|

|

|

Editorials | Opinions | February 2008 Editorials | Opinions | February 2008

Nafta Is a Sweet Deal, So Why Are They So Sour?

Eduardo Porter - NYTimes Eduardo Porter - NYTimes

go to original

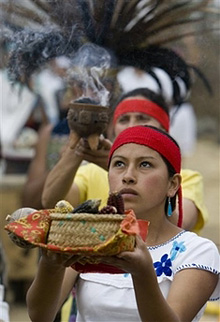

| | A woman holds up a basket containing corn as an offering during an Aztec ceremony to ask for protection for the Mexican corn in Mexico City, Saturday Feb. 9, 2008. The ceremony was organized to protest against the removal of import tariffs on farm goods from U.S. and Canada, as agreed by the North American Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA, timetable. Mexican farmers complain they won't be able to compete with U.S. farmers who can sell cheaper products because they receive government subsidies. (AP/Eduardo Verdugo) | | |

Fourteen years after Nafta came into effect, the last remaining barriers to agricultural trade in North America were dismantled last month. Mexican corn farmers and American Big Sugar hate this unreservedly.

Last week, tens of thousands of poor Mexican farmers marched down Mexico City’s fancy Paseo de la Reforma demanding that Nafta be reversed, their cows and donkeys occasionally taking a nibble from the grass along the median strip. Florida’s sugar barons sent their lobbyists to Capitol Hill.

This shared outrage underscores how egalitarian free trade is: undermining inefficient producers who survive behind protective barriers, be they fabulously wealthy sugar producers in Florida or campesinos on tiny plots in Michoacán.

But despite their shared fears, the two sides of this divide will be affected by Nafta in very different ways. American sugar barons are right to be afraid. Free trade in sugar within North America will allow cheaper Mexican sugar to flood in, undercutting the government system of sugar supports, which guarantees farmers high prices and costs consumers about $1.5 billion a year. Mexico’s rural poor, even if they don’t believe it now, are likely to come out ahead.

Mexican farmers fear that a flood of cheap agricultural imports from the United States will take away their meager livelihoods, and end a centuries-old way of life revolving around small-scale farming of corn. Nafta has already shaken up Mexican farming — mostly for the better. The value of agricultural imports from the United States has doubled since 1994, when tariffs started to gradually decline. Imports of corn have more than doubled by volume.

But this isn’t displacing Mexico’s small-scale farmers. Most corn from the United States is used for feed and doesn’t compete with white corn farmed in Mexico. Mexican corn production is about a third higher than before Nafta came into effect. And cheap American corn is providing cheap feed to Mexico’s livestock farmers.

Mexico confronts a daunting challenge in dealing with rural poverty. One in five Mexicans depends on agriculture, and of those, a third live in extreme poverty. But farming corn on tiny plots will not provide the solution.

The Mexican government must revamp its own system of supports that now favors mainly big farmers, and provide small farmers with access to credit and know-how. Rural Mexico needs investment to increase yields and move out of corn and into more lucrative crops that are better suited to the country’s arid and mountainous terrain. And Nafta will help, providing a market for Mexican agricultural exports.

America’s sugar barons have been pressing hard to stop the opening of Nafta’s sugar trade. They first cut a deal with Mexico’s sugar barons that would have created a new system limiting trade in sugar and other sweeteners — a direct refutation of Nafta’s spirit and rules. Last week, the sugar lobby announced that it was dropping that idea. Yet the sugar support system is still in place in the United States — which means the government may have to start picking up the tab — and the fight isn’t over.

Opening up the sugar trade with Mexico will be good news for Americans: it will lead to lower sugar prices for everybody, from confectionary manufacturers to regular consumers. And Nafta will be good news for Mexico’s consumers and many of its farmers.

The political fight in Mexico isn’t over either. While the government will have to help some of its farmers adapt to a more competitive world, its main agricultural challenge is to keep food prices low to feed a growing urban population. It will also need to help more rural Mexicans find jobs outside agriculture. On all these fronts, Nafta is likely to help. |

| |

|