|  |  |  Editorials | Issues | November 2008 Editorials | Issues | November 2008

US Child Labor Going Largely Unchecked

Ames Alexander & Franco Ordonez - The Charlotte Observer Ames Alexander & Franco Ordonez - The Charlotte Observer

go to original

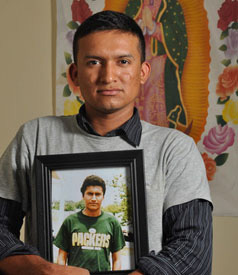

| | Luis Castaneda holds a picture of his brother Nery Castaneda, who died at the age of 17 while working an unsafe job. Many employers are ignoring child labor laws which result in injuries and deaths. (Robert Lahser/The Charlotte Observer) | | |

Nery Castañeda tackled a job that was never intended for kids his age.

One afternoon last fall, the 17-year-old Guatemala native ran a machine to grind damaged pallets into mulch. When a co-worker at the Greensboro plant returned from another task, he didn't see Nery - until he looked inside the shredder.

"A person shouldn't die like this," said older brother Luis. "... He came with a dream and found death."

Decades after the enactment of regulations designed to prevent such tragedies, thousands of youths still get hurt on American jobs deemed unsafe for young workers. On a typical day, more than 400 juvenile workers are injured on the job. Once every 10 days, on average, a worker under the age of 18 is killed, federal statistics show.

Enforcement has waned, despite new evidence that many employers are ignoring child labor laws. U.S. Department of Labor investigations have dropped by nearly half since fiscal year 2000.

"There are lots of kids being asked to do work that's been prohibited for them .- and it's been prohibited because it's dangerous," said Carol Runyan, who heads UNC's Injury Prevention Research Center. "... Our system is failing them."

More than 3 million youths under age 18 have jobs. Regulations prohibit them from doing a variety of hazardous jobs, including most meat-processing work.

But last month, at an immigration raid at a House of Raeford Farms poultry plant in Greenville, S.C., six juveniles were among the workers detained. Three young workers told the Observer they were under 18 when they held jobs at House of Raeford plants requiring them to make thousands of cuts a day with sharp knives. The company says it requires job applicants to present identification showing their age, but not all the documentation is accurate.

At Agriprocessors, a large meatpacking plant in Postville, Iowa, authorities recently charged owners with thousands of child-labor violations after finding that teenage employees were asked to use circular saws, clean floors with powerful chemicals and perform other dangerous tasks.

"The raids in Postville and Greenville show that 15- and 16-year-old kids are doing some of the most dangerous jobs in America," says Reid Maki of the National Consumers League. "... It's time for the U.S. Department of Labor to investigate slaughterhouses and poultry plants."

A study of 16- and 17-year-old construction workers in North Carolina, published in 2006, found that more than 80 percent did tasks that were clearly prohibited. A national survey of young retail and service workers, published in 2007, found that more than half of males and more than 40 percent of females performed prohibited tasks.

Runyan, who co-authored both studies, says much of the blame lies with employers.

"I suspect there are employers who flagrantly disregard the law," she said. "And I suspect there are others who are clueless."

Little to Deter Employers

Employers who flout child-labor rules often face few consequences.

Federal law allows a maximum penalty of $11,000 for each violation, but in 2006 the average penalty was less than $1,000, according to the National Consumers League. Total federal penalties for child labor violations dropped 29 percent from 2000 to 2007.

Federal child labor laws cover large employers, as well as smaller companies engaged in interstate commerce. Most states also have their own child labor laws, which usually cover small employers and impose additional restrictions. But state fines tend to be smaller.

Under N.C. law, the maximum penalty for each violation is $250. When employers fail to ensure juvenile workers get youth employment certificates, the maximum fine is $50 for each violation. That "doesn't seem to be a whole lot of deterrent," says N.C. wage and hour director Jim Taylor, whose office is in charge of enforcing - but not writing - the state's child-labor laws.

