|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | April 2007 Editorials | Issues | April 2007

Mexican Anti-Pedophile Crusader Puts Her Life on the Line

Manuel Roig-Franzia - Washington Post Manuel Roig-Franzia - Washington Post

| | A bodyguard keeps watch as Lydia Cacho Ribeiro leaves the women's shelter she runs in Cancún, Mexico. Multiple death threats have been made against her. "This is my life," she says. (KAHN) |

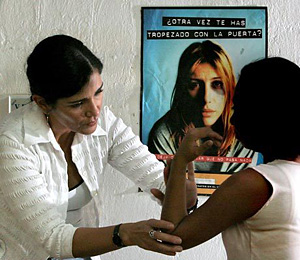

| | At the women's center, Cacho Ribeiro examines a woman hurt in a domestic- violence incident. (KAHN) |

Cancún, Mexico — The bodyguards linger in the steakhouse foyer, conspicuous with their handguns in lumpy fanny packs. The bulletproof SUV sits in quick-getaway position outside.

And now Lydia Cacho Ribeiro's cellphone rings.

"Yes, I got in OK," Cacho says from an out-of-the-way table. "I'm fine."

Cacho sets the phone down with a weary smile.

"He was worried," she says of her longtime partner, the prominent Mexican editor and columnist Jorge Zepeda Patterson. "This is my life."

A crusade against pedophiles has made Cacho, recently honored by Amnesty International, one of Mexico's most celebrated and imperiled journalists. She is a target in a country where at least 17 journalists have been killed in the past five years and that trailed only Iraq in media deaths during 2006.

In the spring of 2005, Cacho published a searing exposé of the child abuse and pornography rings flourishing amid the $500-a-night resorts and sugar-white beaches of Cancún. Her book "The Demons of Eden: The Power That Protects Child Pornography" chronicles in cringe-inducing detail the alleged habits of wealthy men whose sexual tastes run to 4-year-old girls.

The arrest

Her book was just a middling seller, and her fight against child abusers was getting little attention until one afternoon in mid-December 2005 — the afternoon the cops showed up.

On that day, Cacho says, police officers from the far-off state of Puebla shoved her into a van outside the women's center she runs on a crumbling side street. They drove her 950 miles across Mexico, she says, jamming gun barrels into her face and taunting her for 20 hours with threats that she would be drowned, raped or murdered. The police have disputed her version of events, saying she was treated well.

Cacho found herself in police custody because Mexico's "Denim King," textile magnate Kamel Nacif, had accused her of defamation, then a criminal offense. (Inspired by Cacho's case, the Mexican Congress recently passed a law decriminalizing defamation.) Cacho had written that Nacif used his influence to protect a suspected child molester, Cancún hotel owner Jean Succar Kuri, and that one of Succar's alleged victims was certain Nacif also abused underage girls.

Cacho had triggered her car alarm as she was being taken into custody, a predetermined signal to alert her staff to trouble. Friends suspected the men in uniform were only posing as police. E-mails and phone calls zinged from Cancún to Mexico City, and from there to international human-rights groups.

"There was so much fear," recalled Lucero Saldana, then a Mexican senator. "We were thinking there might have been an attempt on her life, that she might have been kidnapped."

Saldana, taking no chances, was waiting when Cacho arrived at the jail in Puebla. She scrambled to arrange bail. But even a fired-up Mexican senator could not save Cacho from a humiliating strip search while a clutch of male officers loitered.

After nearly half a day in jail, Cacho was free on bond, though rattled. She was soon to find out how highly placed her enemies were.

Bombshell tapes

Two months later, tapes started airing on Mexican radio stations, crude male voices spewing obscenities. It was clear the men were talking about Lydia Cacho. The tapes had been delivered anonymously to Mexico City newspaper and broadcast reporters. No one knows who made the recordings.

In one conversation, presumably recorded the day of Cacho's arrest, an unidentified voice tells Nacif to pay "a woman in the jail to rape her."

But the real blockbuster was on another tape.

"My precious governor," Nacif can be heard saying.

"My hero," another voice says.

That second voice was unmistakable. It was Puebla Gov. Mario Marin, a stalwart of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which dominated Mexico for seven decades before losing its grip on the presidency in 2000.

"Well, yesterday, I gave a [expletive] whack on the head to that old bitch," Marin tells Nacif.

Nacif thanks his "precious governor" for ordering Cacho's arrest and says he will send Marin "a beautiful bottle of cognac."

Marin acknowledged that the voice was his, but he said the recordings were taken out of context. His rebuttal had almost no impact. In the court of public opinion, the verdict was clear: Cacho was the victim of influence-peddling and a political vendetta.

Cacho has since persuaded Mexico's Supreme Court to hear a human-rights complaint — the first such case involving a journalist. But in Mexico, where corruption and violence against women are rampant, there have been no repercussions for the central players.

Still, with each new tape, commentators went wild, many calling for Marin's resignation. Satirists went even wilder. Almost overnight, performance artists took to stages to mock the governor, songs were composed and satiric cognac ads posted on the Internet.

"For that very special occasion, to celebrate among friends, arrives the commemorative cognac 'My Precious Governor,' " begins one spoof. "My Precious Governor. So that you can become a good pedophile."

Suddenly, Cacho was everywhere: the evening news, talk shows, newspaper front pages. Nacif and Marin, unwittingly, had made her a star.

