|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | May 2007 Editorials | Issues | May 2007

Are Mexican Femicide Cases Being Glossed Over?

Frontera NorteSur Frontera NorteSur

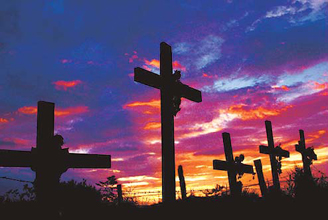

| | City of death: Pink crosses are scattered throughout Juárez, reminders of the more than 300 missing and slain women over the past decade. (OCRegister.com) |

Nearly six years after the discovery of eight murdered young women in a Ciudad Juarez cotton field stunned the world, growing doubts surround Mexican authorities' accounts of the crimes. Two previous cases against alleged murderers unraveled amid revelations of tortured suspects, fabricated evidence, bizarre stories of organ trafficking, misidentified victims, the murders of two defense attorneys, and the suspicious death of one suspect.

Now the Chihuahua Office of the State Attorney General (PGJE), the agency charged with the investigating the crimes, is moving ahead with legal charges against the third round of suspects in the cotton field case.

In an interview with Frontera NorteSur, Chihuahua State Attorney General Patricia Gonzalez contended that three young men from Ciudad Juarez, Francisco Granados, Alejandro Delgado and Edgar Alvarez, embarked on a drug and alcohol-splashed killing spree of young women that began in the 1990s.

While holding that satanic worship could have been a motive in the slayings, Gonzalez denied that the ECCO computer school, which some family members of victims from both Ciudad Juarez and Chihuahua City suspect of involvement in femicide, had anything to do with the Ciudad Juarez crimes.

"This case is more related to street-level drug dealing," Gonzalez said. "These young men worked for an individual who distributed drugs in small quantities in a sector of Ciudad Juarez." Gonzalez declined to name the shadowy drug dealer, adding that authorities are attempting to detain two more suspects in the crimes. Past PGJE spokespersons, including former Special Prosecutor Suly Ponce, denied that drug dealing had anything to do with the women's murders.

Gonzalez charged that the current suspects randomly offered rides to young women on the street, sexually attacking and then stabbing their victims to death before dumping the bodies in the cotton field located across the street from the headquarters of Ciudad Juarez’s Maquiladora Civil Association. Situated in the city’s so-called “Golden Zone,” the cotton field sits in a heavily transited area.

In addition to the 2001 cotton field murders, Gonzalez's office is linking the latest suspects to the Lote Bravo, Lomas de Poleo, and Cristo Negro serial murders that ravaged Ciudad Juarez from 1995 to 2003. All three suspects named by Gonzalez were teenagers at the time of the 1995 Lote Bravo killings. A PGJE power point presentation about the case against Alvarez and his friends includes the names of 1995 murder victims Olga Alicia Carrillo Perez and Silvia Elena Rivera Morales as among the possible victims of the suspects. Initially, the PGJE tied the late Egyptian national Abdel Latif Sharif Sharif to the Carrillo and Morales murders.

Asked if the inclusion of the names of Carrillo and Morales in the PGJE's investigation meant that Sharif was innocent of the crimes, Gonzalez said that because Sharif's case was before her time she had no knowledge of his alleged victims. Maintaining his innocence, Sharif died in a Chihuahua City prison last year while serving a 1995 sentence for the murder of Elizabeth Castro in a conviction critics have challenged.

At a public presentation sponsored by the Santa Fe Rape Crisis and Trauma Treatment Center, held in New Mexico’s capital city on Mother’s Day weekend of 2007, Gonzalez credited various US agencies, including the FBI, for permitting her current murder investigation to proceed. At the time of Edgar Alvarez's arrest in Colorado last summer, Tony Garza, the Bush Administration's ambassador to Mexico, announced a major step forward in resolving the eight murders, and Alvarez was quickly deported to Mexico.

Granados, who is jailed on an immigration law violation in the United States, gave a tape-recorded confession to the Texas Rangers last year that led to Alvarez and Delgado. Gonzalez attempted to play a portion of the confession to the Santa Fe audience but the audio failed to deliver.

"The important thing for us is that this is an investigation that flows from the investigation that North American authorities also are directly realizing," Gonzalez later said in an interview.

