|  |  |  Editorials | Issues | September 2008 Editorials | Issues | September 2008

Political Reform Gave Push to Drug Lords' Rise in Mexico

Jane Bussey - McClatchy Newspapers Jane Bussey - McClatchy Newspapers

go to original

|

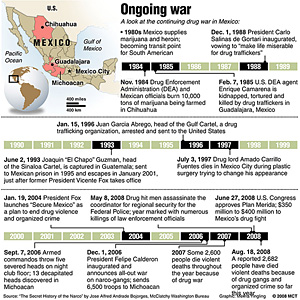

Click image to enlarge | | | |

Mexico City — To understand why drug-related enterprises have become so violent and powerful as to threaten the country's social fabric and government, look no further than the ouster of the former ruling party, many analysts, academics and residents say.

While many factors have contributed to the escalating violence, security analysts in Mexico City trace the origins of the rising scourge to the unraveling of a longtime implicit arrangement between narcotics traffickers and governments controlled by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which lost its monopoly grip on political power starting in the late 1980s.

Set against long-term problems of poverty, badly paid police forces, entrenched corruption and a weak justice system, changes in political control have turned Mexico into a battlefield between organized crime and law-enforcement agents, a combat zone for a terrified society that is only now starting to demand the government take action.

"Narco-trafficking, as well as other organized crime, developed and consolidated under the protection of political power," said Ernesto Lopez Portillo, the founding president of the Institute for Security and Democracy in Mexico City.

"The PRI's fall from power broke the structure set up between the narco-traffickers and power; it broke and fractured this relationship," Lopez Portillo said.

With the government no longer acting as arbitrator of drug gangs, the cartels turned to a retail strategy, buying protection from law enforcement agents and officials across all parties at the local level, experts say.

"The difference between now and the past is that now it is much more democratic; you pay everyone" said Erubiel Tirado, a security expert who is coordinator of the security studies program at the Iberoamerican University in Mexico City. "It is more horizontal and everyone is in on it. This is very, very serious."

The government of President Felipe Calderon is using the Mexican military more than his predecessors because federal authorities do not trust local police forces or prosecutors. Many Mexicans don't either.

"There is no confidence in the institutions of justice, justice is slow and the prisons are filled to the brim," said Sandra Cuello of FTI Consulting Mexico, a global business advisory firm.

The rising bloodshed is also a sign of turf wars, according to security specialists and Mexican law-enforcement sources interviewed by McClatchy Newspapers.

Rival drug cartels are fighting for control of the smuggling routes to the U.S., especially the overland route through the state of Chihuahua to El Paso. About half the 2,673 deaths reported so far this year have been in Chihuahua.

Drug cartels are also fighting to dominate local drug distribution across the nation. For decades Mexico served merely as a transit point for cocaine shipments to the U.S. But now, with smuggling to the U.S. more difficult, leaving cartels with drugs on their hands, excess supplies are sold in Mexico to earn more profits, the experts said.

This rivalry was underscored in late August, when one gang of traffickers strung up banners in cities like Cancun, Monterrey and Nuevo Laredo that railed against the "corruption of the Mexican army and the president" for being "protectors of the drug lords" such as Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman.

Mexican cartels — splintered as they are — have also become powerful global forces, according to Edgardo Buscaglia, an adviser on security to the United Nations and numerous countries who has said Mexican organized crime operates in 38 nations.

Buscaglia, a visiting professor at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico, said that other countries, such as Colombia and Italy, have managed to win the battle against organized crime.

Using the military to fight the traffickers is just one of four parts required for an offensive, like four wheels of the car, Buscaglia said.

Mexico also must attack the cartel's financial system, consisting of thousands of businesses laundering drug money to fund the purchase of weapons and foot soldiers to fight government forces. It also must achieve long-term progress against poverty so that poor youth are not lured to organized crime and forge a real pact among political forces to end corruption.

Mexico doesn't need more money," Buscaglia said. "They need the political will to agree to clean up their act."

Without these four wheels in place, international experience tells us organized crime will not be reduced," he said.

The pressure on political leaders often comes when wealthy elites feel under siege and demand action, the security analysts said.

Some see the possibility Mexico has reached a turning point with the public outcry over the kidnapping and killing of the 14-year-old son of wealthy business leader Alejandro Marti.

Marti has taken a lead in the fight against violence in the weeks since his son's body was found at the end of July in a crime with police involvement.

"Impunity is destroying Mexico," Marti said as he started his public crusade. "If we don't halt impunity, we have to ask ourselves what kind of country we will have?"

(Bussey reports for the Miami Herald.) |

|

|  |