|

|

|

Travel Writers' Resources | May 2007 Travel Writers' Resources | May 2007

Mexican Journalists Decry Weak Efforts Against Violence on Peers

Oscar Avila - Chicago Tribune Oscar Avila - Chicago Tribune

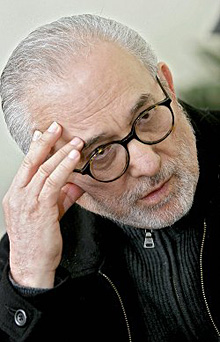

| | Mexican journalist Jesϊs Blancornelas at his Zeta weekly's office in Tijuana, Mexico. The journalist, who died Nov. 23, 2006 in Tijuana at the age of 70, dedicated himself to exposing drug trafficking activity and had survived an attempt to murder him in 1997. He lived constantly under escort since that occasion. (Omar Torres/AFP) |

Mexican journalists have grown impatient as more of their colleagues are murdered, kidnapped or threatened because of their work. Increasingly, the media have directed their frustration toward the office designed to provide them justice: the Special Prosecutor for Crimes Against Journalists.

Created amid fanfare in 2006 by then-President Vicente Fox, the office is now seen by many media organizations as a toothless entity without the resources or political will to successfully prosecute crimes committed against journalists.

The sense of urgency increased this month after the fatal shooting in Acapulco of Amado Ramirez, a reporter for Televisa, Mexico's largest television network. Ramirez was shot weeks after airing an investigation on drug traffickers, and his slaying prompted hundreds of journalists to rally for greater protections.

On Wednesday, the Vienna-based International Press Institute reported that Mexico's seven murders in 2006 made it the second-deadliest nation for journalists, behind Iraq. Media watchdogs said the violence is tied to warring drug cartels, often in league with corrupt police, who hope to intimidate journalists from reporting their activities.

In his first interview with the foreign press, Special Prosecutor Octavio Orellana defended his office's accomplishments but acknowledged he could use more personnel. Orellana said he often has to borrow investigators from the attorney general's office because his budget is modest.

"I am satisfied that the work is being done, but I am not satisfied because we would always want more results," said Orellana, a lawyer and criminologist who assumed the post in March. "Like everything in life, if you have more human elements, a larger budget, you think you can do more."

A problem for decades

Journalists have been under siege for decades, especially near a U.S. border region that remains a trouble spot. Just last week, the body of journalist Saul Noe Martinez of the newspaper Interdiario was found wrapped in a blanket after he had been kidnapped from a town along the Arizona border.

Journalists hailed the creation of the special prosecutor's office as recognition that the violence had become a national crisis. But political analyst Jorge Zepeda said the move created a false sense that the Mexican government took the problem seriously.

"The prosecutor was created by Fox as a demagogic, rhetorical attempt to lower the pressure in the public over the violence against journalists," said Zepeda, a former editor at newspapers in Mexico City and Guadalajara.

Jose Antonio Calcaneo, a newspaper editor in the city of Villahermosa, complained that President Felipe Calderon has not been any more willing than Fox to take on the issue. Calcaneo has seen the threats up close. An investigative reporter at competitor Tabasco Today, Rodolfo Rincon, was kidnapped in January, reportedly after receiving threats.

"Calderon declared himself against this wave of violence, but in his deeds, this has translated into nothing. Absolutely nothing," said Calcaneo, president of FAPERMEX, a national federation of media organizations. "They have practically made the special prosecutor disappear."

Calcaneo also said Orellana, the special prosecutor, has "shirked his responsibility" by not staking out his jurisdiction over crimes against journalists.

Orellana said he prefers to hand over cases in which journalists appear to have been victims of organized crime to SIEDO, an arm of the attorney general's office that investigates those groups. In defending his performance, he also noted that many cases remain at the state level and never make it to his office.

Without giving details, Orellana said his office could close some cases soon.

Orellana said he would support making crimes against journalists automatic federal cases. He said many reporters are threatened because they are investigating state authorities, and that the public generally has more confidence in the integrity of federal prosecutors.

Shared blame

Carlos Lauria, Americas program director at the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists, said the special prosecutor has not achieved any "breakthrough results," but he blamed a generally "dysfunctional" justice system. Lauria noted progress in some investigations and said a federal prosecutor still was an improvement over state authorities, who often are corrupt or inefficient.

Some colleagues of Ramirez, the slain Acapulco reporter, have complained that state investigators in Guerrero have botched the probe. Two men were arrested days after the killing but were released on bail.

Orellana said his office will push efforts to prevent, not merely prosecute, crimes against journalists. Staffers are training reporters how to preserve threatening e-mails and text messages that could be used later in criminal prosecutions, for example. About half of the office's 68 investigations in 2006 involved threats.

In another move welcomed by journalists, Mexican lawmakers and Calderon pushed through a law this month that effectively removed criminal penalties for slander and libel. Media organizations had complained that government authorities used charges to squelch investigative reporting.

Still, analyst Zepeda worries that journalists will continue censoring themselves if they think authorities cannot guarantee justice. The media's importance to Mexico's developing democracy makes the special prosecutor's work even more important, Zepeda said.

"It doesn't mean that a journalist is more important than a breadmaker or taxi driver," Zepeda said. "But behind every murdered journalist are hundreds of journalists who will stop talking about organized crime. The damage caused to Mexican society is immense."

oavila@tribune.com |

| |

|