|

|

|

Editorials | May 2007 Editorials | May 2007

Mexico and the American Dream

Rosa Martha Villarreal - Dailynews.com Rosa Martha Villarreal - Dailynews.com

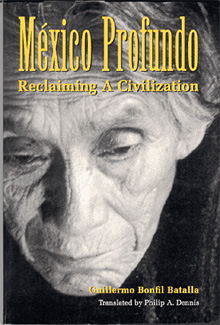

| M้xico Profundo

Reclaiming a Civilization

by Guillermo Bonfil Batalla (Translated by Philip A. Dennis)

University of Texas Press, Austin: 1996, 1998 (pp. 198)

Check it out at Amazon.com |

Perhaps it is only appropriate to begin a conversation about the future of illegal immigrants in America with a reference to the Mexican anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla and his insights about what constitutes a "civilization project." Appropriate because it is not lost on the American public that it's our neighbor Mexico that has made the most significant contribution to this population, and because Mexico's recent nationalistic rhetoric has aroused skepticism, fear, and contempt in the American public.

A prominent argument among the fiercest opponents of normalization of this illegal population - or, to use a politically incorrect term, amnesty - is that Mexican nationals constitute a threat to the very core of what it means to be an American. This is where Professor Batalla's definition provides a provocative point for discussion.

When Batalla coined the term "Mexico profundo," he divided the national consciousness in terms of a nationalistic, political project - which began when Mexico declared its independence from Spain, replete with all of the symbolism of a nation-state - and the other Mexico, composed of the spirit and aspirations of its native peoples and their worldview. This, said Batalla, was the true collective soul, the true nation, uncorrupted, real because it has been dreamed, and stifled by the machinations of the political system.

Ironically enough, one can say that there, too, is an American equivalent to this world of the profound. Except that, reflecting the character of Americanism, the definition evolved not from the intelligentsia, but from the soul of the people, the descendants of immigrant peasants: The American Dream.

As a loyal American of Mexican descent, I take personal offense at the misappropriation of this cherished concept by extremists and special-interest groups in America, misguided Mexican intellectuals, and cynical Mexican government officials. I am annoyed with the aforementioned folks because they regard the American Dream as the equivalent to an employment agency.

As I remind my students at the college where I teach, the American Dream was and is the fulfillment of the desire that the individual could be free to aspire to his most profound desires regardless of his background, bloodlines, and pedigrees. The American Dream is the Jeffersonian trust in the wisdom of the people, not the ruling class, and certainly not the intelligentsia, who, although well-meaning, are frequently so disconnected from the lives of common men and women that their concern is perceived as patronizing, and correctly so.

The American Dream is the elevation of the individual over the group. Though one's past is an integral part of one's identity, the manner in which one's ethnic identity is recalled is ultimately the spiritual project of the individual.

For example, my parents were born in Mexico and immigrated (yes, legally) in 1954. Being well-versed in the history of both countries, I consider the conduct of my country (U.S.A.) in the Mexican-American war to be less than honorable. However, I harbor neither resentments nor irredentist desires.

This is the spiritual aspect of the American Dream: I can create my own identity and shape my own convictions and not be beholden to traditionalism or group-think. Regrettably, the position voiced by both the Mexican government and members of the Mexican intelligentsia is that because my parents were born in Mexico, my loyalties and interests should lie with Mexico. My creative fascination with Mexico, yes; my political loyalties, no.

Which brings me back to the initial problem facing the American body politic: What to do with the millions of men and women and their children living illegally in America? Should we give them amnesty? Perhaps that is the only humane and workable solution. But this is the opportunity for the body politic to articulate what it means to be an American versus an American citizen.

To be an American is to embrace the America that is desired and dreamed. The American Dream signifies the freedom to define, create, and if necessary, re-create the self.

Perhaps what is most frustrating to me in this debate about illegal immigration is that people of Mexican descent have been cynically defined as a group rather than individuals. How ironic.

Rosa Martha Villarreal is the author of "Chronicles of Air and Dreams: A Novel of Mexico" and "The Stillness of Love and Exile." |

| |

|