In South Carolina, the maximum penalty for violations is $1,000 per person per job.

Federal labor department officials say much has been done to help improve conditions for young workers. Alexander Passantino, administrator for the wage and hour division of the U.S. Department of Labor, told a congressional committee in September that officials have worked to strengthen child-labor laws, raise public awareness and target industries where young workers are likely to be killed or injured. The number of youths killed on the job has declined over the past decade, he noted.

But critics say government has made little progress. Since 2001, injury rates among young workers have remained virtually flat, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Witnesses at the recent congressional hearing were asked whether regulators are doing enough to protect children. Several said the answer was no.

"Much more can and must be done to better protect our young people from hazards and dangers they confront in the workplace," testified Sally Greenberg, executive director of the National Consumers League.

The Perils of Poultry

Meatpacking plants are among the workplaces where better protections are most needed, child advocates say. Many of those plants hire illegal immigrants with false papers, excacerbating the challenge of stopping juveniles from being employed.

In poultry plants, workers are surrounded by dangerous machines and chemicals. And they're often required to make thousands of cuts with sharp knives each day, work that can leave them with lacerations and debilitating nerve and muscle problems, such as carpal tunnel syndrome.

But youths are finding work in such plants, the Observer found.

Elena Luna said she was 16 when she went to work at the Mountaire Farms poultry plant in Lumber Bridge, N.C. At first, she said, a human resources official told her she wasn't old enough. But when she returned with a recommendation from a cousin at the plant, the official asked her whether she could do the work, she said.

"He said, "I don't want to see you in the nursing station or they'll fire me," she said.

On the processing line, she said, she got little training and worked with a supervisor who often yelled at her to hurry up.

Making thousands of cuts with dull knives every day, her hands began to hurt. "Sometimes I couldn't hold the knife," she said.

Luna, who worked under the name Rosaura, said she often wanted to quit, but endured because she needed to repay family members from Mexico who financed her trip to the U.S. - and she thought it was one of the few jobs she could get.

Luna, now 20, said other juveniles also worked at the plant. "I was not the only one," she said. "... Everybody knew."

Mike Tirrell, vice president of operations for Mountaire Farms, said Luna signed paperwork indicating she was 18 when she was hired in 2005. She was fired about 15 months later, after company officials discovered false information on her application, Tirrell said.

He said he could not speak to Luna's specific allegations, but noted that the scenario she described with the human resources official would violate company policy. He disputed that the company has employed numerous underage workers.

The company participates in a voluntary federal program that helps employers determine whether job applicants are legally authorized to work in the country. "We take every step that we can reasonably take to ensure the eligibility of applicants ...," Tirrell said.

Nery's Last Day

Nery Castañeda lived a healthy life. He loved to play soccer and steered clear of alcohol, cigarettes and confrontation, his brother Luis said.

In June 2007, he went to work for Pallet Express, a manufacturer in Greensboro with about 80 employees. He presented his ID, which showed he was 17, his brother said.

Several months into the job, he was asked to operate the pallet shredder, a massive machine that turned damaged pallets into mulch.

On the day of the accident, Nery's co-worker stepped away to get a forklift, Luis said. By the time the co-worker returned, CastaÒeda had been devoured by the shredder.

N.C. OSHA cited the company for eight serious violations, including its failure to put required safety guards on the machine. The agency fined Pallet Express $12,000. The state labor department has also fined the company $250 for putting a juvenile without a youth employment certificate in a hazardous job he shouldn't have been doing.

The family, meanwhile, has filed a lawsuit alleging, among other things, that the company failed to provide Nery with the proper safety gear, training and supervision.

Company vice president Lynn Bell said she could not comment on the case because it is still under investigation.

Luis vividly remembers seeing his brother-in-law's pale face that afternoon in October 2007 when he came to deliver the news that there had been an accident. Luis sank deep into a chair. "No," he recalled moaning.

"I didn't believe it," Luis said. "... He was a kid." |

|

|  |