He Gave Voice to the Right

The London Times The London Times

go to original

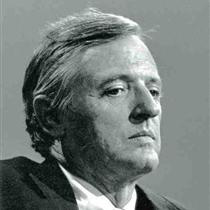

| | William F. Buckley inspired the U.S. right, influencing politicians from Barry Goldwater to George W. Bush. | | |

William F. Buckley was a progenitor, and the best known proponent of modern American conservatism. He founded and edited National Review, the U.S.'s foremost conservative journal; his column, "On the Right," appeared in hundreds of newspapers; his weekly television program, Firing Line, was shown from coast to coast. Handsome and witty, he was a tireless debater and lecturer.

Mr. Buckley, who died yesterday at age 82, wrote at least one book a year - lively political essays, fragments of autobiography, memoirs of sailing and travelling, and then a series of thrillers. His was the urbane voice that accompanied the progress of thorough-going conservatism from the political wilderness to the election of Ronald Reagan to the White House; the legacy of his ideas continues to exert a powerful influence over the administration of George W. Bush.

William F. Buckley Jr. was born in 1925, in New York, the sixth child of William Frank and Aloise Buckley. His father, a Texan, had made a considerable fortune from Mexican and Venezuelan oil. His mother came from an old New Orleans family.

Their natural conservatism had been vigorously reinforced when, in 1921, Mr. Buckley Sr. was expelled from Mexico and his property seized by a revolutionary left-wing government. He, though, was by no means an establishment character, which, Mr. Buckley Jr. afterwards mused, might account for the fact that none of his 10 children showed any inclination to rebel against their father's political views or staunch Roman Catholicism. One of Mr. Buckley Jr.'s liberal opponents referred to the Buckleys as "kind of sick Kennedys," an analogy accepted with characteristic good humour. "Our family plays touch football, too," said Bill, "but not so ferociously."

After graduating as head of his class from Millbrook School, New York, he studied briefly at the University of Mexico, before being drafted into the U.S. army. After being discharged in 1946, he went to Yale, where he studied political science, economics and history.

He was a big man on campus, belonging to the best clubs, touring with the debating team, editing the Yale Daily News and being chosen, in 1950, as class orator for Alumni Day. His proposed speech was rejected by university authorities because he attacked Yale and its professors for their doctrinaire liberalism and atheism. A publisher to whom he described the incident encouraged him to turn the speech into a book. God and Man at Yale, published in 1951, launched Mr. Buckley's career.

In it, he named offending professors and inveighed against what he considered their brainwashing techniques, arguing that the alumni had reason to feel betrayed. The wrath it provoked was amazing; Mr. Buckley was described as "the most dangerous undergraduate ever to attend Yale."

His sister, Priscilla, had been at Vassar, where she detected similar leftist tendencies. Mr. Buckley met, and in July 1950 had married her classmate, Patricia Taylor, of Vancouver.

After a few months working undercover in Mexico for the CIA, he became associate editor of The American Mercury, a journal sadly diminished from the great days of H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan, but he soon resigned in favour of freelance writing and lecturing. With Brent Bozell, who was with him at Yale and had married his sister, Patricia, he wrote another book to outrage the liberals, McCarthy and His Enemies (1954). In it they attacked the U.S.'s anti-anti-communists. They argued that there had been genuine penetration of society by communists, but seemed not to appreciate that senator Joe McCarthy's scattergun approach was much more harmful than helpful to the anti-communist cause.

The U.S. lacked any journal of right-wing opinion, comparable to The Nation and The New Republic on the left. In 1955, he launched National Review, a weekly - afterwards bi-weekly - magazine of political comment and opinion, with arts and review sections to be a platform and a debating ground for sophisticated conservatives.

Although only a third of the money came from family sources, it was agreed that Mr. Buckley should have absolute control of the voting shares, a provision allowing him to prevent the ideological schisms that had destroyed similar journals in the past. Rallying to this new masthead came such theoreticians of the right as Russell Kirk, Frank S. Meyer, Whittaker Chambers and James Burnham. They shared a strong anti-communism - several of them had once been communists themselves - but in their domestic policy, they formed two recognizably distinct, and to some extent incompatible, schools. On one hand were the traditionalists, whose Burkean doctrine emphasized continuity, order and Christian morals. On the other were libertarians, who believed in a minimum of state interference and control.

