|  |  |  Editorials | Opinions | March 2009 Editorials | Opinions | March 2009

Going, Going, Gone - Legacy of Gandhi

J. Sri Raman - t r u t h o u t J. Sri Raman - t r u t h o u t

go to original

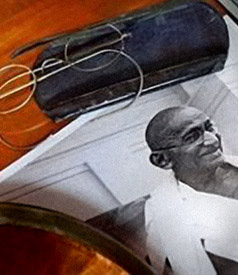

| | An auction for various Mahatma Gandhi artifacts ended with an Indian businessman paying $1.8 million to keep the items in India. (Agencies) |  |

As the hammer came down at an international auction in New York on March 5 and a poor, long-deceased Indian's possessions were declared "sold," a collective sigh was certainly heard across his country. Opinion, however, is divided on the source of the deep sigh.

Was it a sigh of relief from the rulers of India, who had just been rescued from a sticky situation? Or was it a heavy sigh of despair from humbler sections of Indians, who wished that their successive rulers and supporting elites had thought of better ways of remembering Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi?

The reasons for New Delhi's relief were obvious. The event at the Antiquorum Auctioneers in Manhattan had hit the headlines days earlier, and the media had made it appear a major issue of national pride and prestige. The role of an idle spectator was no option to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's regime. To India's millions, Gandhi remained the Mahatma (the Great Soul), even over six eventful decades after his martyrdom. And a general election was just a month and a half away.

The media took the line that the auction might mean the loss of a national legacy, a heritage of history. The Congress Party, leading the ruling United Progressive Alliance (UPA), had always claimed the Mahatma and his hallowed memory as its own special legacy. With the far-right opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) feigning patriotic fury over threats to national sovereignty and security ever since the terrorist strike in Mumbai, Congress and its government could not watch quietly as bids for "Gandhi artifacts" were being reported as a blow to national pride.

The government, however, could not go all out at once to reclaim the heritage for India. Two factors, it was given out, prevented its direct participation in the auction, where the reserve price for the Gandhi articles was fixed at $300,000. In the first place, New Delhi acted coy about participating in "commercialization" of such a sacred national legacy. It was also added, in a pragmatic aside, that the government did not want to be seen paying a fortune for articles of daily use by a frugal Gandhi in these days of recession.

The dilemma was resolved dramatically, when a corporate Indian came to the government's rescue and bought the articles for a whopping $1.8 million at the auction. New Delhi was quick to claim credit for the acquisition, more than suggesting that Vijay Mallya, veteran of many auctions, had acted this time at the government's behest. He was as quick to refute the claim and to assert that New Delhi had made no contact with him, though he added he was only bringing these Gandhi possessions back home and was willing to gift them to the government.

Both the mandarins and Mallya have stuck to their positions ever since and, with their mission accomplished, the media have been happy to move on to other subjects.

Mallya, chairman of the United Breweries and the Kingfisher Airlines, has saved national heritage at a similar auction before. He made big news, too, when he made the highest bid for an ornamental sword of Tipu Sultan, an 18th-century warrior king of south India eulogized as one of the first of India's anti-colonial fighters, at a London auction in 2004 for 175,000 pounds. Mallya also bought players for $111.6 million last year for his own Royal Challengers Bangalore team in the highly popular Indian Premier League (IPL) cricket tournament. The articles he bought in New York, however, could not be more different.

These consisted of pair of round, metal-rimmed spectacles, a pair of sandals, a pocket watch and a brass bowl and plate. Together, the meager belongings of the Mahatma symbolize, more than anything else, his identification with India's impoverished masses. The political legacy he sought to leave for "the poorest of the poor" could have found few takers among the crowd of collectors at international auctions or the calculating investors in India's power games, whether in the government or outside.

Some muffled laughter has been heard in sections of the Indian media about a liquor baron's successful bid for the legacy of Gandhi, an anti-alcohol campaigner. The Mahatma's continuing appeal and relevance, however, have not rested on issues of this kind - any more than his path to glory lay through his preference for goat's milk. The spectacular Mallya trophy must have provoked sadness-tinged laughter for the larger ironies involved.

The ironies abound. A conspicuous one lies in the immediate context. Official India's much-advertised rejoicing over the auction result comes amidst its continuing post-Mumbai efforts to ensure that the "peace process" with Pakistan is not revived. Few in the establishment seem to recall the fact that the Mahatma was assassinated because he wanted India to defeat the designs behind the Partition of 1947 by forging friendship with newly created Pakistan and insisted on New Delhi paying an agreed "compensation" (of 550 million Indian rupees, a dollar then being equivalent to about 3.3 rupees) to Pakistan.

Another obvious irony, of course, lies in a nuclear India getting so exercised over the Gandhi legacy being endangered in the auction. The Mahatma spoke up on nuclear weapons after Hiroshima had stunned him into a day of silence: "The atomic bomb has deadened the finest feelings which have sustained mankind for ages. There used to be so-called laws of war which made it tolerable. Now we understand the naked truth. War knows no law except that of might. The atomic bomb brought an empty victory to the Allied armies. It has resulted for the time being in the soul of Japan being destroyed. What has happened to the soul of the destroying nation is yet too early to see."

Those who label themselves the Mahatma's legatees in million-dollar auctions have pushed India into a nuclear-weapon program, which has raised the country's defense budget to four percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). (India's GDP went up to $1 trillion in 2008, though it may drop by one percent in 2009 as a result of the recession.) The figures must be read, keeping in mind the per-capita income of Indians (about $2 a day), as "the half-naked fakir" always did.

More than just a little doubt has been voiced about the genuineness of the auctioned articles. According to one report, Gita Mehta, adopted daughter of Abha Gandhi, the Mahatma's grandniece in whose lap he breathed his last, signed the authentication for the pocket watch and the bowl from which he had his last meal, but has said she never sold them to James Otis, the collector who sold them at the auction. She insists she gave them to a German scholar, Peter Ruhe, for exhibition in the West.

Jitendra Desai, head of the Navjivan Trust set up by the Mahatma in 1929 and the legal heir to his sparse properties, has told the media that he is not sure the articles are all originals. According to Desai, replicas of such articles have been made before - and stolen now and then. There is no word about how the sandals, said to have been given to a British army officer in 1931 before the Round Table talks on self-rule for India in London, came into the collector's possession.

Professor Lester Kutz of the George Mason University, Virginia, who has reportedly authenticated the items, claims that the collector has also in his possession the Mahatma's blood (from his assassination in January 1948) and his ash (after his cremation). While Darwin's theory is questioned, no doubt has been articulated about such claims. They do not sound indisputably scientific, considering that the first-ever case of DNA profiling was reported in 1985 and that "familial search" for identification of an individual's DNA cannot lead to a final conclusion even today.

More open to question than the articles' genuineness, anyway, is that of any Gandhian spirit behind the gloating over India's success at the auction.

The irony of ironies, perhaps, lies in the announcement of an official promise to waive the import levies on the articles as and when they arrive in India. The Mahatma's concern, when he launched the Salt March in 1930, was about the levy imposed by colonial rulers on "the only condiment of the poor." |

|

|  |