|

|

|

Editorials | January 2008 Editorials | January 2008

True Voice of the Revolution

Ed Vulliamy - The Observer Ed Vulliamy - The Observer

go to original

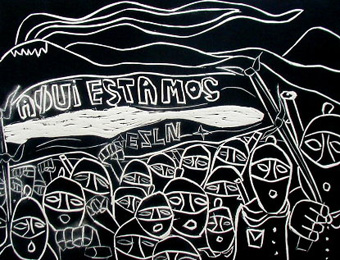

| | Miguel Cuanalo, Aqui Estamos (Zapatistas) | | |

While the media spotlight shone on Europe and the US, hundreds of protesters were massacred on the streets of Mexico. Why is it still the forgotten story of '68?

The great spectacle of 1968, and capitalism's closest shave, came in Paris. The victory, in the end, belonged to Prague. The severity of 1968 in Rome and Berlin begat years of armed insurrection, while in Chicago, flower power grew up and got serious about war in Vietnam. But the bloodbath of 1968, the detonation of a revolutionary battle that rages still, came in a place that many accounts of that year reduce, inexplicably, to a footnote: Mexico.

Historians write of the black gloves held aloft by medal-winning American runners at the Mexico Olympics. They write less about white gloves worn by the Olympia Brigade of the Mexican army, tanks behind them and helicopters aloft, which fired on students, families and workers in the Tlatelolco neighbourhood of Mexico City on 2 October, a week or so before the Games, slaughtering an estimated 350 people. The bodies - if they were not dumped into the sea - are still being disinterred.

The massacre changed Mexico, cracking the system it was intended to preserve at all costs, and ensuring that the legacy of revolutionary 1968 would be more enduring there than anywhere else in the world.

Since the election of President Gustavo Diaz in 1964, Mexico had been through two entwined changes: rapid economic development and the consolidation of an extreme form of centralised government called El Desarrollo Estabilizador (the Stabilising Development) by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) which had ruled since its formation in 1929. Mexico, though not a dictatorship, was a country in which power was exercised secretively, vertically and without a cogent opposition. The bestowing of the Olympics was seen as a recognition of its emergent modernity, and the Games were to be accompanied by cultural and political events organised by President Diaz.

New wealth for some was accompanied by political frustration, and a glimpse of radical idealism from abroad combined with a sudden explosion of domestic causes: the rights of indigenous people, the liberalisation of education, a movement for trade unions independent of the PRI. The confrontation between these yearnings and Diaz's inflexibility was like a hammer on an anvil, producing what Enrique Krauze, 1968 activist and now editor of the magazine Letras Libres, calls a 'luminous and terrible experience, the Mexican '68'.

The great Mexican essayist Octavio Paz explains in his classic book The Labyrinth of Solitude that Mexico 'lacked the orgiastic and near-religious tone of the hippies', but the flavour of the government response was established early, at the end of July, when the Mexican army responded to a student protest by firing bazookas into the old gates of a high school, and occupying it. At a subsequent demonstration, the slogans changed to include 'Unete, pueblo!' (People, join us!) and 'Ganar la calle' (Win the streets) - as the face of Che Guevara, hero of the Cuban revolution, became ubiquitous. In August a strike by schools and universities was organised and the students began to leave their schools, fanning out into the barrios and factories. By the end of August their demands had mushroomed into a mass movement calling for the democratic transformation of Mexico.

Troops had sealed off the university campus, Ciudad Universitaria, and parents, workers and peasants joined the marches by hundreds of thousands, one of them on the vast Zocalo, which commemorates the first Mexican revolution of 1910. For Diaz and the government, the march on 27 August was an encroachment on sacred ground, a defiant claim to the legacy of the Mexican revolution of which Diaz saw himself as guardian. Troops backed by tanks moved in to remove a crowd of 3,000 - a horrific echo of Prague only days before.

On 18 September the army occupied the Ciudad Universitaria. Mexico City was effectively in a state of siege, and the stage set for the massacre at Tlatelolco.

A vivid and poetic account of these weeks was written by Paco Ignacio Taibo, who, in his book entitled simply '68, describes a 'wild and melancholy tango of life' propelling events. Student revolutionary brigadistas found themselves no more than the kernel of ever-expanding concentric ripples of public uprising, comprising their parents, reformists, women's groups, slum-dwellers, workers, and peasants in from the countryside.

The global forest fire of revolution in 1968 needed no internet - if anything, it was the antithesis of the sedentary, logged-in, blogged-out world of today's deactivated youth. It was a time of direct communication, between countries and within them, so that throughout the Mexican summer mimeographs worked all night to produce 'wall newspapers' telling of prisoners, police brutality, and proposed further agitation. Slogans were spray-painted on buses, handbills thrown from tower blocks and leaflets placed inside brown bags alongside bread sold by bakeries.

