|  |  |  Editorials | Opinions | July 2008 Editorials | Opinions | July 2008

Remembering the Black Power Protest

Geoff Small - guardian.co.uk Geoff Small - guardian.co.uk

go to original

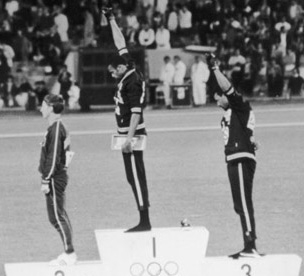

| | Tommie Smith and John Carlos protest with the Black Power salute. (Hulton Archive/Getty) | | |

At the Beijing Olympics, the time is ripe for athletes to pick up the human rights baton from Tommie Smith and John Carlos.

Though mention of their names would draw blank expressions from most people, we all owe a great debt to Tommie Smith and John Carlos. The American sprinters made history when they mounted the Olympic victory stand and thrust their clenched, black-gloved fists into the night sky over Mexico City, on October 16 1968. Their "Black Power" protest produced front page headlines around the world. Not to mention one of the top 10 iconic poster images of the last century.

Perversely, however, the raw iconography of the gesture has helped to obscure its impact and significance. For starters, while the gesture was redolent of the militant Black Panthers, it was actually a plaintive cry for civil rights. Indeed, the athletes were figurehead members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, a non-violent student organisation that transposed racism in sport into the civil rights agenda.

Even so, Smith and Carlos's quiet act of defiance resonated every bit as much as the litany of violent interludes which marked 1968 as an apocalyptic year – the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the Tet offensive, student riots in Paris, and the massacre of hundreds of Mexican student protesters a few weeks before the games.

At the international level, their demonstration gave the lie to the idealistic notion that politics and sports should not mix. It also exposed the hypocrisy inherent in the American administration's racist policies towards black people. Until then, the white political elite had expected black athletes to deliver national glory abroad while regarding them as little more than "fast niggers" at home. Indeed, when OPHR still cherished hopes of organising a black Olympic boycott, its mantra was: "Why run in Mexico only to crawl at home?"

Smith and Carlos's stand was one of several similar black protests at the games. Collectively, these displays pushed the issue of black athletes' rights onto the agenda of the United States Olympic Committee. They forced the athletic authorities to meet OPHR's demands for the employment of black coaches and officials. Ironically, the first black person appointed to the Usoc executive was the legendary Olympian Jesse Owens, who was quickly dispatched to quell any repetition of Smith and Carlos's protest. But his meeting with the remaining black athletes – Smith and Carlos having been sent home in disgrace – culminated in his being branded an "Uncle Tom" and sent away in tears.

Smith and Carlos's legacy is a proud one. All the same, it is one that cost them dearly. Although they were deified by black America, they were equally vilified by white America. Smith's activism before the games had already cost his job washing cars. But both struggled to find work to feed their young families when they returned home from Mexico. Smith's marriage collapsed, Carlos's wife committed suicide. Worse, the threat of retaliatory white violence haunted them. They received regular death threats. Carlos's dog was butchered and left on his porch.

Smith and Carlos had to wait until the 1980s to see their reputations rehabilitated. The Reagan administration's boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics provided a crucial catalyst in their fortunes, proving, after all, that politics and sport are indeed compatible bedfellows. In 2005, Smith and Carlos's return to respectable society was crowned by the unveiling of a statue of their iconic protest on the campus at San Jose State University, their alma mater and the birthplace of OPHR.

The magnetism of that monumental moment continues to captivate and intrigue. For actor and playwright Kwame Kwei-Armah, it is "one of the most definitive expressions of manhood, of service" he has ever seen. And this notion of "service" makes Smith and Carlos's victory stand as relevant today as it was 40 years ago. From Athens to San Francisco, the run-up to this year's Olympic Games in Beijing has witnessed a series of embarrassing anti-China protests. British Olympic team athletes have refused to sign contracts that include "gagging clauses" that stifle their right to protest.

The world today bears little resemblance to the one occupied by Smith and Carlos four decades ago. But one feature that has not changed is injustice and our sensitivity to it. The time is ripe for the next generation of Smiths and Carloses. But only time will tell whether the current crop possesses the political will to use the Beijing stage to carry the baton. |

|

|  |