|  |  |  Health & Beauty | May 2009 Health & Beauty | May 2009

A Journey Through Darkness

Daphne Merkin - New York Times Daphne Merkin - New York Times

go to original

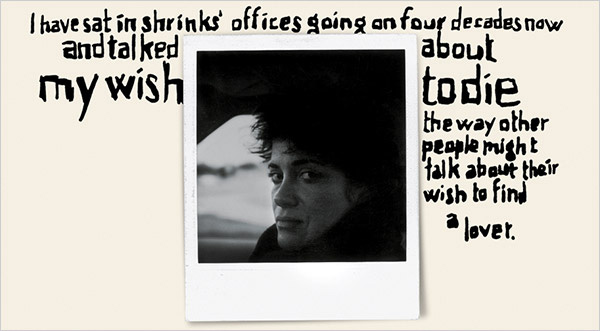

| | (Lettering by James Victore; Photograph From Daphne Merkin) |  |

It is a sparkling day in mid-June, the sun out in full force, the sky a limpid blue. I am lying on my back on the grass, listening to the intermittent chirping of nearby birds; my eyes are closed, the better to savor the warmth on my face. As I soak up the rays I think about summers past, the squawking of seagulls on the beach and walking along the water with my daughter, picking out enticing seashells, arguing over their various merits. My mind floats away into a space where chronology doesn’t count: I am back on the beach of my adolescence, lost in a book, or talking to my old college chum Bethanie as we brave the bay water in front of her parents’ house in Connecticut, where she comes to visit every summer.

In the 20 or so minutes of “fresh air” allotted after lunch (one of four such breaks on the daily schedule), I try to forget where I am, imaging myself elsewhere than in this fenced-off concrete garden bordered by the West Side Highway on one side and Riverside Drive on the other, planted with patches of green and a few lonely flowers, my movements watched over by a more or less friendly psychiatric aide. Soggy as my brain is from being wrenched off a slew of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications in the last 10 days, I reach for a Coleridgian suspension of disbelief, ignoring the roar of traffic and summoning up the sound of breaking waves.

I have only to open my eyes for the surreal scene to come back into my immediate line of vision, like a picnic area without picnickers: two barbecue grills, bags of mulch that seem never to be opened, empty planters, clusters of tables and chairs, the entire area cordoned off behind a high mesh fence. Looking out onto the highway overpass there is a green-and-white sign indicating “Exit — West 178th Street”; nearer to the entrance another sign explains: “The Patients’ Park & Garden is for the use of patients and their families only, and for staff escorting patients. It is NOT for staff use.”

I can see R., the most recent addition to our dysfunctional gang of 12 on 4 Center, sitting on a bench in his unseasonal cashmere polo, smoking a cigarette and tapping his foot with equal intensity. On either side of him are ragtag groups of people culled from several units of the hospital, including the one I am on, which is devoted primarily to the treatment of patients with depression or eating disorders. (The anorexic girls, whom R. refers to as “the storks,” are in various phases of imperceptible recovery and tend to stick together.) The garden is also home to patients from 4 South, which caters to patients from within the surrounding Washington Heights community, and 5 South, which treats patients with psychotic and substance-abuse disorders.

The people on 4 Center, hidden away as it is in a small building, have next to no contact with the other units; we might as well be on different planets. Then again, as those who suffer from it know, intractable depression creates a planet all its own, largely impermeable to influence from others except as shadow presences, urging you to come out and rejoin the world, take in a movie, go out for a bite, cheer up. By the time I admitted myself to the hospital last June after a downhill period of six months, I felt isolated in my own pitch-darkness, even when I was in a room full of conversation and light.

Depression — the thick black paste of it, the muck of bleakness — was nothing new to me. I had done battle with it in some way or other since childhood. It is an affliction that often starts young and goes unheeded — younger than would seem possible, as if in exiting the womb I was enveloped in a gray and itchy wool blanket instead of a soft, pastel-colored bunting. Perhaps I am overstating the case; I don’t think I actually began as a melancholy baby, if I am to go by photos of me, in which I seem impish, with sparkly eyes and a full smile. All the same, who knows but that I was already adopting the mask of all-rightness that every depressed person learns to wear in order to navigate the world?

