|  |  |  Health & Beauty | November 2009 Health & Beauty | November 2009

Who Knew I Was Not the Father?

Ruth Padawer - New York Times Ruth Padawer - New York Times

go to original

November 22, 2009

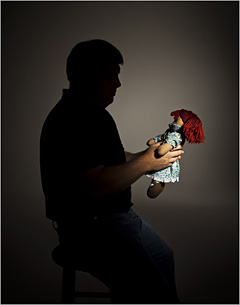

| | Mike L. has remained a father to a daughter that wasn't really "his." (Horacio Salinas/New York Times) |  |

I.

It was in July 2007 when Mike L. asked the Pennsylvania courts to declare that he was no longer the father of his daughter. For four years, Mike had known that the girl he had rocked to sleep and danced with across the living-room floor was not, as they say, “his.” The revelation from a DNA test was devastating and prompted him to leave his wife — but he had not renounced their child. He continued to feel that in all the ways that mattered, she was still his daughter, and he faithfully paid her child support. It was only when he learned that his ex-wife was about to marry the man who she said actually was the girl’s biological father that Mike flipped. Supporting another man’s child suddenly became unbearable.

Two years after filing the suit that sought to end his paternal rights, Mike is still irate about the fix he’s in. “I pay child support to a biologically intact family,” Mike told me, his voice cracking with incredulity. “A father and mother, married, who live with their own child. And I pay support for that child. How ridiculous is that?”

Yet despite his indignation — and despite his court filings seeking to end his obligations as a father — Mike loves his daughter. Every other weekend, the 11-year-old girl, L., lives in Mike’s house in a quiet suburban neighborhood in Western Pennsylvania. Her bedroom there is decorated to reflect her current passion: there’s a soccer bedspread, soccer curtains and a soccer-ball night light. On her bed is an Everybody Loves Me pillow covered with transparent sleeves filled with photos of her and Mike, the man she calls “Daddy,” canoeing, fishing and sledding together.

As the two of them prepared breakfast together one Saturday in June, just after L. finished fifth grade, Mike sang a little ditty about how she was his favorite daughter. A few minutes later, when he noticed L. sneaking a piece of raw biscuit dough, he poked her. She looked at him impishly until they both giggled.

“Just because our relationship started because of someone else’s lie,” he said later, “doesn’t mean the bond that developed isn’t real.” Still, his love became entangled with humiliation and outrage, and each child-support payment stung so much that he felt compelled to take a stand on principle. In doing so, he also took the small but terrifying risk of losing his child.

Mike’s conundrum is increasingly playing out in courts across the country, a result of political, social and technological shifts. Stricter federal rules have pressed states to chase down fathers and hold them responsible for children born outside of marriage, a category that includes 40 percent of all births. At the same time, DNA tests have become easier, cheaper and more reliable. Swiping a few cheek cells and paying a couple hundred dollars can answer the question that has plagued men since the dawn of time: Am I really the father?

One hundred and twenty-two years ago, the playwright August Strindberg meditated on this quandary. “The Father” is the story of a cavalry captain whose wife hints that he might not be the father of the daughter he adores. Consumed with doubt, he rages at his wife: “I have worked and slaved for you, your child, your mother, your servants . . . because I thought myself the father of your child. This is the commonest kind of theft, the most brutal slavery. I have had 17 years of penal servitude and have been innocent.”

Without a biological tie, the captain cries, his paternal love is without foundation. But even as he laments that his daughter may not be his, the captain seeks consolation from his childhood nursemaid. With his mind unraveling, he rests his head in her lap and speaks of the comfort of “mother” — because that was the nursemaid’s role, biology notwithstanding.

Strindberg never reveals whether the captain’s fears were justified, and perhaps the answer doesn’t matter. As long as the captain believed he had a biological link to his child, their relationship was meaningful. It is that link, or perhaps the fear of its absence, that drives men today to DNA tests.

Over the last decade, the number of paternity tests taken every year jumped 64 percent, to more than 400,000. That figure counts only a subset of tests — those that are admissible in court and thus require an unbiased tester and a documented chain of possession from test site to lab. Other tests are conducted by men who, like Mike, buy kits from the Internet or at the corner Rite Aid, swab the inside of their cheeks and that of their putative child’s and mail the samples to a lab. Of course, the men who take the tests already question their paternity, and for about 30 percent of them, their hunch is right. Yet as troubled as many of them might be by that news, they are even more stunned to discover that many judges find it irrelevant. State statutes and case law vary widely, but most judges conclude that these men must continue to raise their children — or at least pay support — no matter what their DNA says. The scientific advance that was supposed to offer clarity instead reveals just how murky society’s notions of fatherhood actually are.

Ruth Padawer is an adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. Her last article for the magazine was about a dating site for “sugar daddies.” |

|

|  |