|

|

|

Editorials | Opinions | January 2008 Editorials | Opinions | January 2008

2008: Latin America's Hope and Challenge

Laura Carlsen - Center for International Policy Laura Carlsen - Center for International Policy

go to original

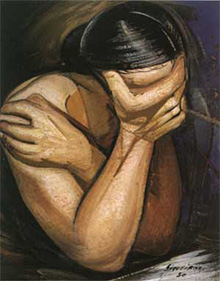

| | David Alfaro Siqueiros, Angustia | | |

It's becoming a platitude to refer to Latin America as the region of hope, and from here in Mexico the perception is tempered by a reality that looks more ominous than hopeful. Throughout Latin America, attempts to build more just and peaceful societies have met with a thousand obstacles, both internal and external.

But what has rightfully captured the attention of the world is that there are efforts at real change in the hemisphere. And "hope" is not defined by guaranteed success, but by belief in an animating vision.

In the 21st century Latin America has produced more than its share of individuals, organizations, and even governments that hold new animating visions. Many have bucked the system in the most literal sense to seek different and better ways of living together, living with the environment, and living in the world.

A few examples from our archives over the past year illustrate the point.

1. Via Campesina: With its upbeat slogan to "globalize hope," its broad international and independent base, and its campaign for food sovereignty, Via Campesina has been setting a new agenda from the grassroots that has already changed the terms of debate and will no doubt gain new ground over the coming year. It may seem strange to envision an organization of small farmers - a sector squeezed from all sides by the forces of globalization - as a harbinger of change. But Via Campesina, with its 149 member organizations in 56 countries, stands on a long history of innovative community projects and autonomous organization.

Following a Via forum in Mexico city this summer we noted: "As globalization erodes community, threatens the quality and accessibility of our food supply, and destroys ecosystems, small farmers are the ones defending these values. In doing so, they hold important keys to the future survival of the planet and rebuilding the kind of society we want for our children."

2. Bank of the South: International finance institutions like the World Bank and the IMF have been discredited in many Latin American countries due to the ruinous consequences of their neoliberal economic prescriptions. The Bank of the South is an attempt at regional cooperation to create a real alternative for development financing. As it takes shape, the new bank faces its share of conflicts of interests. Two stand out: the complex negotiations between large and small countries on vote and contributions, and the debate between orthodox economic interpretations of its role and social priorities. But as Raϊl Zibechi points out, "The new bank offers the benefits of escaping the financial controls exercised by developed countries and capital markets," as well as "fulfilling the needs of the peoples and those who have historically been excluded."

3. The Andean Challenge: Ecuador and Bolivia are undergoing profound changes that offer hope to nations throughout the world. The current governments in both countries established Constituent Assemblies to reform their constitutions to assure greater political equality and fair redistribution of wealth and resources. They face tremendous obstacles as they go up against vested interests and begin institutional reforms. In Bolivia, the reforms seek to break down structures of oligarchic economic power and racist political power that have been adapted since colonial times to maintain elite control. The Assembly concluded amid tense and ongoing conflicts and the constitution now goes to a popular vote. In Ecuador, the assembly and its working groups are still at the stage of gathering proposals and building consensus. As we wrote recently, "The effort to use the state to retake and redistribute resources ceded to private economic interests under globalization, to enfranchise indigenous populations, to narrow the appalling gap between the haves and have-nots of our era deserves a chance and will no doubt provide lessons for the rest of the world."

Other examples of the Andean challenge to top-down globalization come not from governments but from the day-to-day battles in communities. Following the example of the Cochabamba "Water War," Ecuadorians in Guayaquil have organized to demand the right to water and return to public control. Although new governments have opened up historic opportunities for change in the region, it continues to be the grassroots movements that will drive this process.

The Challenges

Along with the hope, come challenges - particularly for those concerned with U.S. foreign policy in the region. Three challenges come to mind, not because they are the most transcendent, but because they are viable and reasonable - and we cannot conceive of a constructive and coherent policy in the hemisphere without these first steps.

1. Engagement with Cuba.

After years of failure in Cuba and in the international arena and an eroding base of domestic support, it's hard to imagine what it would take to change the block-headed U.S. policies toward Cuba. In their article, Center for International Policy analysts Wayne Smith and Jennifer Schuett point out that in 2008 there may be light at the end of the tunnel.

A new president willing to seriously assess and reform the current travel ban and economic embargo, along with a responsible Congress, could break the stranglehold of Cold War ideology and move toward constructive engagement. Already signs have appeared to indicate that current measures to isolate the island and intervene internally could soon fall from favor. The authors write that "There is hope that the changing political equation in Miami, pressure from economic interest groups interested in trade and investment, and support by the majority of Americans for normalization of relations with Cuba will lead to a long overdue policy change after the 2008 elections."

2. Defeat the U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement.

Democrats in Congress have vowed to defeat this agreement due to concerns about human and labor rights violations in Colombia and the government's ties to paramilitary forces. The Bush administration, however, counts Colombian president Alvaro Uribe as its most important ally in the region and has vowed to fight for the FTA.

If today Colombian labor leaders organizing in Coca-Cola and other foreign firms are assassinated to maintain "business as usual," it's likely the situation will get worse when the country is locked into an FTA-model of development that stakes the national economy on foreign investment. The militarization of Colombia as a result of U.S. aid under Plan Colombia has empowered repressive military and paramilitary forces and distanced Colombia from its Latin American neighbors who criticize its allegiance to northern interests and fear "spill-over" of the violence into their territory. The FTA is seen as divisive by other Andean nations.

In the U.S. Congress there is a growing call for a moratorium on all Free Trade Agreements until a full assessment of their economic, political, and social costs has been made. The U.S.-Colombia FTA should be blocked as part of rethinking trade policy, and as a stand against the violation of human rights in that country.

3. Reject Funding for Plan Mexico.

Although $500 million appears a paltry sum compared to military intervention in Iraq and the Middle East, binational relations between the two neighbors with a fractious border would take an ugly turn if the so-called "Merida Initiative" were approved. Also known as Plan Mexico, this program for "regional security cooperation" would provide money and equipment to the Mexican military, police, and intelligence services. None of the aid contemplated in this first package of a $1.5 billion-dollar deal goes where it's most needed, such as addiction prevention and rehabilitation or development financing - and much of it is downright dangerous.

Sending equipment to the Mexican police and military in the context of unprosecuted human rights violations empowers impunity. Increased intelligence-gathering with expanded powers and insufficient protections puts the civil liberties of the general population at risk. The physical presence of U.S. military companies such as Blackwater doing training and equipment maintenance, and direct U.S. involvement in Mexican security could lead to a proxy relationship that compromises national sovereignty and subordinates a traditional Mexican foreign policy of neutrality to a U.S. interventionist foreign policy. Plan Mexico, with its emphasis on interdiction in the drug war, anti-terrorist measures to confront an international threat that does not demonstrably exist in Mexico, and the reinterpretation of immigration as organized crime, corresponds to a logic that heightens violence on all fronts and strains binational relations. Mexico needs and deserves U.S. support, but not to impose regional militarization.

There are many more sources of hope and challenge. They might seem novel to those who just recently felt the new winds blowing from the southern part of the hemisphere, but all are built on years of citizen involvement and vision. U.S. policies can promote rather than suppress these efforts at self-determination and social justice. And there are signs that the United States is ready for that kind of change too.

Laura Carlsen (lcarlsen(at)ciponline.org) is Director of the Americas Policy Program (www.americaspolicy.org) of the Center for International Policy. |

| |

|