|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | February 2007 Editorials | Issues | February 2007

Families Behind Bars: Jailing Children of Immigrants

Kari Lydersen - In These Times Kari Lydersen - In These Times

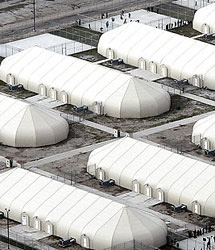

| | About 2,000 illegal immigrants are being held in the T. Don Hutto Correctional Center in Taylor, Texas, awaiting deportation to their home countries. They may wait months or years even though they have been charged with no crime. The federal government pays the nation's largest private prison company $95 per person per day to house them as they await deportation proceedings. (Kirsten Luce/Washington Post) |

Thanks to US immigration policy, children (including infants and toddlers) whose parents are in immigration courts, are being locked up at detention centers.

Named after the co-founder of the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the T. Don Hutto Correctional Center in Taylor, Texas, opened as a medium-security prison in 1997. Today, the federal government pays CCA, the nation's largest private prison company, $95 per person per day to house the detainees, who wear jail-type uniforms and live in cells.

But they have not been charged with any crimes. In fact, nearly half of its 400 or so residents are children, including infants and toddlers.

The inmates are immigrants or children of immigrants who are in deportation proceedings. Many of them are in the process of applying for political asylum, refugees from violence-plagued and impoverished countries like Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Somalia and Palestine. (Since there are different procedures for Mexican immigrants, the facility houses no Mexicans.)

In the past, most of them would have been free to work and attend school as their cases moved through immigration courts. "Prior to Hutto, they were releasing people into the community," says Nicole Porter, director of the Prison and Jail Accountability Project for the ACLU of Texas. "These are non-criminals and nonviolent individuals who have not committed any crime against the U.S. There are viable alternatives to requiring them to live in a prison setting and wear uniforms."

But as a result of increasingly stringent immigration enforcement policies, today more than 22,000 undocumented immigrants are being detained, up from 6,785 in 1995, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Normally, men and women are detained separately and minors, if they are detained at all, live in residential facilities with social services and schools. But under the auspices of "keeping families together," children and parents are incarcerated together at the T. Don Hutto Residential Center, as it is now called, and at a smaller facility in Berks County, Penn. Attorneys for detainees say the children are only allowed one hour of schooling, in English, and one hour of recreation per day.

"It's just a concentration camp by another name," says John Wheat Gibson, a Dallas attorney representing two Palestinian families in the facility.

In addition, there have been reports of inadequate healthcare and nutrition.

"The kids are getting sick from the food," says Frances Valdez, a fellow at the University of Texas Law School's Immigration Law Clinic. "It could be a psychological thing also. These are little kids, given only one hour of playtime a day, the rest of the time they're in their pods in a contained area. There are only a few people per cell so families are separated at night. There's a woman with two sons and two daughters; one of her sons was getting really sick at night but she couldn't go to him because he's in a different cell. One client was pregnant and we established there was virtually no prenatal care."

When local staff for the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) collected toys for the children at Christmas, Hutto administrators would not allow stuffed animals to be given to the children, according to LULAC national president Rosa Rosales.

"That's what these children need - something warm to hug," she says. "And they won't even allow them that, why, I can't imagine. They say they're doing a favor by keeping families together, but this is ridiculous."

A CCA spokesperson refers media to the San Antonio office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), but that office did not return calls for this story.

Immigrants have been housed at the facility since last summer, and public outrage and attention from human rights groups has grown in the past few months as more people have become aware of the situation.

In mid-December, Jay J. Johnson-Castro, a 60-year-old resident of Del Rio, Texas, walked 35 miles from the Capitol to the detention center, joined by activists along the way and ending in a vigil at the center.

"Everyone I have talked to about this is shocked that here on American soil we are treating helpless mothers and innocent children as prisoners," says Johnson-Castro, who had previously walked 205 miles along the border to protest the proposed border wall. "This flies in the face of everything we claim to represent internationally."

A coalition of attorneys, community organizations and immigrants rights groups called Texans United for Families is working to close the facility. The University of Texas Immigration Law Clinic is considering a lawsuit challenging the incarceration of children.

Valdez sees the center as a political statement by the government.

"Our country likes to detain people," says Valdez. "I think it's backlash for the protests that happened in the spring - like, 'We're going to show you that you're not that powerful.' It's about power."

Kari Lydersen writes for the Washington Post out of the Midwest bureau and just published a book, Out of the Sea and Into the Fire: Latin American-US Immigration in the Global Age. A regular contributor to AlterNet, Lydersen is also an instructor for the Urban Youth International Journalism Program in Chicago.

Groups Seek to Close Immigrant Center

Associated Press

Advocacy groups for immigrant families and the Department of Homeland Security are at odds over detention facilities in Texas and Pennsylvania that critics argue are inhumanely housing adults and young children in jail-like conditions.

In a report released Thursday, groups speaking for immigrants demanded the immediate closure of the T. Don Hutto Residential Center north of Austin, the Texas capital, a facility that once was a jail.

The advocacy groups - the Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services - said they based their complaints on visits to these sites by their members and interviews with detainees.

At the Hutto site, their report said, a child secretly passed a visitor a note that read: "Help us and ask us questions," it said. The groups reported that many of the detainees cried during interviews.

"What hits you the hardest in there is that it's a prison. In Hutto, it's a prison," said Michelle Brane, detention and asylum project director for Women's Commission.

At a news conference, the groups charged that some families are kept up to two years in the facilities, with those petitioning for asylum or trying to prove they shouldn't be deported, remaining there the longest.

"We are taking people who fear persecution and locking them up," said Ralston H. Deffenbaugh, president of the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service.

The Homeland Security Department defended the centers as a workable solution to the problem of illegal immigrants being released, only to disappear while awaiting hearings. Also, they deter smugglers who endanger children, said Mark Raimondi, a spokesman for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the DHS division that oversees detention facilities.

"ICE's detention facilities maintain safe, secure and humane conditions and invest heavily in the welfare of the detained alien population," Raimondi said.

White House press secretary Tony Snow said last week that finding facilities for families is difficult, and "you have to do the best with what you've got. "

The Pennsylvania center - the Berks County Shelter Care Facility - has about 84 beds and the Texas facility can house up to 512 people. The groups fear that government will expand detentions in similar facilities.

The facility in Leesport, Pa., about 50 miles northwest of Philadelphia, is a former nursing home and "less jail-like," allowing families to go on field trips and having a better education system for children. But it also has problems, the groups said. It is part of a larger juvenile facility housing U.S. citizens charged with or convicted of crimes and detained juveniles.

The groups suggested that immigration officials release families who are not found to be a security risk, and said the federal government should consider less punitive alternatives to the detention centers, such as parole, electronic bracelets and shelters run by nonprofit groups.

"Unless there's some crime or some danger, families don't belong in detention," Deffenbaugh said. "This whole idea of trying to throw kids and their parents in a penal-like situation is destructive of all the normal family relationships we take for granted." |

| |

|