|  |  |  Editorials | Environmental Editorials | Environmental

Couple Spends Days Saving Sea Turtles in Guatemala

Dave Hoekstra - Chicago Sun-Times Dave Hoekstra - Chicago Sun-Times

go to original

January 24, 2010

| | In addition to his work conserving Guatemala's sea turtles, Bernardo Chilin is an avid fisherman in La Barrona, a tiny coastal village that relies on the fishing industry. (Dave Hoekstra/Sun-Times) |

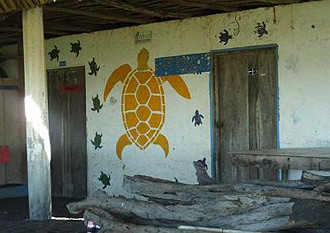

| Project Parlama’s headquarters are next to the hatchery, which Bernardo checks up on nightly. (Dave Hoekstra/Sun-Times)

IF YOU GO: Get Guatemala tourism information on the Web site visitguatemala.com. |  |

La Barrona, Guatemala — Time moves slowly in this Guatemalan village along the Pacific coast.

There are no restaurants in this town of 900 people. Its two hotels have closed. During the darkest hours, the moon is the only source of light in La Barrona (“the sandbar”).

But there are sea turtles. Lots of sea turtles during nesting season, from July to January.

Bernardo Chilin takes care of the turtles. He lives with his wife, Sonia, and their five children on the outskirts of town. They have a three-bedroom cinderblock house on land peppered with mango, coconut and tamarind trees.

A forest ranger at a nearby estuary, Bernardo has a coop of 200 chickens in his backyard. He sold about 40 of them to his neighbors on New Year’s Eve. Sonia is the ringleader for the town’s Avon ladies.

Bernardo has worked with the volunteer sea turtle conservation group Project Parlama, named for the turtle species. Guatemala is unique in allowing its communities to collect and sell turtle eggs, but only if they work with a local hatchery that incubates donated eggs and returns hatchlings to the sea.

Environmental management is bequeathed to the locals. But it was the five-person Project Parlama group from England, Spain and the United States that helped Bernardo build an 8-by-12-foot wooden hatchery along the ocean. Since 2005, they’ve used money from Guatemalan conservation organizations. Funding will run out next month.

In this Central American country, 75 percent of the population lives below poverty level, according to the CIA World Factbook.

Bernardo walks to the hatchery seven nights a week, often with his loyal black mutt, Bobby. He carries an old flashlight.

When he finds eggs on the beach, he gently buries them in the hatchery. The eggs incubate for 46 days. He also checks for hatchlings, on the lookout for crabs, gulls and red ants hungry for eggs. He often sleeps at the hatchery for a few hours in a colorful hammock he made by hand.

If it’s a magical night, Bernardo finds olive-colored baby turtles wiggling for liberty in the sand. He picks them up and releases them into the timeless ocean.

I stayed with Bernardo and his family during a New Year’s vacation with my Chicago girlfriend, who has been part of the volunteer effort. Just getting to La Barrona was an adventure. We flew into Guatemala City and spent a night in Antigua before heading to La Barrona on the country’s legendary “chicken buses,” so called because people cram into them like fowl.

Bus service isn’t so dependable. On the way to La Barrona, our bus broke down. We were put on another bus. That bus broke down, too. We finished the next 30 miles of the journey on the back of a pick-up truck before transferring to a passenger van in the El Salvador-Guatemala border town of Pedro de Alvarado.

During our visit, we were lucky enough to find seven baby turtles in the hatchery on New Year’s Eve.

We attended a fiesta at the home of a rancher in La Barrona, which got electricity for the first time in the 1990s. The rancher is the richest man in town and throws a free New Year’s Eve party every year for the community. There was dancing to cumbia music. Fireworks. Gallo beer. Food. A few pistols.

Bernardo, 48, did not attend the party. He took his family to church.

He’s spent his entire life in La Barrona. He saw his first turtle at age 12.

“I was with my [El Salvadorian] mom because she went to the beach with us at night,” he said through translation over a kitchen table filled with black beans and tortillas. “We found two that night. You could put a mark in the sand to say you had found that one and nobody would mess with it. You’d then go look for other ones. Now it’s more difficult because the population of the town has multiplied.”

And the turtle population has dropped.

According to the Marine Turtle newsletter, people along the Pacific used to be able to collect enough turtle eggs to fill a 100-pound bag. That was in the ’60s. Today, you’re lucky to find even one nest on the beach.

La Barrona relies on the fishing industry for survival. Bernardo is an accomplished fisherman who reels in shrimp, snapper and catfish from the ocean and estuary.

“This is how we earn our living,” he said in soft tones. “If we conserve the turtles, we make a better living. It is part of our culture in this country to eat turtle eggs. That’s never going to go away.”

On Guatemala’s Atlantic coast, adult turtles are killed for their meat and shells. On La Barrona’s Pacific coast, it’s considered a sin to kill an adult turtle.

Adult turtles in the sea are threatened by shrimping boats that trawl with nets not equipped to extract the turtles.

Bernardo estimated that one of every 100 turtles he sets out to sea will survive.

“That is the law of nature,” he said. “When they are born in nature, they come out and know the sound of the sea. They know the way to go.”

Bernardo guesses he has seen 36,000 baby sea turtles in his lifetime.

“It is very emotional for me,” he said. “Think about watching a birth. That’s what it feels like.”

Young boys help Bernardo comb the beach for eggs. They’re rewarded with modest prizes when they bring eggs to the hatchery.

I asked Bernardo why ecotourists would visit La Barrona as opposed to turtle conservation programs in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, and Trinidad and Tobago, for example.

“We have a virgin beach, which is important for nesting of turtles,” he answered. “Because there is no light pollution. We have a virgin mangrove forest where there’s lots of different birdwatching. There’s a canal where you can fish. Because of all these things tourists would leave here feeling satisfied with what they have seen.

“We need someone who will promote tourism. I hope that will happen someday because our community can benefit from it.” |

|

|  |