|  |  |  Health & Beauty | July 2008 Health & Beauty | July 2008

Drug Addiction Soars in Mexico

Chris Hawley - USA Today Chris Hawley - USA Today

go to original

| | BOXTEXT | | |

Agua Prieta, Mexico — Carlos Antonio López started using crack at age 11 to kill the pain of his mother's death.

"I started with marijuana, but after a while it didn't fill me up anymore," he says. "Then I started on crack. You get obsessed, you can't think about anything else."

Now 18, López is in his sixth stint in rehab.

Not so long ago, stories like López's were unusual in Mexico, where drug addiction had never been a widespread problem. These days, the country is dealing with an unprecedented epidemic of drug use that is partly a result of better U.S. border enforcement, experts say.

The new border fence and intensified patrols by both Mexican and U.S. federal agents have made it harder for Mexican cartels to get drugs into the USA. As a result, more narcotics remain in Mexico where they are sold to local consumers, says Marcela López Cabrera, director of the Monte Fenix clinic in Mexico City, which trains drug counselors.

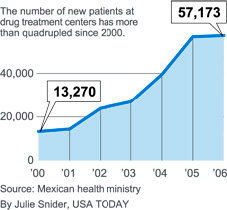

The number of new patients at Mexican treatment centers has more than quadrupled since 2000. The health ministry has announced plans to build 300 new rehab centers, triple the current total, to deal with the overflow.

"We used to be mainly a country of transit for drugs. Now we've become a consumer," says Ricardo Sánchez, director of research for the health ministry's rehab centers.

Mexican President Felipe Calderón warned last month that cartels are no longer just trying to get drugs to the USA, but generate consumers "here in Mexico who will buy them, and buy them for the rest of their lives."

'Never get rid of obsession'

In Agua Prieta, across the border from Douglas, Ariz., the drug peddlers sell crack, meth, heroin, cocaine and marijuana from cars that cruise through the dirt streets. The addicts call them "ice cream trucks."

On the edge of town, recovering addicts gather for their noon pep talk at a private shelter. It's a grim place to have to kick a habit. The dormitories are dimly lit rooms with bare concrete floors. Mentally ill patients wander around a penned-in area with a few chairs. Meals are cooked on an outdoor fire.

The detox area, where patients spend their first days, is a room with a single light bulb off the dormitory. There is no door to muffle screams of newcomers going through withdrawal.

A few years ago, the shelter averaged 50 residents at a time. Now there are 92, and they are getting younger as the price of drugs drops, says assistant director Miguel Salgado. A rock of crack costs as little as $2.50 in Agua Prieta, he says.

As bleak as conditions are, López says the shelter is better than the world outside. "I don't like to go out," he says. "Here I'm safe. Out there, you never know, because you never get rid of the obsession for more drugs."

Changing market pressures

President Bush has credited Calderón for sending 20,000 troops to border cities, killing or arresting kingpins and extraditing dozens of suspects to the USA. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, the reduced flow of drugs north has helped push cocaine prices higher in many U.S. cities; a gram of pure cocaine sold for about $118.70 in spring 2007.

Meanwhile, cocaine prices in Mexico have plummeted to "practically nothing," says Irving Aguilar, medical director at the Clinicas Claider treatment center in Mexico City. A gram of cocaine sells in central Mexico for about $19, he says. Crack is $9.50 a rock and getting cheaper.

Crack addicts began outnumbering alcoholics at his clinic in 2003 and now account for about 60% of patients.

Mexican addicts have also begun using drugs — particularly heroin and crystal methamphetamine — that until recently had barely appeared in the local market, Sanchez says.

"Before we didn't have crystal (meth) here in Agua Prieta," says Sergio Panduro, a recovering addict who is a counselor at the shelter. "Now it's here, and we have more youth doing it."

"There are more girls, too, and that's a big change," Panduro says.

Other factors may weigh in. The arrest of top cartel leaders has spawned a class of smaller-time drug smugglers who need the easy money from selling locally, says Arturo Arango, a researcher with the Citizens' Institute for Studies on Crime.

The U.S. crackdown on illegal immigrants has also led to the deportation of Mexicans who have been exposed to America's drug culture.

A recent health department study in border cities showed that 23% of Mexican youths who had lived in the USA had tried drugs, compared with 5% of those who had never left Mexico.

All the changes mean it will be hard to beat back the dope peddlers, say recovering addicts and their counselors.

There are at least two crack houses within walking distance of the Agua Prieta rehab facility, Salgado says, and the "ice cream trucks" run all night.

Hawley is Latin America correspondent for USA TODAY and The Arizona Republic |

|

|  |