These schools complemented each other, but could never quite merge. As a group, American conservatives were formulating their position almost from scratch. Despite some indigenous elements (a strict interpretation of the constitution, for example), there was no historic party line for them to follow, so they drew heavily on British and European ideas.

Mr. Buckley himself was neither the best writer nor the most original thinker, but he conducted the group brilliantly. In ferocious clashes, he separated National Review conservatism from two, at that time influential, factions - the "objectivists," led by Ayn Rand, who preached a doctrine of atheistic selfishness, and the John Birch Society, led by Robert Welch, which was obsessed by the notion of communist conspiracy. Ayn Rand would never afterwards stay in a room with Mr. Buckley, and the John Birchers deluged National Review with hate mail.

The liberal establishment had responded to the appearance of National Review with a degree of venom that seems incredible now. Mr. Buckley was compared to Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin and the Ku Klux Klan. As he wrote in an early issue of the magazine, "Liberals do a great deal of talking about hearing other points of view, but it sometimes shocks them to learn that there are other points of view."

He began writing his own column in 1962. Before long, it was being syndicated to 300 papers, and in 1967, received a Best Column of the Year award. In 1966, he started a weekly television show, in which he interrogated, and courteously disputed with, studio guests, including George H.W. Bush, Jimmy Carter, Barry Goldwater, Henry Kissinger, the Dalai Lama, Groucho Marx, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Ian Smith and Margaret Thatcher. When asked why Robert Kennedy had refused to appear, Mr. Buckley replied "Why does baloney reject the mincer?"

Mr. Buckley toyed with practical politics. In 1960, he helped to organize Young Americans for Freedom as a counterpart to the left-wing Students for a Democratic Society. In 1961, he was instrumental in founding the New York State Conservative Party. Beneath its banner, his brother, James Buckley, was elected senator and William himself ran for mayor of New York - primarily as a spoiling operation against the liberal Republican, John Lindsay. When asked what he would do if he won the election, he said: "Demand a recount." He wrote one of his best and most entertaining books about the campaign, The Unmaking of a Mayor (1966). In 1973, he was invited to serve on the U.S. delegation to the United Nations, an experience that proved very disappointing, because he was never allowed to make the speeches attacking the Soviet Union's record on human rights. However, another acidly amusing book, United Nations Journal, came out of it.

Surprisingly, in 1976, he was persuaded to try his hand at fiction - a spy thriller, Saving the Queen, which featured a hero, Blackford Oakes, a CIA man who had been at an English public school and at Yale, with obvious resemblances to the author. In that first, most extravagant and exuberant volume, Oakes enjoys a love scene with "Queen Caroline" of England.

Mr. Buckley's fame was indeed extraordinary. He received literally dozens of honorary degrees and awards. But his charm and modesty in dealing with all manner of people were unimpaired. This frenetic activity - writing in planes and cars and hotel rooms, constantly travelling to lecture and for Firing Line - generated money with which to subsidize National Review. The magazine sold well for that kind of journal, but had never covered its costs. Regular donations from loyal readers, including Ronald Reagan, John Wayne and Charlton Heston, helped.

A younger team was introduced in the late 1980s, but Mr. Buckley remained editor-in-chief, finally giving up control in 2004.

In a sense, though, the job had been done. American conservatism had permeated the mainstream of politics. Mr. Buckley was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1991.

Mr. Buckley's personality, even more than his thinking or his writing, gave impetus, shape and colour to the whole conservative movement. As the columnist George Will observed: "Before there was Ronald Reagan there was Barry Goldwater, and before there was Barry, there was National Review, and before there was National Review there was Bill Buckley with a spark in his mind."

His wife, Pat, died in 2007. He is survived by his son, the author and satirist Christopher Buckley.

No cause of death was given, though Mr. Buckley suffered from emphysema.

How Conservatives Remember Their Giant

'He influenced a lot of people, including me. He was so articulate and he captured the imagination of a lot of folks because he had a great way of defining the issues. It was erudite and yet a lot of folks from different walks of life could understand it.'

- President George W. Bush

'It's this simple. No Buckley, no conservative movement.

- Jack Fowler, Publisher, National Review

'William F. Buckley was, in large measure, the architect of the modern conservative movement. His intellect, wit, and dedication have inspired generations.'

- John Boehner, House Republican leader

'Great man, great leader. Great conservative ahead of his time, articulate and entertaining.'

- Senator John McCain |