Lydia Cacho is 42 years old but looks younger. She keeps fit with a yoga regimen and favors tight jeans, spike-heel boots and plunging necklines.

She also knows she doesn't fit the mold of a feminist expected by the old-style, "machismo"-dominated political system that she says infuriates her for neglecting women.

"They think we're all ugly, fat, mustachioed feminists," said Cacho, who studied humanities at the Sorbonne and speaks four languages. "I don't have to dress like a man to demonstrate that I am intelligent. ... If they have a problem with my attractiveness, with my sexuality, that's their problem."

Cacho's feminism sprouted in the "lost cities" outside Mexico City, the impoverished squatters' hells that developed in the 1960s and 1970s with almost no government regulation. She spent weekends as a child in the lost cities working on homespun social-aid programs with her mother, Paulette Ribeiro Monteiro, an early Mexican feminist who died four years ago.

"Her passion comes from her mother," said Lucia Lagunes, director of a Mexico City news agency that focuses on women's issues. "Her mother taught her to have ideals and to fight for them."

An intense career

In more than two decades straddling activism and journalism, Cacho has run from angry drug dealers waving AK-47s because she sheltered their battered wives. She has been threatened too many times to count. She has held 20 people in her arms as they died, most of them clients of an AIDS shelter she founded.

In 1999, she says, she was raped by a man in a bus-station bathroom.

A friend in the prosecutor's office told her she was probably attacked as revenge for her social work and her newspaper columns. She decided not to pursue the case.

"As a journalist before, I kept writing about the importance of filing reports with the police, and after the rape I learned that the main thing is to recover and to be protected and to be more sensitive to victims of violent crimes," Cacho wrote in an e-mail.

In 2004, a journalist friend asked Cacho to co-write a book about a burgeoning child-abuse scandal in Cancún. A young woman had approached the authorities and said Succar, the multimillionaire hotel owner, had begun abusing her when she was 13. Others, including her sister, also had been molested, the young woman said.

Pointing the finger

Cacho spun an outline in days for a book that would not only allege Succar had abused more than 100 girls, but also accuse him of laundering money for organized crime and of being protected by powerful politicians.

"Are you crazy?" she recalls her friend asking her.

The friend, whose name she keeps secret for fear of repercussions, dropped out. Cacho started writing.

"Demons of Eden" opens with a 13-year-old girl, whom Cacho calls "Cintia," clutching a stuffed animal as she tells a psychologist how Succar — the man she called "Uncle Johnny" — molested her at the age of 8. Afterward, Cintia says, he brandished a knife and threatened to cut her "into pieces." Cacho quotes the girl saying, "He is the devil."

Cacho writes that Succar's victims suffer just as much after they approach authorities. A local prosecutor calls a news conference and distributes photographs of the girls, their addresses, their parents' names and even their cellphone numbers. A school "morals teacher" reveals that she knew about Succar's abuse for years but did nothing about it.

Cacho writes of overhearing a group of male journalists speculating in a smoke-filled room about whether a 12-year-old could enjoy sex and commenting that "old Succar likes young meat."

A key moment comes when Succar's first accuser, whom Cacho calls "Emma" in her book, lures Succar to a Cancún restaurant equipped with a hidden camera set in place by law-enforcement officials. In the video, Succar describes sex with 4-year-old girls as "my vice" and says he knows he is committing a crime.

Armed with such damning evidence, Cacho says, the authorities do nothing, except tip off Succar. The heads-up gives him ample time in late 2003, she writes, to buy a first-class ticket to the United States, where he owns a Los Angeles mansion.

Succar was arrested in Arizona in February 2004 and was extradited last July to Mexico, where he is being held in a maximum-security prison while his case is argued. José Wenceslao Cisneros, Succar's attorney, said in an interview that six of seven accusers have submitted signed affidavits recanting their testimony. He says Emma was not a minor when she had what he calls a consensual relationship with Succar.

"Succar Kuri never abused a minor," Wenceslao says. The tapes, he says, were doctored by law-enforcement officials, whom he accuses of trying to extort $1 million from his client.

Cacho says Succar bribed and pressured his accusers to sign papers recanting their allegations. Emma didn't want to sign, Cacho says, which indicates her abuser still can dominate her.

"It's disgraceful"

It's night in Mexico City and Cacho has slipped away from her bodyguards for a brief and increasingly rare taste of freedom. A waiter spreads shot glasses around the table at La Covadunga, the crowded and smoky hangout of Mexico City intellectuals where the clientele shout to be heard over the slap of dominoes on tabletops.

Some of Cacho's rage at the pedophiles comes from her certainty that they rob victims of normal sex lives as adults. She writes of Emma struggling with sobbing fits when she tries to be intimate. Cintia, Cacho writes, wears four pairs of underwear since being molested by Succar.

Despite Cacho's notoriety, Lagunes, the news-agency director, laments that child abuse still gets little attention in Mexico. The media focus on the political scandal spawned by her case rather than the estimated 20,000 children abused each year in Mexico.

"It's disgraceful," Lagunes says.

Cacho writes in her epilogue that "hundreds of Mexican girls are and continue to be tortured, violated and trained by powerful men to be sold and photographed."

She is at work on a new book, this one focused on the trafficking of women and girls. She whispers that tomorrow she has a meeting with "a really good source." She raises her eyebrows in anticipation and rubs her hands together. |

| |

|