What Taibo calls 'Radio Rumour' became the only place to learn the truth, as the media submitted itself to government lies. 'Only Radio Rumour knew about the killings in Tlatelolco,' wrote Taibo, 'telling us that the dead had been laid out in the hangar in the military part of the airport, telling us too of the flight over the Gulf of Mexico from which the bodies of murdered students were tossed into the sea. Only Radio Rumour counted the victims and gave them names. '

Tlatelolco was the world nadir of 1968 - a last stand by the student movement and its supporters. The mixed but mainly poor neighbourhood initially forced a withdrawal by the authorities, and thousands had swarmed in to defend it. By the morning of 2 October tanks had surrounded the square in which some 10,000 had assembled. The mood was good, morale high, when suddenly the white-gloved Olympia Brigade opened fire. Their assault was backed by troops, then by attack helicopters fitted for warfare, then the tank rounds. After the massacre the area was sealed, street lights extinguished, phone wires cut and ambulances refused admission until the evidence - apart from the carpet of blood seen by some - was removed. As the first of 2,000 athletes arrived for the Olympics, the protest movement was stunned, and for the moment defeated. But it never went away, and Mexico was never the same again.

'The deeper meaning of the protest movement,' says Octavio Paz, is 'the revelation of that dark half of man that has been humiliated and buried by the morality of progress: the half that reveals itself in the images of art and love.' In Mexico, this march of 'progress' had been fast and sharp, depositing many in a 'marginal position, either permanently or temporarily'. And Mexico's revolution, coming as it did in a 'developing' country rather than industrialised France or north America, occupies an extraordinary place between that in Prague and that in the West, separate from but combining both.

Among the singularities of Mexico '68 was the fact that the figure of Che Guevara and the Cuban revolution, though universals across 1968, were genetically and geographically closer to Mexico than elsewhere. Fidel Castro's revolutionaries had, after all, sailed aboard the Granma from Mexico's shores a decade before 1968 - though Castro failed to lift a finger in support of Mexico '68 or any of its descendants, presumably for cynical fear of losing his air communication hub to Latin America through Mexico City, courtesy of the Mexican government.

Paz aligns the Mexican revolution closer to those in Eastern Europe than in the high temples of Western capitalism. He writes: 'Its closest affinities were with those in the latter [East European] countries: nationalism, reacting not against Soviet interventionism but against North American imperialism'.

Indeed, 'Vive Mexico' and 'Mexico! Libertad!' were to the fore among the slogans of the day, and after one march to the Zocalo students sang the national anthem, claiming it back from the regime on behalf of the Mexican revolution of 1910. The entwining of patriotism and revolution remains to this day: leaflets and posters urging a 'Second Mexican Revolution' began circulating in June 1968, and they still do.

Mexico '68 continues, unlike any other '68. As everywhere else, the Sixties had a profound effect on society in general, and in Mexico they emboldened, ironically perhaps, a new young middle- and business class, which saw the PRI's 70-year tenure come to an end with the election of a former Coca-Cola executive Vicente Fox as president in 2000. But like a riptide beneath the PRI and its successors, the revolutionary current of Mexico's '68 remains strong. After the movement peaked and was crushed, only to be followed by another massacre at Corpus Christi in 1971 (by which time the mastermind behind Tlatelolco, interior minister Luis Echeverria, had become president), its leaders went deep into the Mexican interior to ignite rebellions elsewhere. The most exuberant was that by the 'Zapatista' movement, or EZLN, under Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente - better known as 'Subcomandante Marcos'. In the Nineties he mustered a paramilitary force behind a convergence of causes including agrarian reform, indigenous rights and revolutionary Guevarism. The movement was so popular it won international rock-star status for its leader and semi-autonomy in swathes of the Chiapas region under control of the guerrillas. Since 2002 a further wave of insurgency has crashed across the Oaxaca region, inspired directly by 1968. And recently a mysterious force calling itself the Revolutionary Popular Army has emerged, careful to claim no casualties as it bombs oil pipelines.

This refusal of the Mexican '68 to wither also infuses mainstream politics with energetic radicalism, and led to the founding of the Party for Democratic Revolution which, under its leader Andrés López Obrador, came to within a hair's breadth of defeating the conservative candidate Felipe Calderón in the 2006 election (Obrador claims the result was rigged). For Mexico to be won by the left, ending Uncle Sam's uncontested influence at the Rio Grande, would be a catastrophic development for the US, as the gyre turns across Latin America from the fascist military juntas of two decades ago to widespread social democracy.

There is an especial energy in the Mexican radical movement, a mix of harsh determination and idealism - in part born of Tlatelolco - in a land where it is often difficult to know where the bottom is, where Aztec lore had it that after sunset a 'Black Sun' illuminates the underworld. On the 20th anniversary of 1968 Taibo wrote: 'Where do victory and defeat begin and end? Where was the point of no return? Sixty-Eight seems not only to have ensconced itself in the nostalgia factory within our minds... but also to have produced the epic quantities of fuel needed to power 20 years of resistance. It has stiffened the spines in a land of submission and a hundred times placed in our mouths the words "No!" and "Fuck it!"' |

| |

|