|

|

|

Editorials | July 2007 Editorials | July 2007

Argentina's Struggle to Restore the Rule of Law

Sam Ferguson - t r u t h o u t Sam Ferguson - t r u t h o u t

go to original

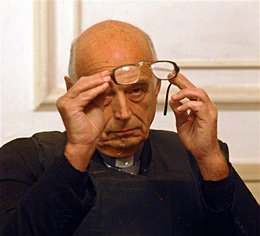

| | Former police chaplain, Christian Von Wernich, is seen during a hearing in a federal courthouse in La Plata, Argentina, Thursday, July 5, 2007. Von Wernich, who was arrested in 2003, is the first Roman Catholic cleric to be prosecuted on charges of complicity in deaths and disappearances during Argentina's 1976-83 military dictatorship. (AP/Daniel Luna) |

La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina - The trial of a former Argentine military chaplain accused of crimes against humanity began on Thursday under heavy security. The trial may be a tipping point for Argentina's long-awaited reconciliation process after their seven year "dirty war."

Military chaplain Christian von Wernich faces charges of crimes against humanity for his role in Argentina's "dirty war," when as many as 30,000 people were disappeared by the military government between 1976 and 1983. Von Wernich has been indicted as an accomplice in seven counts of murder, 41 counts of deprivation of liberty and 30 counts of torture. Von Wernich refused to answer to any of the charges on advice of his lawyers.

Security has been high since the star witness in the first case to go to trial - Julio Lopez - was disappeared ten months ago. Lopez provided the key testimony against Miguel Etchecolatz, the former Buenos Aires province police chief who was recently sentenced to life in prison on numerous counts of murder, torture and forced disappearance. Human rights groups suspect police, or former police, sympathetic to Etchecolatz and other military officials now being prosecuted, were involved in the incident as a way to chill future witnesses from testifying. Carlos Rozanski, president of the tribunal hearing the case, has promised security will be high. This is the same tribunal which tried the case against Etchecolatz. Carlos Zaidman, who will testify later this month against von Wernich, said, "Witnesses must not be intimidated by Lopez's disappearance. We have a compact with Lopez. The truth must come out, justice must be served."

Von Wernich appeared in Court under heavy guard. He was in handcuffs as three guards in flack jackets and one with a riot shield accompanied him into the courtroom from a back entrance. In court, he was cut off from the public by a pane of bullet-proof glass. His priest's collar stuck out above the neck of his body armor. Von Wernich was shuttled from his prison cell in Marco Paz to La Plata late last night to avoid possible retributive attacks against him.

"We have fought for 30 years against impunity. We have waited and waited. This is an important step in uncovering the truth and bringing the dictators to justice" said Hayedee Gastelu from Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a human rights group composed mainly of mothers of the disappeared. The Madres have marched through Plaza de Mayo, the historic square of public protest outside the Government House in Buenos Aires, every Thursday since 1977, demanding the government investigate the disappearance of their children.

Several dozen Madres, who are easily identified by their white headscarves embroidered with the names of their children and the date they disappeared, sat in the first two rows of the courthouse. Most still are uncertain about the whereabouts of their children, though they are presumed to be dead. "We come because we need to know the truth. The state must condemn these acts of genocide. We come to support the other mothers and the process," said Nora Decortiñas, also from Madres, whose son Carlos disappeared on April 15, 1977. She wore a picture of him around her neck.

Von Wernich's case is just the second to proceed to oral trial since the Supreme Court overtured a series of amnesty laws from the late 80s - enacted in response to significant military pressure - that shielded prosecution of most crimes committed during the dictatorship. It is the first case ever to proceed against a member of the Catholic church, which is widely suspected of having supported the military government. "This case is central to finding out what happened under the dictatorship with all sectors of society. Business, the church, many were complicit. This can begin the discussion," says Myriam Bregman, lawyer for Justicia Ya which is representing many of the victims and the victim's families in this case. Von Wernich served as military chaplain to former Buenos Aires police chief Ramón Camps, who was convicted of crimes against humanity shortly after the collapse of the military government, but was later pardoned - along with all of the other accused and convicted at the time - by former President Carlos Menem in 1990.

The day's events were devoted to procedural matters. A clerk for the court read the government's accusation and von Wernich's defense, which amounted to over 100 pages and took four hours. Just after lunch, the tribunal called von Wernich into the witness chair. Because Argentina's criminal procedures are based in the civil law tradition, witnesses and the accused face the three-judge tribunal, which asks the majority of the questions. The tribunal took von Wernich's information, read the accusation to him and asked him if he would respond to questions from the tribunal. At one point, chants of "murderer" from protesters outside temporarily interrupted the proceedings while von Wernich was on the stand. Von Wernich refused to respond to any further questions on advice of his lawyers, and returned to his seat.

The accusation against von Wernich centers on his participation at five clandestine centers throughout Buenos Aires Province. Von Wernich is accused of using his position as a priest to solicit information from the detained. After torture sessions, von Wernich would allegedly appear and ask the detained for information, telling them their souls would be saved if they would give up the information he was looking for. In one incident, von Wernich reportedly told a prisoner, "The life of men depends on God and your collaboration." As one victim commented, "This torture was worse than physical pain; it was psychological torture, which was much harder to deal with."

In the most grave charge, von Wernich is accused of accompanying seven men to Buenos Aires's municipal airport where he knew the men were to be beaten and killed, though the men thought they were being released. Von Wernich allegedly acted as a "spiritual adviser" to the dirty warriors, assuring them that the fight was just and God would absolve them.

The defense is resting its case on pastoral privilege. They claim, first, there is no direct evidence that von Wernich tortured or murdered anyone; and, second, any associations he had with the victims in this case was in a spiritual capacity, functioning as a priest. Von Wernich claims he took testimony from everyone as a religious figure, soldiers included. Because of his pastoral privilege, he claims he was not obliged to say or release what he heard in confession.

Among von Wernich's suspected victims is Jacobo Timmerman, former editor of the newspaper La Opinion, whose disappearance became internationally known after his family instigated a successful habeas corpus action. Timmerman later wrote a book, "Prisoner without a Name, Cell without a Number," which helped precipitate the collapse of the Junta.

After the collapse of the dictatorship, von Wernich was forced from his position as priest in La Plata after massive public pressure. The Catholic church, however, never investigated his role in the dictatorship. Von Wernich moved to Chile for 14 years, where he lived under an assumed name, Christian González. The church could not be reached for comment.

In the days to come, over 100 witnesses will be called. Oral testimony will take place Mondays and Thursdays. Testimony is expected to last until mid-September.

The trial was made possible by a ruling by the Supreme Court which overturned a series of amnesty laws and presidential pardons issued in the late 80s and 1990 after the collapse of the dictatorship. At that time, the military still held significant power within Argentina and the laws were enacted in an attempt to consolidate the democratic transition by quieting military unrest. After two decades of pressure, however, the Supreme Court overturned the amnesty laws in 2005.

Within the next month, the court is expected to annul the presidential pardons granted in 1990, which freed all who had been accused of crimes against humanity, and stopped all trial proceedings against military officials. Since the amnesty laws were overturned, the government has initiated investigations into nearly 1,000 crimes committed by the military government during the war.

Sam Ferguson is a JD candidate at Yale Law School and a former senior researcher at the Rockridge Institute under George Lakoff. He is investigating the problems of transitional justice and democratic consolidation after periods of military rule. He is currently living in Buenos Aires. |

| |

|