|

|

|

Editorials | Issues | June 2007 Editorials | Issues | June 2007

Ex-Surveillance Judge Criticizes Warrantless Taps

Michael J. Sniffen - Associated Press Michael J. Sniffen - Associated Press

go to original

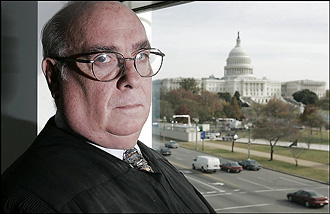

| | U.S. District Judge Royce C. Lamberth |

A federal judge who used to authorize wiretaps in terrorism and espionage cases criticized yesterday President Bush's decision to order warrantless surveillance after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

"We have to understand you can fight the war [on terrorism] and lose everything if you have no civil liberties left when you get through fighting the war," said Royce C. Lamberth, a U.S. District Court judge in Washington and a former presiding judge of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, speaking at the American Library Association's annual convention.

Lamberth, who was appointed to the federal bench by President Ronald Reagan, expressed his opposition to letting the executive branch decide on its own which people to spy on in national security cases.

The judge said it is proper for executive branch agencies to conduct such surveillance. "But what we have found in the history of our country is that you can't trust the executive," he said.

"The executive has to fight and win the war at all costs. But judges understand the war has to be fought, but it can't be at all costs," Lamberth said at the Washington Convention Center. "We still have to preserve our civil liberties. Judges are the kinds of people you want to entrust that kind of judgment to more than the executive."

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which Lamberth led from 1995 to 2002, meets in secret to review applications from the FBI, the National Security Agency and other agencies for warrants to wiretap or search the homes of people in the United States in connection with terrorism or espionage cases. Each application is signed by the attorney general. The court has approved more than 99 percent of such requests.

Shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks, Bush authorized the NSA to spy on calls between people in the United States and terrorism suspects abroad without warrants. The administration said that it needed to act more quickly than the surveillance court could and that the president has inherent authority under the Constitution to order warrantless domestic spying.

After the program became public and was challenged in court, Bush placed it under court supervision this year. The president still asserts the power to order warrantless spying.

White House spokesman Tony Fratto said Bush believes in the program, which is classified because its purpose is to stop terrorists' planning.

The program "is lawful, limited, safeguarded and - most importantly - effective in protecting American citizens from terrorist attacks," Fratto said. "It's specifically designed to be effective without infringing Americans' civil liberties."

Lamberth took issue with Bush's approach.

He said the special court, established by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, met the challenge of reacting quickly to the Sept. 11 attacks. Lamberth was stuck in a carpool lane near the Pentagon when a hijacked jet slammed into it that day. With his car enveloped in smoke, he called marshals to help him get into the District.

By the time officers reached him, Lambert said, "I had approved five FISA coverages [warrants] on my cellphone." He also approved other warrants at his home at 3 a.m. and on Saturdays.

"In a time of national emergency like that, changes have to be made in procedures. We changed a number of FISA procedures," Lamberth said.

Normal FISA warrant applications run 40 to 50 pages, but in the days after Sept. 11, the judge said, he issued orders "based on the oral briefing by the director of the FBI to the chief judge of the FISA court."

Lamberth would not say whether he thought Bush's warrantless surveillance was constitutional. "Judges shouldn't give advisory opinions, and I was never asked to give an opinion in court," he said.

But, he said, when the NSA briefed him about the program, he advised the agency to keep good records so that, if any applications came to the FISA court based on information obtained from the warrantless surveillance, the court could rule on the legality.

He said he never got such an application.

Bush, Senate Head for Showdown on Domestic Spying

Reuters

go to original

Washington - President George W. Bush headed toward a showdown with the Senate over his domestic spying program on Thursday after lawmakers approved subpoenas for documents the White House declared off-limits.

"The information the committee is requesting is highly classified and not information we can make available," White House spokesman Tony Fratto said in signaling a possible court fight.

The Senate Judiciary Committee approved the subpoenas in a 13-3 vote following 18 months of futile efforts to obtain documents related to Bush's contested justification for warrantless surveillance begun after the September 11 attacks.

Three Republicans joined 10 Democrats in voting to authorize the subpoenas, which may be issued within days.

"We are asking not for intimate operational details but for the legal justifications," said Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, a Vermont Democrat. "We have been in the dark too long."

Authorization of the subpoenas set up another possible courtroom showdown between the White House and the Democratic-led Congress, which has vowed to unveil how the tight-lipped Republican administration operates.

Last week, congressional committees subpoenaed two of Bush's former aides in a separate investigation into the firing last year of nine of the 93 U.S. attorneys.

Bush could challenge the subpoenas, citing a right of executive privilege his predecessors have invoked with mixed success to keep certain materials private and prevent aides from testifying.

Bush authorized warrantless surveillance of people inside the United States with suspected ties to terrorists shortly after the September 11 attacks. The program, conducted by the National Security Agency, became public in 2005.

Wartime Powers

Critics charge the program violated the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which requires warrants. Bush said he could act without warrants under wartime powers.

In January, the administration abandoned the program and agreed to get approval of the FISA court for its electronic surveillance. Bush and Democrats still are at odds over revisions he wants in the FISA law.

"The White House ... stubbornly refuses to let us know how it interprets the current law and the perceived flaws that led it to operate a program outside the process established by FISA for more than five years," Leahy said.

Interest in the legal justification of the program soared last month after former Deputy Attorney General James Comey testified about a March 2004 hospital-room meeting where then-White House counsel Alberto Gonzales tried to pressure a critically ill John Ashcroft, then the attorney general, to set aside concerns and sign a presidential order reauthorizing the program.

With top Justice Department officials threatening to resign, Bush quietly quelled the uprising by directing the department to take steps to bring the program in line with the law, Comey said.

Leahy noted that when Gonzales, now attorney general, appeared before the panel on February 6, he was asked if senior department officials had voiced reservations about the program.

"I do not believe that these DoJ (department) officials ... had concerns about this program," Leahy quoted Gonzales as saying. Leahy added, "The committee and the American people deserve better."

Additional reporting by Matt Spetalnick. |

| |

|