|

|

|

Health & Beauty | January 2007 Health & Beauty | January 2007

Recipe for Disaster

Clark Spencer - Miami Herald Clark Spencer - Miami Herald

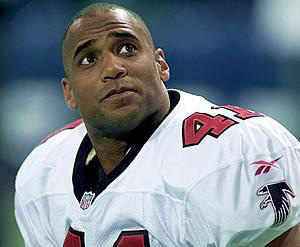

| | TWO FACES: The night after Eugene Robinson got a citizenship award, he was arrested for soliciting an undercover police officer. (Miami Herald) |

Thomas "Hollywood" Henderson ingested cocaine on the sideline of the Orange Bowl during Super Bowl XIII, inhaling the diluted product from a Vick's nasal sprayer that the flamboyant linebacker for the Dallas Cowboys had kept inside his uniform pants - but not for the high.

Henderson's nostrils had become so damaged from his frequent snorting that he said he craved the drug strictly to deaden the pain, to enable him to breathe freely in order to run and make tackles.

"In my own sick mind, it was medication," Henderson said. "I had become Dr. Henderson - ear, nose and throat doctor - because the raw nature of snorting cocaine up my nose abusively created sores in my septum. I was addicted to cocaine, but the side effect was a huge booger in my nose that hurt like hell. It was gross. I would shower and blow my nose until this thing flew out and hit the wall. That was part of the pregame routine."

That also was part of Henderson's pregame routine before the 1979 Super Bowl in Miami, before the Cowboys lost to the Pittsburgh Steelers. Henderson, 53, who devotes his life to helping others with drug problems through his counseling program and motivational-speaking engagements, said he isn't proud of that past, which includes a prison sentence for drug-related offenses.

But he holds it up as an example that, contrary to its myth-like aura, the Super Bowl is not larger than life. It is the other way around, and it helps to explain why a running back for the Cincinnati Bengals succumbed to a drug-induced haze before Super Bowl XXIII in Miami, and why a safety for the Atlanta Falcons was picked up for soliciting sex from an undercover police officer before Super Bowl XXXIII, also in Miami, just hours after he received an award from the Fellowship of Christian Athletes.

It helps to explain why an offensive lineman for the Oakland Raiders went AWOL from the team, seen drinking in Tijuana, Mexico, during the week leading up to Super Bowl XXXVII in San Diego, and why a defensive lineman for another Raiders team went out drinking in New Orleans before Super Bowl XV and was fined for violating curfew.

It helps to explain why Green Bay Packers receiver Max McGee was out partying all night before the first Super Bowl in 1967, yet managed to catch seven passes, including two for touchdowns, after being thrust into action when the team's starting receiver left the game because of an injury.

'JUST ANOTHER GAME'

"You can call it super, or duper, or the whopper," Henderson said. "But for the guys who play the game, it's just another game. You're bringing 106 lives, and then you add the coaches and there are 146 lives. You're bringing good marriages, bad marriages, kids in trouble, alcoholism, drug addiction. You're bringing, 'I had a fight with my wife' and 'My significant other's not talking to me.' It's 146 stories."

Former pro running back Chuck Muncie, whose teams never reached the Super Bowl but whose NFL career was checkered because of drug issues, agreed with Henderson. Like Henderson, Muncie spent time behind bars because of drug-related violations. And also like Henderson, Muncie has created his own foundation in which he counsels others with drug problems.

"Nothing surprises you about any of it," Muncie said.

Muncie, a three-time Pro Bowl running back during nine seasons with the New Orleans Saints and San Diego Chargers in the late 1970s and early 1980s, said some players probably do not know how to react when they get to the Super Bowl.

"All of a sudden, you're going through an event that you've worked so hard to achieve that you start celebrating as soon as the [conference] championship game is over," Muncie said. "They go out celebrating, and those people that have addictive personalities [don't] know how to stop the situation from escalating. They're used to being in a mode where the season is over, and now they're bringing their friends out to this thing, creating their own worst environment."

"Why would a guy do that knowing what's at risk? They get so caught up in it, they start big-timing it, and they take things out of perspective."

The late John Matuszak of the Oakland Raiders pronounced that he was going to roam the streets of New Orleans to make sure his younger teammates did not get out of line.

"I'm going to see that there's no funny business," Matuszak proclaimed before the 1980 Super Bowl. "I've had enough parties for 20 people's lifetime. I've grown up."

But Matuszak was seen drinking and dancing at a Bourbon Street nightclub at 4 a.m., five hours past curfew, and he was fined.

Eugene Robinson, a safety for the Atlanta Falcons when they played in the 1999 Super Bowl, the last played in Miami before this year, was by all accounts a model citizen. The Fellowship of Christian Athletes presented him with an award the day before the Super Bowl.

But Robinson was arrested that night on Biscayne Boulevard for attempting to solicit an undercover cop for oral sex.

Stanley Wilson was not a model citizen. He had violated the NFL's drug policy twice when the Bengals, with Wilson as their running back, hit South Florida in 1989 for Super Bowl XXIII. But Wilson didn't make the game after a coach found him huddled in his room at a Plantation Holiday Inn, with cocaine powder clinging to his upper lip.

DRUG-INDUCED HAZE

"We were all flabbergasted when [Bengals coach Sam Wyche] told us that Stanley Wilson would not be able to play this game because we found him in a drug-induced haze," said Boomer Esiason, the Bengals' quarterback at the time. "That's when my teammate, Cris Collinsworth, got up and said, îWe've got to win this one for Stanley,' and that's when everyone wanted to bum-rush him and beat the hell out of him, because Stanley had been a three-time loser already and now the night before the biggest game he let it happen again."

Said Henderson: "I think one of the most tragic stories of all of our stories is the Stanley Wilson story, one that I understand very clearly."

Before Super Bowl XIII, Henderson delivered one of the game's most enduring quotes, saying Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw "couldn't spell cat if you gave him the C and the A."

But Henderson was battling a cocaine addiction and, to prepare for the Super Bowl, took an empty bottle of Vick's nasal spray and filled it with a diluted cocaine concoction. He said he ingested some in the locker room before the game and kept the container hidden in his pants during the loss to the Steelers.

"I knew that I would have a severe headache and a face pain if I didn't dilute some cocaine in liquid form and use it to anesthetize the nose," he said. "I wasn't using cocaine to enhance. In my own sick mind, it was my medication."

Henderson never revealed the incident until much later. Now, he said, he has been clean from alcohol and drugs for 23 years, but carries the scars from his long-ago habit - a hole in his septum.

cpsencer@MiamiHerald.com - Miami Herald sportswriter Barry Jackson contributed to this report. |

| |

|