|  |  |  Health & Beauty Health & Beauty

US Veteran Care: More Questions Than Solutions

Deb Weinstein - t r u t h o u t Deb Weinstein - t r u t h o u t

go to original

July 17, 2010

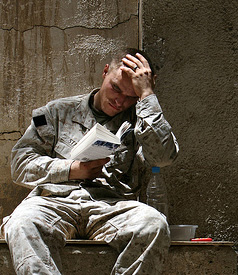

| | (slagheap) |  |

Washington - Two days after regulations went into effect making it easier for veterans to seek treatment for PTSD, members of the House Committee on Veterans Affairs met Wednesday with veterans, the mother of an Iraq war veteran who committed suicide, and members of the Veterans Health Administration to discuss other ways to help veterans get the help they need.

The discussion, which spanned over two hours, boiled down to two key points: suicide rates among veterans are far too high, and the Department of Defense, Veterans Affairs and Armed Services have a lot to tackle if they want to reverse the trend.

The witnesses were quick to concede that there has been incremental progress when it comes to helping veterans, and cited the 1-800-273-TALK suicide prevention hotline, which was launched in 2007, as an example of progress. However, the witnesses said the hotline is a last-resort fix, and that what is needed is a continuum of watchfulness and contact from the time civilians become soldiers to well beyond their return to civilian life. According to retired Warrant Officer Melvin Cintron, who served in the Gulf War and Operation Iraqi Freedom, part of this watchfulness includes a system that understands that mental health isn't simply a matter of going from being sound to unsound, but a process. Right now, Cintron said, the military sees only status A or status B. Cintron said that to be able to halt the migration between extremes could mean the difference between becoming suicidal and not. "By the time they reach the suicide hotline, it is too late," he said.

According to an April 26 article in the Army Times, 18 veterans commit suicide every day, and the Department of Defense says the military is on track to surpass last year's suicide rate, which set a high for the number of suicides in the last 30 years.

The way Cintron and Linda Bean, whose son Coleman, 25, killed himself in 2008, described it, veterans need a web of care that draws in family members and community organizations. The goal, they said, would be to make communities, not just individuals, aware of the help that is available to veterans. This would make finding the information not just more accessible to those in need, but would also make it easier for outsiders to help. Clarity, Bean said, is sorely lacking. Describing the Department of Defense and Veterans Affairs websites as dense, she said the information that should be immediately accessible - with something akin to a "PTSD and other click here" callout - is so impossible to find, and said that searching is intimidating.

The military's struggle to communicate with veterans and their families is also apparent in their advertising efforts. To paraphrase Timothy Embree, legislative assistant with the group Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, the VA is throwing money at media and doesn't understand it. For example, Embree said his group was excited to hear that the VA was promoting the TALK hotline on 21,000 buses across the United States. According to Embree, it was a complete failure. "The ad has over 30 small print words . . . in the short time in which a bus passes, a veteran would have to pass the bus repeatedly to read the hotline number." Embree said the VA has also failed at social networking, saying Twitter and Facebook should be about fostering a feeling of connection between those in need of care and those providing it. Instead, Embree said, the VA uses these networking sites for self-promotion. "We need [messaging] that's not just 'this new hospital has 20 new doctors' . . . we need to give a face to the VA," and have VA staff use social networking sites to share their experiences so veterans can identify common ground, he said.

The Representatives on the panel were in agreement that more needed to be done, and offered up, along with the witnesses, a trifecta approach to effective care:

If you can afford to contribute, please help keep Truthout free for everyone.

Outreach that brings the VA to veterans if the veterans won't visit the VA: This could include physically sending representatives to veterans, allowing private practitioners to help, or having what amounts to a buddy system in which officers check in on their former recruits.

A campaign that removes the stigma from seeking help: The tactic: public service announcements and an advertising campaign that would make seeking medical help feel like a regular part of post-deployment life. "Great programs are worthless if service members are ashamed to use them," IAVA's Embree noted.

Intervention that starts when first assigned a uniform: This would include training officers to recognize mental stress during service. It would also include having officers and/or veterans groups check in with veterans on a regular basis after deployment to see how they are coping. For Committee Chairman Mitchell (D-Arizona) and Retired Warrant Officer Cintron, medical staff wouldn't have to do the check-ins. "It doesn't take a fancy PhD to ask 'How are you getting on?'" Mitchell said. According to Cintron, most of the time, veterans feel better knowing they are talking with someone who has had a similar experience.

For Rep. John J. Hall (D-New York), outreach also means giving post-military life the same attention as the promises made during recruiting, noting that there is little hesitation to promote the Army and Marines during prime time "where the 30-second spots cost the most money," he said, noting, when "it comes time to help [veterans] find the resources they need to stay healthy . . . we do it on the cheap," with ads that run late at night when broadcasters have nothing else to air.

When relaying the day's testimony to Paul Sullivan, executive director of the Washington-based interest group Veterans for Common Sense, his reaction was positive to an extent. On the idea that was proffered to allow non-VA medical staff to step in when the VA is physically out of reach, he said, "Absolutely, yes." On outreach to civic groups and religious groups and normalizing care, he was unwavering. "The VA needs to do this every single day without exception across the country," he said, noting that for the outreach to be effective, in terms of normalizing care and acknowledging that disorders such as PTSD can take years to surface, an outreach program would have to continue for decades, not years.

When it came to the idea of a buddy system, Sullivan was less enthusiastic. "That's the way it's always worked, that's why there are veterans organizations" he said.

Nor was he placated by what he considers a major oversight - that the behaviors associated with mental stress, such as alcoholism, fighting, and drug abuse, are not being treated as symptoms, but as crimes. As an example, Sullivan cited a July 14 article in the New York Times about Fort Bliss, TX. This article, which discusses the way combat stress manifests itself, talks about how six at least six of a unit's former soldiers are in jail for behavior that are indicative of duress.

Sullivan also finds fault with the military's ability to staff up on qualified medical professionals and the military's track record when it comes to accountability. "I know from first hand knowledge speaking with VA employees and veterans that the VA is still turning away suicidal veterans" he said.

The hearing wound down after just over two hours of testimony. Rep. Timothy Walz (D-Minnesota), whose opening statements said the goal should be zero suicides, acknowledgement that, "We may never get there but we have an obligation to try." Rep. Walz had a question: "We've got to get to the front end of this instead of chasing our tails at the back end. Are we getting any closer?"

For Sullivan, the question was more basic. If the outreach and campaign to destigmatize getting help are a success, will the VA have enough doctors to handle the influx?

Deb Weinstein is an intern at Truthout. |

|

|  |