"No type of pressure existed. We're working the technical and scientific evidence. Jose Francisco Granados' home produced physical evidence of women's clothing, and other implements including purses, women's shoes, [and] cosmetics. All this is being processed in our forensic laboratory. We even managed to obtain a genetic profile from the Cristo Negro site that we will compare with the genetic profiles of Francisco Granados, Edgar Cruz, Alejandro, and the other two individuals whose detention is pending."

Critics Slam the PGJE's Case

The PGJE's account of the cotton field killing is strikingly similar to the same department's original but later discredited version of how bus drivers Victor Garcia and Gustavo Gonzalez allegedly killed the women. In the original case, Garcia and Gonzalez were accused of randomly kidnapping women, raping their victims and then beating them to death with bats. Both men were allegedly high when they committed the crimes, though toxicology tests contradicted the state's assertions. The basic difference in the latest PGJE case is that the alleged perpetrators supposedly used knives to kill their victims.

Sally Meisenhelder, an organizer for the Las Cruces-based Friends of Juarez Women, a non-governmental organization that has worked closely with victims' families, doesn't give credence to the PGJE's latest case. "It's the same old stuff, and now there is whole new set of scapegoats," Meisenhelder said.

Other knowledgeable sources strongly disputed the PGJE's claims of how the murder victims found in the cotton field were killed.

"The official position is absurd," contended Mexican criminologist Oscar Maynez, who headed the PGJE department that supervised the 2001 examinations of the eight victims. According to Maynez, the decomposed nature of the bodies, many of them just bones, made determining the cause of death difficult.

While investigators found no evidence of stab marks on bones of victims, Maynez told Frontera NorteSur that they detected signs that some of the victims could have been strangled to death, a pattern in scores of other killings. An upcoming report from the highly respected Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, which has spent nearly two years examining the remains of Ciudad Juarez and Chihuahua City femicide victims, is expected to draw similar conclusions.

Maynez quickly dismissed Attorney General Gonzalez's contention that the lack of identifiable stab wounds in the corpses was caused by the way the presumably substance-impaired killers cut into sensitive organs like the heart. "They are saying that these people are better than surgeons," Maynez said. "The (fabrication) of scapegoats is becoming more sophisticated. They are trying to feed the evidence into the story."

Maynez discounted the possibility that Alvarez and his street buddies, who reportedly struggled with drug, emotional, job and marriage problems, had the capacity to hide, transport and then dump numerous bodies over an eight-year period without being detected.

"You are talking about 16-year-old kids, who had no money and were consuming drugs, killing women and somehow [they] didn't get caught," he said. "I'm sure they weren't involved in the cotton field murders."

The former PGJE official added, "US officials have to look closely at this case and not take my word for granted. This is very serious. Behind the murders is a very organized, resourceful structure."

The PGJE's case shows other signs of coming apart. Media reports place key suspect Alvarez in Colorado during many of the women's disappearances and murders attributed to the migrant.

Last February, "protected witness" Alejandro Delgado publicly recanted. Delgado charged that he was physically manhandled, isolated and threatened by Chihuahua state police officers. In statements to Ciudad Juarez reporters, Delgado declared that Granados and Alvarez were both innocent, and that he made up the murder story under pressure from Chihuahua state policemen who had isolated him away from his home.

Almost immediately after making his denunciation, Delgado was arrested by the PGJE and charged with murdering 16-year-old Silvia Gabriela Laguna Cruz in 1998. A judge quickly threw out the charge as baseless.

Gonzalez denied that Delgado was forcibly isolated or slapped with a trumped-up charge for complaining to the press.

"Alejandro Delgado said that he was really afraid of Edgar Alvarez's family and that he wanted to be protected," Gonzalez said. "He was with us a protected witness until his wife got mad and wanted him to go home. In our opinion, Edgar Cruz's defense picked (Delgado) once he got home to get Edgar Cruz off the hook."

Then there is the matter of Francisco Granados’ sanity. The allegedly repentant mass murderer reportedly engaged in unusual behaviors like talking to the devil ever since he was a teenager. While acknowledging that Granados could be lying, Gonzalez affirmed that authorities are conducting tests to determine the truthfulness of the suspect’s statements. Still, Gonzalez was confident that, until now, corresponding evidence has established the “reliability of this man.”

