|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | May 2007 Editorials | Issues | May 2007

Relatives of Missing Immigrants Face Lifetime of Wondering

Thelma Guerrero - Statesman Journal Thelma Guerrero - Statesman Journal

| Migrant numbers

The annual average migrant work force in Oregon's agricultural industry is about 58,000 people, which can vary throughout the year.

The figure soars to between 90,000 and 112,000 workers during the peak harvest season.

The season's low point rounds out at about 30,000 workers.

SOURCE: Oregon Employment Department |

Francisco Bustamante was jolted out of bed by the sound of a telephone ringing early on the morning of Aug. 29, 2005. The legal Woodburn resident asked himself: Was he dreaming or hearing things?

A faint but frantic voice on the other end of the line wanted to know whether he had heard from seven family members who were making their way up from Oaxaca, Mexico, to Salem.

The six men and a 14-year-old boy were supposed to call their families upon their arrival at the Arizona-Mexico border, the female caller told Bustamante. But they'd not been heard from since their departure more than a month earlier, and their families were desperate for information, she told him.

Every year, hundreds of illegal crossers like the missing men from Oaxaca risk their lives to make it across the 2,000-mile-long U.S.-Mexico border in search of economic independence.

Some of them head to the Salem area to work in the fields.

Some crossers are caught and sent back to their country of origin.

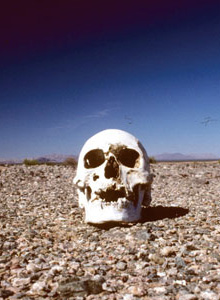

While others make it across without being detected, they're often met by inhospitable deserts, where temperatures can be so hot that shoes can melt right off a person's feet and turn a 180-pound body into a skeleton in a matter of weeks.

What remains are family members who are chained to a lifetime of wondering what could have happened to their loved ones.

Trying his best not to sound worried, Bustamante told the caller that he hadn't heard a word from the men, but said they'd likely arrive in Salem any day.

"The truth is, I was petrified," Bustamante, a cannery worker, said in his native Spanish earlier this spring. "I knew this was not good, but I did what I could to remain optimistic."

What he did was pack his bags and, along with his pal, Pedro Elena Ríos, a Salem resident to whose home the men were headed, took off to the Arizona border to search for their loved ones.

Searching for family

Their first stop was the Consulate of Mexico in Tucson, Ariz.

"Yes, (the searchers) were here," said Alejandro Ramos Cardoso, the consulate's spokesman. "But we had no information for them."

While in Tucson, the pair visited the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol Protection office. Officials with the agency checked a list of names of Mexican nationals being held in an area detention center. But the list yielded no results.

The two men then headed to Nogales, Ariz., after learning from the border patrol that detainees are sent to a holding facility there when no beds are available at the local detention center. But the trip turned out to be futile.

Bustamante and Ríos trekked to the border at Lukeville, Ariz., and Sonoita, Sonora, Mexico. The spot is a popular crossing point for "coyotes," or smugglers who bring illegal immigrants into the United States.

There, they met with foggy minds. Some people thought they had seen the men but weren't sure. Others couldn't recall ever seeing them.

Needing to return to work after several weeks in Arizona, Bustamante and Ríos' last stop was at the Consulate of Mexico in Phoenix, where officials added the names of their loves to a long list of missing Mexican nationals.

"Everything we had saved, we spent looking for our loved ones," said Ríos, a legal resident and native of Oaxaca, who picks strawberries and blueberries in the Salem area. "We're convinced that even if people saw them try to cross the border, the people wouldn't say because they're scared of retribution."

A grim gamble

Early on the morning of July 16, 2005, the six men and one teenager boarded a bus in the fishing village of San Augustín in Oaxaca, Mexico. Their destination was the northern Mexican town of Altar, Sonora, near the Arizona border.

Bustamante said he contacted the bus company in San Augustín where the men had purchased their tickets and boarded the bus.

"Their spokeswoman told me the bus driver reported there had been no problems on the trip to Altar, and that our loved ones were fine when they got off the bus," he said.

No one is known to have seen or heard from the group since.

It's not known where along the border the group had planned to cross into the United States. It's also unclear whether they actually crossed the border.

Bustamante's hunch is that the men went missing somewhere between Altar and Sonoita, Mexico, and Lukeville, Ariz.

"My concern is not immigration (officials)," Bustamante said. "My fear is that Mexican vigilantes or the Minutemen may have captured and killed them. God forbid, no one deserves that."

Deaths in the desert

Heightened security along the Texas and California borders has funneled an estimated 4,500 undocumented immigrants annually into the remote Arizona desert, border patrol officials have said. Most travel on foot.

The perilous journey has led to the deaths of thousands of migrants.

July, the month the group of Oaxacan men would have attempted to cross the border illegally, is typically the hottest in Arizona, when temperatures can climb above 120 degrees.

Since 1999, more than 4,000 people have died along the U.S.-Mexico border, according to border patrol officials. Many died from heat exhaustion and exposure to the cold.

Searches often yield bones and bits of desiccated flesh, relics of the desert's destructive power.

Back to the border

But another equally powerful danger may exist, said Sarah Harkness, the coordinator of the United Methodist Hispanic/Latino Ministry Training Institute in Salem.

"One of our contacts theorized that perhaps (the missing men) are working as indentured servants for a company that may have paid their passage through coyotes and would not be able to leave until they had worked their debt off," Harkness said.

Harkness and other religious leaders from the Salem area invited Bustamante on a pre-planned trip to the Arizona border in October. The leaders went to the border to learn about the root causes of migration to the United States.

While there, Harkness accompanied Bustamante for yet another visit to the Mexican Consulate in Tucson.

It was then the two learned about a new program funded by the Mexican government and run by Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

A chance for closure

The Baylor program involves taking DNA samples from a tooth or a bone fragment of skeletal re-mains found in the desert. The DNA results then are entered into a database at the university. Officials with the various consulate offices then contact families in Mexico who have reported loved ones missing, to request they submit a DNA sample to authorities. Those samples are sent to Baylor, where they're compared with those in the college's database.

Earlier this year, the missing men's family members in Oaxaca were contacted and agreed to give DNA samples in the hope of finding their loved ones, Cardoso said.

"We have not been notified of a match in this case," he said.

Resigned that their relatives are likely dead, Bustamante and Ríos, who recently moved to Alaska temporarily to work, wait to hear news about the men.

"A disappearance is worse than a death," Bustamante said. "With a death there is an end, but with a disappearance there's no closure, you're just left wondering what happened."

tguerrero@StatesmanJournal.com or (503) 399-6815 |

| |

|