|  |  |  Editorials | Opinions | July 2009 Editorials | Opinions | July 2009

Obama Is Not Roosevelt!

Pascal de Lima & François Ladsous - Les Echos Pascal de Lima & François Ladsous - Les Echos

go to original

July 17, 2009

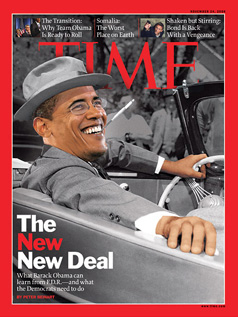

| | Pascal de Lima and François Ladsous argue that Barack Obama is no FDR; his proposed financial regulatory changes distinguish themselves more by what they do not do than by what they reform. (Time Magazine) |  |

The crisis, restructurings, and bankruptcies have not challenged American dominance of the global financial landscape. Although responsible for the present crisis, the United States remains for good and for sure the premier economy, the premier destination for investment capital, and, as a matter of course, the biggest market for financial products! And, once again, that puts American banks in a privileged situation for disseminating methods, practices, and standards across the world and for influencing the management styles of international institutions. All so many reasons why the regulatory reform presented on June 17 by President Obama should be the object of so much interest.

Some expected reform "à la Roosevelt," who, following the Great Depression, took advantage of his popularity to atomize the financial sector with the Glass-Steagall Act. Unfortunately, one is forced to observe that the present proposal seems superficial, even timorous.

We are not calling into question the will to deal with the causes of the excesses that led to and amplified the crisis: derivative products, mortgages, lack of equity capital, insurance problems. Consequently, it is proposed that the Fed's powers be reinforced, that a new consumer protection agency be created and that derivatives be controlled.

But these reforms and these concepts are rarely followed by clear applications that could actually impact the way the banks operate.

With respect to derivative products, it's proposed that a market for the so-called "plain vanilla" products ("futures," "bonds," and other "swaps"), rather simple products the behavior of which is well-understood and which didn't really play a role in the virtual collapse of the system last September, be created. In reality, if one had to designate the guilty, one would have easily zeroed in on the so-called "exotic" credit derivatives, those complex custom-tailored products elaborated one at a time, the volume of which, exchanged by mutual agreement, continued growing relentlessly before the crisis. Well then, the only restriction on those products is a "clearing" platform (a computer system that manages the different phases of a transaction) to allow the products exchanged and their volumes to be followed more easily; perhaps that's an improvement, but it's neither an attempt to regulate nor to restrain them.

Worse, these products were often evaluated by rating agencies that will also escape reform. They will continue to evaluate the clients that pay them. It will continue to be possible to turn out complex derivatives packaged with a seal of approval like so many sausages.

Moreover, if one looks into the way the crisis unfolded in September, one has the right to question what role the Fed played and whether ultimately it's such a good idea to give it more powers. That impression is further reinforced by the fact that equity ratios - which had been virtually abolished for the big American banks in 2004 - have still not been restored, thus defying international conventions on risk management.

Thus does this proposal distinguish itself by what it does not do, rather than by its reforms. Thus, those of us in Europe who believed that a better-regulated financial world could also be more efficient will have to wait for our resolution.

Pascal de Lima is the chief economist with Altran Financial Services and associate professor at the Political Science faculty. François Ladsous is "marketing manager" for Altran Financial Services.

Translation: Truthout French language editor Leslie Thatcher. |

|

|  |