Mexico City, Mexico - On April 18th, Mexico City shook and rattled as a 7.2-magnitude earthquake sent people scurrying into the streets. Tremors are a frequent scare for the city’s 20 million or so residents, who experience dozens of small shudders a year.

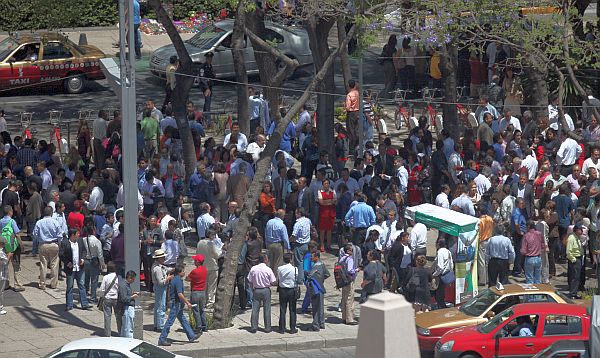

But the panic is lessened by the fact that people know the earthquake is coming a couple of minutes before the ground starts to tremble. Before last month’s big rumble, many Mexicans had already filed outside to await the wobble in safety - away from falling ceilings. Nowhere else in the world is able to forecast earthquakes in this way.

How do the Mexicans do it?

In 1985 whole neighborhood of the capital were reduced to rubble by an almighty 8.1-magnitude terremoto, which flattened buildings all over the city. More than 10,000 people are estimated to have been killed. The damage was devastating: parts of the city have yet to be rebuilt.

The impact on society was greater still. Some historians believe it contributed to the end of the hegemony of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, whose ineffectiveness in the aftermath of the earthquake undermined its claim to be the party that knew best how to govern. The scale of the disaster, and the inefficiency of the official response, galvanized civil society like never before.

Mexico City’s residents resolved that next time they would be prepared.

Within a few years they had come up with an ingenious early-warning system. The epicenter of earthquakes hitting Mexico City, which lies roughly in the center of the country, is usually to the south, where the North American continental plate rubs up against the Cocos plate. This means that quakes are felt first in states such as Oaxaca, on the Pacific coast. So seismologists installed sensors in the south of the country that detect the first tremors and send a warning to the capital.

The seismic wave moves at about 7,000 miles per hour. That sounds fast, but it means that it takes the quake nearly two minutes to travel the 200 miles from Oaxaca to Mexico City. Meanwhile the sensors' signal arrives virtually instantaneously in Mexico City, where alarms are sounded, giving people just enough time to scamper out into the street before the earthquake arrives.

Why can no other country develop an early-warning system like this?

Japan has something similar, and California is trying to put one together. But they generally give much less time to take cover than in Mexico.

The reason is that Japan and California — and indeed most earthquake-prone places — sit right on top of faultlines, so earthquakes strike moments after the first tremors are felt. Mexico City, by contrast, lies hundreds of miles away from the nearest fault, meaning that it takes a minute or two for the wave to arrive.

A place so far away from a faultline would never normally be so vulnerable; but Mexico City is built on a former lakebed, giving it jelly-like subsoil which amplifies even tiny tremors into mighty window-rattlers. The strength of its early-warning system, therefore, is built on the weakness of the city's foundations.

Original Story