Questions hang over the authorities' version of the alleged randomness of how the victims were selected. Three of the cotton field victims had some sort of relationship with the privately-owned ECCO computer school in Ciudad Juarez, as did several other femicide victims in Chihuahua City to the south, an intercity "coincidence" that has not publicly come up at all in the cases against Granados, Alvarez and Delgado.

Patricia Cervantes, the mother of Neyra Azucena Cervantes, a 2003 Chihuahua City murder victim who worked and studied at the successor institution of ECCO, said in an interview that she has not been questioned by the PGJE about any possible connections between her daughter’s murder and the cotton field case. Cervantes expressed surprise at the state’s current case, adding that she has not seen any news of the prosecutions in the Chihuahua City media.

If the official version of the cotton field crimes is correct, it means that numerous victims who came into contact with ECCO, a minuscule educational institution operating in a population pool of more than 2 million persons in two different places, somehow wound up in the clutches of serial killers in different places and at different times from early 2001 to early 2003. Several years ago, ECCO spokesmen denied any involvement in crimes to the border-region news media.

Pinning the murders on Alvarez and company closes the door on other possible suspects in the serial killings, including police officers. A 2003 US State Department cable about the Cristo Negro slayings, obtained via the Freedom of Information Act by Keith Yearman, an assistant professor of geography at DuPage University in Illinois, noted the lingering suspicions of official complicity in the femicide.

"Authorities report they are following several investigation leads, including one of possible police involvement in the disappearances, but no progress has been reported," stated the cable.

Yearman, who is waiting to receive documents from the FBI, said that a similar request for documents from the US Central Intelligence Agency related to the cotton field case and other women’s slayings in Ciudad Juarez was turned down on national security grounds.

US Support Shores Up the PGJE

Claiming no party affiliation, Patricia Gonzalez was elected to her post in a 2004 multi-partisan vote by the Chihuahua State Legislature. The former judge has enjoyed a good rapport with sectors of the women's and human rights communities. At the Santa Fe forum, Maria Pilar Sanchez, director of Ciudad Juarez's Casa Amiga rape crisis center, praised Chihuahua’s state attorney general for "doing things" and bringing "transparency" to the scene.

Gonzalez's office is undertaking an ambitious legal and police training reform program in Chihuahua, planning, for example, to institute oral trials for the first time. However, the legal case against the cotton field suspects is proceeding in the traditional fashion of written statements constituting the weight of evidence.

Gonzalez’s legal reform efforts are encountering resistance from members of the old legal establishment who are criticizing both the speed and character of the reforms.

In Santa Fe, Gonzalez insisted that she is purging the PGJE of bad elements, but charged that her campaign is complicated by persistent corruption in the Federal Agency of Investigations, Federal Preventive Police, and Ciudad Juarez Municipal Police.

Gonzalez confirmed to Frontera NorteSur that she has received death threats, specifically in connection to the investigation of men's homicides, but has not suffered "any threats" in relation to the femicide probes.

US support is a cornerstone of Gonzalez's efforts. A US$5 million grant from the US Agency for International Development is underwriting much of the reform project. The Washington, D.C.-based firm Management Systems International (MSI) manages the grant. According to the non-profit Center for Public Integrity, MSI is a privately owned foreign aid contractor that runs programs in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other nations.

Only days after Edgar Alvarez was deported to Mexico last year, Ambassador Garza appeared in Ciudad Juarez, where he praised Attorney General Gonzalez and Chihuahua Governor Jose Reyes Baeza for opening a new forensic laboratory and "implementing a new criminal justice system that is transparent and fair, that protects human rights."

Ambassador Garza's words contrasted with the US State Department’s internal discourse just a few years earlier. The State Department cables obtained by Yearman reveal that US authorities were fully aware of multiple episodes of torture, corruption and killings attributed to PGJE personnel.

Assisted by the USAID funding, US border states are contributing to the PGJE's makeover. Gonzalez's office, for example, has signed a training and legal cooperation agreement with the New Mexico Office of the Attorney General. In the run-up to the Santa Fe forum, the New Mexico AG's office released a press statement noting the gravity and cross-border significance of the femicide.

