|

|

|

Travel Writers' Resources | February 2008 Travel Writers' Resources | February 2008

Mexico is Refuge for World's Persecuted Writers

Chris Hawley - USA TODAY Chris Hawley - USA TODAY

go to original

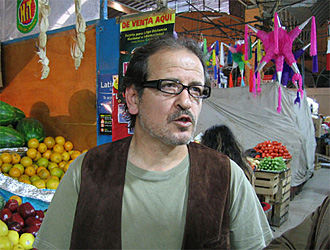

| | Xhevdet Bajraj, a poet from Kosovo, talks about coming to Mexico while visiting a market near his house in Mexico City on Feb. 11. (Chris Hawley/USA TODAY - Arizona Republic) |

| | Koulsy Lamko, a writer from Chad, reads poetry during a presentation at a Mexico City shelter for persecuted writers from around the world, on Feb. 7. (Chris Hawley/USA TODAY - Arizona Republic) | | |

Mexico City — When the paramilitaries burst through his door, beat him and pointed a Kalashnikov rifle at his chest, poet Xhevdet Bajraj knew it was time to get as far from Kosovo as possible.

It was 1999, NATO bombs were falling on the province, and Serbian troops were fighting pitched battles with Kosovo's ethnic Albanian guerrillas. Serbian gunmen were torching homes and locking up anyone who might be perceived as a leader — even semifamous poets. Bajraj joined the thousands of refugees streaming into neighboring Albania.

Then came a strange invitation from a most unlikely place. Mexico City had just opened a "safe house" as a refuge for a persecuted writer. Bajraj and his family were welcome to live there, city officials told him.

And so, shell-shocked and tired, carrying no possessions except two packs of cigarettes, Bajraj became the first of a string of writers given shelter in the Citlaltépetl Refuge House, a renovated mansion in a leafy neighborhood of the world's second-largest city.

"I feel like I was reborn in that house," Bajraj said. Now a naturalized Mexican citizen, he lives nearby and teaches poetry at a Mexico City university.

Since opening in 1999, the refuge has housed writers under threat in Burma, Egypt, Chad, Algeria and Serbia. The refuge is now in talks to host a writer from Iraq, director Philippe Ollé-Laprune said.

They're part of a long tradition of writers who have found refuge elsewhere in Mexico City, from Colombian Nobel Prize winner Gabriel García Márquez to American Beat writer William Burroughs, a fugitive from U.S. drug charges.

Support of government, people

"We have a history of taking in these kinds of people, and they have enriched us as a city," said Isabel Molina, director of cultural relations for Mayor Marcelo Ebrard.

Since the refuge opened here, three other programs have been founded in the United States — in Las Vegas, Pittsburgh and Ithaca, N.Y. — plus several others in Europe.

Few are as active or receive as much government support as the Mexico City house, said Richard Wiley, director of the Las Vegas program. The energy of Mexico City's 20 million people is uniquely inspiring to writers, he said.

The refuge sits in the middle of Condesa, a Mexico City neighborhood settled partly by refugees from the Spanish Civil War and Jews fleeing the Holocaust. The home was built in 1938 by a Spanish exile.

On a recent evening, about 60 people filled the parlor as the current resident, Boubacar Boris Diop of Senegal, and former resident Koulsy Lamko of Chad presented a new book criticizing French foreign policy on Africa.

As the guests sipped wine afterward in the house's soaring anteroom, Lamko confessed he had a lot on his mind. Rebels stormed Chad's capital in early February, and Lamko had not heard from his family in 10 days.

A poet and playwright, Lamko has spent 25 years in exile because of his criticism of Chad's government. In 2003 he was invited to two refuges — one in Norway and the one in Mexico City.

He chose Mexico because of the warmer weather, but he says he found the people to be equally warm. Mexicans are more curious about Africans than Europeans are, Lamko said, and he learned Spanish by fielding questions from inquisitive taxi drivers.

"Here I'm not lost," he said. "In Europe I would feel lost."

Now settled permanently in Mexico, he teaches drama at several universities and is trying to open an African cultural center.

The refuge is the creation of former mayor Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, son of Lázaro Cárdenas, the Mexican president who threw Mexico's doors open to the first Spanish refugees in the 1930s.

In 1998 the younger Cárdenas declared Mexico City a "City of Refuge" for intellectuals at the urging of the International Parliament of Writers, a group headed by British author Salman Rushdie. Rushdie spent years in hiding after Iran's supreme leader issued a religious edict calling for his death in 1989.

The city bought the two-story house, which was in bad repair. The top floor was turned into apartments, while the rest of the mansion was converted into classrooms, an auditorium, offices and a restaurant. The refuge publishes a literary journal, and residents are invited to contribute. The writer gets a stipend and health insurance.

"The idea is to be a literary center, not just a refuge," Ollé-Laprune said. "But we let the residents decide how involved they want to be. Some of these people are coming from bad situations, and if they just want to be left alone, that's fine."

A tribute to Mexico

For some, the refuge becomes a steppingstone. Egyptian Safaa Fathy, a writer and filmmaker, now teaches at Cornell University. Algerian Yasmina Khadra has become a successful novelist and lives in France. Diop is taking a job at Rutgers University in September.

Bajraj's first impression of Mexico City was a riotous mix of pastel-colored buildings, sidewalk food vendors, people and noise.

Yet Kosovo still haunted Bajraj and his family. He said it was months before he could sleep without worrying that someone would break into the house to kill them. (Last week Kosovo formally declared its independence from Serbia, prompting protests in Belgrade.)

For weeks after Bajraj arrived in Mexico City, he sat at his computer, unable to write. Eventually the words came. His first book containing poems written in Mexico, The Liberty of Horror, won Kosovo's top literary prize. Since then he has written five other books.

Bajraj's first book of poems written in Spanish will come out next year. He calls it a way of repaying the country that took him in.

"When I came to Mexico I was dead," he said. "And here I started to live again."

Hawley is Latin America correspondent for USA TODAY and The Arizona Republic. |

| |

|