the vaquita's situation is easier to solve, environmentalists say.

Calls to protect the vaquita helped prompt the Mexican government to create the Upper Gulf of California Biosphere Reserve in 1993, a management plan that banned large-mesh gill nets used to catch totoaba, a large fish that was also endangered. Vaquitas kept getting caught in smaller-mesh nets, and scientists have concluded that any gill-net fishing poses a threat.

San Felipe, Puerto Peñasco and Golfo de Santa Clara are the major fishing communities affected by efforts to protect the vaquita. On a busy day in shrimping season, which typically runs from mid-September to mid-March, 1,000 boats may be in or near the reserve, director Jose Campoy said.

“It's not easy to persuade a group of people that has been fishing for a long time,” Campoy said. “The best way is to do it bit by bit, tightening the rules, but at the same time offering opportunities.”

In Puerto Peñasco, the Intercultural Center for the Study of Deserts and Oceans has been working to offer alternatives to fishing, such as training and incentives to take up ecotourism. At Golfo de Santa Clara, the World Wildlife Fund has been testing a shrimp-fishing net known as the zuripera that skims the bottom and does not threaten the vaquita.

In 2005, the Natural Resources Defense Council took a different tack, reaching an agreement with Ocean Garden – the San Diego-based company that markets the fishermen's shrimp – the fishing communities, government officials and several other environmental groups. The fishermen agreed to stop using nets with mesh measuring 6 inches and larger that are most harmful to the vaquita.

“Implementation has been difficult and slow,” said Ari Hershowitz of the Natural Resources Defense Council. “We have a lot of good will from the fishermen and we have a clear plan, but (replacing large-mesh nets) is going to require money from people who are interested in saving the species.”

The agreement also produced Alto Golfo Sustentable, a forum for parties to continue discussing conservation. “We're clearly more able to listen to each other. . . . We have a much better potential to solve the problem,” said Alejandro Robles, president of Noroeste Sustentable, a group of conservation-minded businessmen.

In September 2005, the Mexican government took a major step by designating a vaquita refuge in the area where most vaquita sightings have occurred. The measure included $1 million to compensate affected fishermen and help them find alternatives to gill net fishing.

The government has yet to take the final step in formalizing the refuge, which is to include a restricted zone where all gill nets are banned.

Still, Rojas said the refuge “is like taking an aspirin against cancer.” Phasing out gill nets is the only solution, but without finding alternatives for fishermen, “you would save the vaquita, but then send into extinction so many families that it would be unfair,” Rojas said.

Reached by telephone in Golfo de Santa Clara, fisherman Jesús Camacho, 37, is preparing to set aside his nets. With money from Mexico's federal government, his 32-member cooperative purchased a boat this month that it will use for ecotours and sportfishing.

“I'd say there are many like me who would be ready to do what it takes to preserve the vaquita,” Camacho said. “But there have to be alternatives. If you gave us alternatives, half of us would be willing to stop fishing.”

Sandra Dibble: (619) 293-1716; sandra.dibble@uniontrib.com |

| |

|