|  |  |  Editorials | Environmental Editorials | Environmental

Altered Corn Slowly Takes Root in Mexico

Jean Guerrero - WSJ.com Jean Guerrero - WSJ.com

go to original

December 09, 2010

| | (Agance France-Presse/Getty Images) |  |

Mexico City — Mexico, the birthplace of corn, is edging toward the use of genetically modified varieties to lower its dependence on imports, but strong opposition among some growers and environmentalists, who see altered corn as a threat to native strains, has kept the wheels turning slowly.

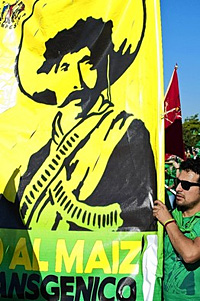

An activist carrying a 'No to Transgenic Corn' banner through the streets of Cancun, Mexico, this week during a demonstration coinciding with United Nations climate talks.

Monsanto Co., DuPont Co.'s Pioneer Hi-Bred unit and Dow Chemical Co,'s Dow AgroSciences recently completed small, controlled experiments in northern Mexico with genetically modified corn, and are seeking government authorization to enter a "pre-commercial" phase, expanding the growing area to nearly 500 acres from 35 acres.

The trials began in October 2009, four years after Mexico lifted an 11-year moratorium on genetically modified corn—or maize—to which scientists have added desirable traits like pest resistance.

Many farmers and environmentalists, however, fear that altered corn will cross-breed with the nearly 60 documented native maize varieties, transforming the biology of the grain, a dietary staple with deep cultural significance here. By contrast, genetically modified cotton, alfalfa and soybeans are widely accepted and cultivated on nearly 250,000 acres across the country.

"We are the children of corn. It's our life, and we need to protect it," said José Bernardo Magdaleno Velasco, a corn producer in Venustiano Carranza in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, where he grows two native varieties. According to Mayan legend, the gods created humans from corn. The plant is still used in some indigenous religious rituals.

Two types of genetically modified corn are produced commercially in 16 countries, led by the U.S., but almost nowhere has their introduction met the resistance it has in Mexico.

Protests have been staged across the country, and a coalition of 300 groups has led a campaign called "Sin maiz no hay pais," or "Without corn there is no country."

Opening the doors to genetically modified corn, its opponents fear, would contaminate native varieties, such as the red Xocoyol or the black Yautsi, increase dependence on foreign companies and possibly harm the nation's environment and health.

Supporters of the modified seeds say they would help Mexico win agricultural independence from the U.S., from which it imports as much as nine million tons of yellow corn annually for livestock feed, most of it genetically modified.

In Mexico, where the average corn yield is around 8.2 tons per acre, and many subsistence growers get little more than a ton per acre, the seeds could also help reduce hunger and the use of environmentally harmful pesticides, supporters say.

"Being the principal crop of Mexico, maize is where we can have the largest impact on the rural sector," said José Manuel Madero, president of Monsanto Mexico. He said the company's hybrid seeds have already quadrupled yields in some parts of Mexico over the past 60 years, and he thinks its genetically modified corn could increase yields by another 15% to 30%. If the corn sector embraces biotechnology, Mexico could become self-sufficient in corn over the next 10 years, Mr. Madero said. "What's important is that the farmer be able to choose the technological package that he wants."

Government officials have said Mexico's recent experiments with genetically modified corn have been successful, in that the corn proved resistant to either pests or herbicides.

Still, a decision on moving to the next phase, in which it will evaluate the economic benefits of the corn, is still pending.

"It would be sad if…our biodiversity should impede the use of the technology here," said Reynaldo Ariel Alvarez Morales, head of the Inter-Secretarial Commission on Biosecurity of Genetically Modified Organisms, which coordinates the agencies in charge of making a decision.

The moratorium on genetically modified corn was put in place in 1998 to protect the maize native to Mexico, where the crop originated from a plant called teocinte. In the decade or so since then, the tide has started to shift, although planting of altered corn still isn't allowed in designated centers of origin and diversity, such as Chiapas and Oaxaca, where the nearly 60 native varieties predominate.

Proponents say that if imported genetically modified corn hasn't already contaminated native varieties, neither will planting the country's own genetically modified corn, an argument opponents reject.

Multiple studies, including ones conducted by the National Biodiversity Council in Mexico and the National Ecology Institute, found that native corn varieties in some off-limit southern areas already contain genes from modified corn.

"The only way the native corn in Oaxaca will be contaminated is if a producer from Oaxaca brings [the genetically modified corn] and plants it voluntarily. And why would he do that? Because he sees an interest. He doesn't see it as ugly. And any producer can do that right now," said Fabrice Salamanca, president of Agrobio, which represents the biotech companies seeking to introduce the new corn.

Some opponents are also worried about pollen flow, but scientists say that even in the best conditions, corn can't pollinate other corn more than a couple of miles away. Other scientists say the danger to native maize stems from the fact that indigenous species, well-adapted to specific regions, may lose those advantages if they mix with genetically modified corn.

If a native variety inherits pest-resistance from genetically modified corn, for example, it might stop being able to evolve improvements to its inherent defense mechanisms.

Some opponents also worry that the altered corn will hurt the environment. In some parts of the U.S., pests have evolved resistance to pest-resistant corn, leading to an increase in the use of pesticides, rather than the intended decrease, and some countries have temporarily banned the planting of genetically modified corn out of environmental concerns.

Proponents say that hybrid corn, which has existed in Mexico for 60 yearsand is improved by regular cross-breeding, has already mixed with native maize varieties without causing any problems. Since genetically modified corn is hybrid corn with one additional gene inserted from a different species, they say the difference would be minimal. |

|

|  |