|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | May 2007 Editorials | Issues | May 2007

Mexico’s Journalists Feel Heavy Hand of Violence

Manuel Roig-Franzia - Washington Post Manuel Roig-Franzia - Washington Post

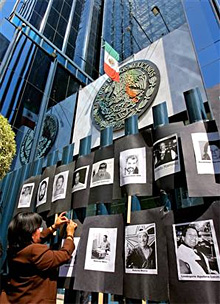

| | A woman sticks pictures of slain or missing Mexican journalists at the entrance of the Attorney General’s Office in Mexico City on World Press Freedom Day, May 3. (Omar Torres/AFP) |

Monterrey, Mexico - Gamaliel López Candanosa seemed an unlikely candidate to join the ranks of disappeared or murdered reporters in Mexico, now the second deadliest country in the world for journalists after Iraq.

Known for his rascal's smile and laughing eyes, López distinguished himself not as a hard-nosed investigative reporter, but as the clown prince of television news in this prosperous industrial city about 130 miles southwest of McAllen, Tex. He slipped into tights, a mask and a cape for his on-air reports, morphing into "Super Pothole Man," a comic book-style hero who joked about poorly maintained streets.

But on the afternoon of May 10 -- after taping a piece that featured him singing with a one-eyed mariachi and reporting live on the birth of conjoined twins -- López and his cameraman, Gerardo Paredes Pérez, vanished. Colleagues at the TV Azteca affiliate where they have worked for 12 years fear the veteran journalists are dead. They suspect drug cartels, which have been blamed for 3,000 murders in Mexico in the past year and a half, and which have turned this once mostly peaceful city into a shooting gallery.

More than 30 journalists have been killed in the past six years in Mexico, including a television reporter in Acapulco and a print journalist in the northern state of Sonora in the month before López and Paredes disappeared. Countless others have been kidnapped in a campaign of intimidation largely attributed to the drug cartels.

As more reporters die, journalism itself is suffering. A newspaper in Sonora said last week that it was temporarily shutting down because of attacks and threats by criminal gangs. Top editors at the two largest newspapers here in Monterrey, Milenio and El Norte, said in interviews that they no longer ask crime reporters to dig deeply on their stories.

"I don't know how to do investigations without getting people killed," Roberta Gomez, Milenio's executive editor, said during an interview at a Monterrey seafood restaurant where gunmen opened fire during the lunch rush not long ago.

At risk is the vibrancy of the free press in Mexico's still developing democracy. President Felipe Calderón has called the intimidation of journalists "an unacceptable situation," promised to protect journalists and discussed possible legislation to achieve that goal. But reporters keep dying and news media offices keep getting attacked.

In the past 15 months, grenades have been thrown into newspaper offices in Cancun, Hermosillo and Nuevo Laredo, and gunmen have attacked a radio station and newspaper in Oaxaca. On Saturday, the decapitated head of a city councilman was left in the doorway of the newspaper Tabasco Hoy in the eastern state of Tabasco.

The threats and violence have sown fear across the journalistic spectrum. While crime reporters are common targets, sportswriters have been kidnapped by drug cartel hit men upset over coverage of their favorite soccer teams. Feature reporters have been kidnapped, too, though the reasons are more mysterious. In the case of TV Azteca, colleagues suggested López might have been targeted because he had boasted about knowing the locations of executions and proudly told a colleague that he had twice been kidnapped -- for him it was a badge of honor.

Monterrey, a city of 4 million at the foot of the soaring, rocky Sierra Madre, once seemed immune to the drug violence roiling Mexico. The nation's third-largest city is routinely ranked as one of the safest places to do business in Latin America and is home to some of the nation's most exclusive residential neighborhoods.

But 2007 has marked a startling reversal. In Monterrey and the surrounding state of Nuevo Leon, more than 100 police officers have been arrested on corruption charges and more than 70 killings have been recorded in the first five months of the year. Calderón has sent federal troops in armored personnel carriers to patrol some streets. Almost all of the murders are attributed to drug cartels, which residents say are attracted to Monterrey for the same reasons others flock here: clean streets, nice neighborhoods, good schools.

‘Great details’

"We know which kids belong to the narcos," a former educator said on condition of anonymity. "They're the ones who show up with all the bodyguards and the fancy cars."

