|

|

|

Editorials | Opinions | January 2007 Editorials | Opinions | January 2007

The Mentally Ill, Behind Bars

Bernard E. Harcourt - NYTimes Bernard E. Harcourt - NYTimes

Last August, a prison inmate in Jackson, Mich. — someone the authorities described as “floridly psychotic” — died in his segregation cell, naked, shackled to a concrete slab, lying in his own urine, scheduled for a mental health transfer that never happened. Last month in Florida, the head of the state’s social services department resigned abruptly after having been fined $80,000 and is facing criminal contempt charges for failing to transfer severely mentally ill jail inmates to state hospitals.

Ten days ago, the Supreme Court agreed to determine when mentally ill death row inmates should be considered so deranged that their execution would be constitutionally impermissible. The case involves a 48-year-old Navy veteran who is a diagnosed schizophrenic. In the decade leading up to the crime he was hospitalized 14 times for severe mental illness.

According to a study released by the Justice Department in September, 56 percent of jail inmates in state prisons and 64 percent of inmates across the country reported mental health problems within the past year.

Though troubling, none of this should come as a surprise. Over the past 40 years, the United States dismantled a colossal mental health complex and rebuilt — bed by bed — an enormous prison. During the 20th century we exhibited a schizophrenic relationship to deviance.

After more than 50 years of stability, federal and state prison populations skyrocketed from under 200,000 persons in 1970 to more than 1.3 million in 2002. That year, our imprisonment rate rose above 600 inmates per 100,000 adults. With the inclusion of an additional 700,000 inmates in jail, we now incarcerate more than two million people — resulting in the highest incarceration number and rate in the world, five times that of Britain and 12 times that of Japan.

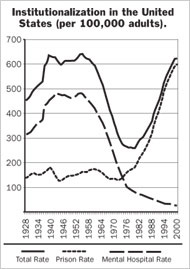

What few people realize, though, is that in the 1940s and ’50s we institutionalized people at even higher rates — only it was in mental hospitals and asylums. Simply put, when the data on state and county mental hospitalization rates are combined with the data on prison rates for 1928 through 2000, the imprisonment revolution of the late 20th century barely reaches the level we experienced at mid-century. Our current culture of control is by no means new.

The graph on the left — based on statistics from the federal Census Bureau, Department of Health and Human Services and Bureau of Justice Statistics — shows the aggregate rate of institutionalization per 100,000 adults in the United States from 1928 to 2000, as well as the disaggregated trend lines for mental hospitalization on the one hand and state and federal prisons on the other. The graph on the left — based on statistics from the federal Census Bureau, Department of Health and Human Services and Bureau of Justice Statistics — shows the aggregate rate of institutionalization per 100,000 adults in the United States from 1928 to 2000, as well as the disaggregated trend lines for mental hospitalization on the one hand and state and federal prisons on the other.

The numbers include only state and county mental hospitals. There were many more kinds of mental institutions at mid-century, ones for “mental defectives and epileptics” and the mentally retarded, psychiatric wards in veterans hospitals, as well as “psychopathic” and private mental hospitals. If we include residents of those facilities, from 1935 to 1963 the United States consistently institutionalized at rates well above 700 per 100,000 adults — with highs of 778 in 1939 and 786 in 1955. It should be clear why there is such a large proportion of mentally ill persons in our prisons: individuals who used to be tracked for mental health treatment are now getting a one-way ticket to jail.

Of course, there are important demographic differences between the two populations. In 1937, women represented 48 percent of residents in state mental hospitals. In contrast, new prison admissions have consistently been 95 percent male. Also, the mental health patients from the 1930s to the 1960s were older and whiter than prison inmates of the 1990s.

But the graph poses a number of troubling questions: Why did we diagnose deviance in such radically different ways over the course of the 20th century? Do we need to be imprisoning at such high rates, or were we right, 50 years ago, to hospitalize instead? Why were so many women hospitalized? Why have they been replaced by young black men? Have both prisons and mental hospitals included large numbers of unnecessarily incarcerated individuals?

Whatever the answers, the pendulum has swung too far — possibly off its hinges.

It would be naïve, today, to address any of these questions without also considering the impact of imprisonment on crime. One of the most reliable studies estimates that the increased prison population over the 1990s accounted for about a third of the overall drop in crime that decade.

However, prisons are not the only institutions that seem to have this effect. In a recent study, I demonstrated that the rate of institutionalization — including mental hospitals — was a far better predictor of serious violent crime from 1926 to 2000 than just prison populations. The data reveal a robust negative relationship between overall institutionalization (prisons and asylums) and homicide. Preliminary findings based on state-level panel data confirm these results.

The effect on crime may not depend on whether the institution is a mental hospital or a prison. Even from a crime-fighting perspective, then, it is time to rethink our prison and mental health policies. A lot more work must be done before proposing answers to those troubling questions. But the first step is to realize that we have been wildly erratic in our approach to deviance, mental health and the prison.

Bernard E. Harcourt, a professor of law and criminology at the University of Chicago, is the author of “Against Prediction: Profiling, Policing and Punishing in an Actuarial Age.” |

| |

|