So far, the New Mexico-Chihuahua agreement doesn’t include joint field investigations. New Mexico Assistant Attorney General Maria Sanchez-Gagne told Frontera NorteSur that no one from her office, to the best of her knowledge, is involved in the cotton field investigation. Sanchez-Gagne would not comment on past incidents of violence and criminality involving PGJE agents, but defended the cross-border reform program underway between New Mexico and Chihuahua.

“What I do know is that Chihuahua is moving forward to change its criminal justice system,” Sanchez-Gagne said. “They are the first state to do this in Mexico, and we are applauding them and assisting them to make this a more secure city and state.”

A Border Femicide End Game?

Convictions of Edgar Alvarez and his friends in the cotton field case and other women’s murders could well mark the end game in many of the Ciudad Juarez femicide [investigations]. High stakes exist for the PGJE, Patricia Gonzalez, Mexican human rights guarantees, and US Mexico policy, not to mention the accused suspects, victims' families and society in general.

On the international level, non-governmental human rights organizations, the European Union, the United Nations, the United States Congress, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) have all clamored to one degree or another for justice. In the United States, the murders are likely to get renewed attention when the movie Bordertown, which stars Jennifer Lopez and Antonio Banderas, is released to commercial theaters later this year.

According to attorney Adriana Carmona of the Chihuahua City-based Women's Human Rights Center, relatives of seven Ciudad Juarez and Chihuahua City femicide victims are pursuing cases against the Mexican government for human rights violations in the IACHR. While the IACHR's recommendations are purely advisory, lawyers for victims' families are studying the possibility of taking the cases to the next level, to the Costa Rica-based Inter-American Court for Human Rights, which issues obligatory orders to member countries, including Mexico.

Four of the IACHR cases involve women that Alvarez and crew are officially suspected of killing, but convictions of the current suspects could help block or slow international legal action. If the critics are on the mark, convictions of Alvarez and his old buddies will mean that the real killers of women would once again go unpunished.

Already, Mexican law guarantees impunity in a growing number of the femicide cases. As the Washington Post noted in a recent article, Mexican law has a 14-year statute of limitations on murder. The newspaper mentioned several murders from 1993 whose prosecution time has passed. On a campaign stop in Ciudad Juarez last year, then-presidential candidate Felipe Calderon vowed to end impunity in the women’s killings.

Meanwhile, sectors of the Mexican government, media and industry are taking steps to wipe the memory of the cotton field and other serial crimes, still legally unsolved, from the public consciousness. Ciudad Juarez's identity as an industrial border magnet that constantly draws new people to the city even as older residents leave for the United States helps facilitate erasure.

Recently, the Office of the Federal Attorney General quietly withdrew police officers it had long assigned to guard the cotton field. DuPage University's Yearman finds irony in the pending relocation of the US Consulate to a site close to the cotton field in Ciudad Juarez's "Golden Zone." The relocation promises a bonanza for new businesses like hotels that serve thousands of visa-seekers. "The (cotton field) is going to be plowed over so we can expand the US diplomatic presence in Mexico," Yearman observed.

Additional Sources: Washington Post, May 14, 2007. Article by Manuel Roig-Franzia. El Paso Times, July 28, 2006; August 18 and 22, 2006; September 7 and 12, 2006. October 1, 2006. Articles by Diana Washington Valdez, Louie Gilot and Tammy Fonce-Olivas. Norte, September 10, 14 and 28, 2006; February 23, 2007. Articles by Carlos Huerta, Ignacio Alvarado Alvarez and Javier Arroyo Ortega. El Diario de Juarez, February 22 and 23, 2007. May 16, 2007. Articles by Armando Rodriguez, Martin Orquiz, Juan de Dios Olivas, and Sandra Rodriguez Nieto. El Universal/EFE, March 5, 2007. Aserto (Chihuahua City), March 2007. Article by Ignacio Alvarado Alvarez. Denver Post, August 17 and 20, 2006. Articles by Michael Riley, Allison Sherry and editorial staff.

Frontera NorteSur (FNS)

Center for Latin American and Border Studies

New Mexico State University

Las Cruces, New Mexico

Frontera NorteSur is a free, on-line, U.S.-Mexico border news source. FNS can be found at http://frontera.nmsu.edu/) |

| |

|