At Milenio, a 40,000-circulation daily, editors began detecting the change about a year ago. One afternoon, a seasoned crime reporter approached Alejandro Salas, one of the newspaper's most experienced crime writers and editors, with a hot story.

"I've got great details," Salas remembers the reporter telling him.

The reporter had plied confidential sources to find out that a member of the local prosecutor's office was in a romantic relationship with a hit man from the notorious Sinaloa cartel. The prosecutor, the hit man and two others had just been murdered, the reporter said.

Salas, who has been a journalist in Monterrey, Tijuana and other Mexican cities for 23 years, smelled a front-page splash, and so did the reporter. But the reporter made one request before sitting down to write, Salas recalled: "Don't sign my name to the story."

Salas was floored. This was the kind of story reporters enter in contests, the hot scoop that makes a writer the toast of the after-deadline watering hole. But instead of grabbing the limelight, the reporter was begging for anonymity.

Around the same time, Salas said, he and other crime reporters were picking up snatches of disturbing chatter on police scanners. Cartels were hacking into police radio frequencies and saying, "I'm following a 20," the numerical code for a journalist. "I'm going to kill a 20."

Soon, other reporters were also asking for their bylines to be removed. With fear rising in the newsroom, Gomez gathered her top editors.

"It's going to get worse before it gets better," Gomez recalled telling them. She issued a decree: no more bylines on crime stories.

"They've intimidated us," Salas said later. "Their messages have had an effect."

Still, Salas did not feel the newspaper was doing enough to protect its staff, especially the 10 or so reporters who focus on crime. Even without bylines, he feared drug cartels could identify reporters who have distinctive writing styles, especially a star writer known for literary flourishes in crime stories. So, Salas instructed editors to rewrite all crime stories in an antiseptic, just-the-facts style.

"It's less fun now," Salas said. "There's less spice, fewer ingredients. There's no literary beauty."

The terror creeping across newsrooms has caused quick and dramatic changes in the ways stories are reported here. Monterrey may be Mexico's most competitive television market, because it is served by two national networks and a slew of local stations. But television reporters who once schemed to beat the competition are now collaborating, hoping for safety in numbers.

"They're going out in pools to cover crime stories, like Nicaragua 20 years ago or Baghdad now," said Alfonso Teja, a veteran television journalist at TV Azteca, where López works.

Less digging

Frequently, journalists here say, they now file crime stories based solely on police reports, without probing deeper. Reporters have to be so cautious that Teja fears Mexican journalism could slide back to the practices of a bygone era -- before Mexico shook off one-party rule in 2000 and began transforming into a true democracy. In those days, Teja said, the old reporters' saying was a version of "see no evil, hear no evil": "In Mexico, nothing happens, and when something happens, still nothing happens."

"Journalists are scared, and the situation is very grave," said Alejandro Gutiérrez, a writer at Mexico City-based Proceso magazine and author of an upcoming book, "Narco-Trafficking: Calderón's Great Challenge." "Information is one of the pillars of democracy."

At El Norte, a 68-year-old newspaper with more than 140,000 subscribers, editors now fuzz out the faces of all police officers in crime pictures -- a practice that is becoming less necessary because officers now often wear ski masks to crime scenes so they cannot be identified by drug cartel photographers.

El Norte reporters, like their competitors at Milenio, no longer put their bylines on stories and seldom try to conduct deep investigations for crime pieces, Eduardo Campos, a top editor at El Norte, said in an interview.

"Journalistic idealism is through," said Campos, who got his start more than 20 years ago writing hard-hitting investigative pieces and uses the "Rocky" movie theme as his cellphone ringer. "We're confronting reality. We've never seen anything like this. The debate is no longer theoretical."

Not long ago, two El Norte journalists -- a reporter and a photographer -- were kidnapped and beaten by drug cartel thugs, then released after several hours, according to newsroom sources. Word of the kidnapping raced through this city's journalism grapevine.

"I was thinking, 'What is happening to my profession?' " a seasoned Monterrey reporter said during an interview after slipping out of a crowded bar for fear of being recognized.

Journalists here anxiously awaited details of the kidnapping. Back in the El Norte newsroom, the journalists who had been kidnapped were terrified about inciting their abductors, a newsroom source said.

The story of their ordeal was never published. |

| |

|