I do know that by the age of 5 or 6, in my corduroy overalls, racing around in Keds, I had begun to be apprehensive about what lay in wait for me. I felt that events had not conspired in my favor, for many reasons, including the fact that in my family there were too many children and too little attention to go around. What attention there was came mostly from an abusive nanny who scared me into total compliance and a mercurial mother whose interest was often unkindly. By age 8 I was wholly unwilling to attend school, out of some combination of fear and separation anxiety. (It seems to me now, many years later, that I was expressing early on a chronic depressive’s wish to stay home, on the inside, instead of taking on the outside, loomingly hostile world in the form of classmates and teachers.) By 10 I had been hospitalized because I cried all the time, although I don’t know if the word “depression” was ever actually used.

As an adult, I wondered incessantly: What would it be like to be someone with a brighter take on things? Someone possessed of the necessary illusions without which life is unbearable? Someone who could get up in the morning without being held captive by morose thoughts doing their wild and wily gymnastics of despair as she measures out tablespoons of coffee from their snappy little aluminum bag: You shouldn’t. You should have. Why are you? Why aren’t you? There’s no hope, it’s too late, it has always been too late. Give up, go back to bed, there’s no hope. There’s so much to do. There’s not enough to do. There is no hope.

Surely this is the worst part of being at the mercy of your own mind, especially when that mind lists toward the despondent at the first sign of gray: the fact that there is no way out of the reality of being you, a person who is forever noticing the grime on the bricks, the flaws in the friends — the sadness that runs under the skin of things, like blood, beginning as a trickle and ending up as a hemorrhage, staining everything. It is a sadness that no one seems to want to talk about in public, at cocktail-party sorts of places, not even in this Age of Indiscretion. Nor is the private realm particularly conducive to airing this kind of implacably despondent feeling, no matter how willing your friends are to listen. Depression, truth be told, is both boring and threatening as a subject of conversation. In the end there is no one to intervene on your behalf when you disappear again into what feels like a psychological dungeon — a place that has a familiar musky smell, a familiar lack of light and excess of enclosure — except the people you’ve paid large sums of money to talk to over the years. I have sat in shrinks’ offices going on four decades now and talked about my wish to die the way other people might talk about their wish to find a lover.

Then there is this: In some way, the quiet terror of severe depression never entirely passes once you’ve experienced it. It hovers behind the scenes, placated temporarily by medication and renewed energy, waiting to slither back in, unnoticed by others. It sits in the space behind your eyes, making its presence felt even in those moments when other, lighter matters are at the forefront of your mind. It tugs at you, keeping you from ever being fully at ease. Worst of all, it honors no season and respects no calendar; it arrives precisely when it feels like it.

MY MOST RECENT BOUT, the one that landed me on 4 Center, an under-the-radar research unit at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, asserted itself on New Year’s Eve, the last day of 2007. The precipitating factors included everything and nothing, as is just about always the case — some combination of vulnerable genetics and several less-than-optimal pieces of fate.

Despite my grim mood, I had somehow or other managed to put on makeup, pull on clothes, affix pearl earrings and go to a civilized old-New York type of dinner, where we talked of ongoing things — children, schools, plays to see, reasons to live as opposed to reasons to die. But even as I talked and laughed with the other guests, my thoughts were dark, scrambling ones, ruthless in their sniping insistence. You’re a failure. A burden. Useless. Worse than useless: worthless. Shortly past midnight, I watched the fireworks over Central Park and stared into the exploding bursts of color — red, white and blue, squiggles of green, streaks of purple, balls of silver, sparks of champagne. My 17-year-old daughter, Zoë, was standing nearby, and as I looked into the fireworks I sent entreaties into the sky. Make me better. Make me remember this moment of absorption in fireworks, the energy of the thing. Make me go forward. Stop listening for drum rolls. Pay attention to the ordinary calls to engage, messages on your answering machine telling you to buck up, it’s not so bad, from the ex, siblings, people who care.

For the next six months I countered the depression with everything I had, escaping into the narcotic of reading, taking on a few writing assignments (all of which I delivered weeks, if not months, late), meeting friends for dinner, teaching a writing class and even taking a trip to St. Tropez with a close friend. I gobbled down my usual medley of pills — Lamictal, Risperdal, Wellbutrin and Lexapro — and wore an Emsam patch. (I have not been free of psychotropic medication for any substantial period since my early 20s.) But this was not a passing episode that a schedule full of distractions and medication could assuage. Although many depressions resolve themselves within a year, with or without treatment, sometimes they take hold and won’t let go, becoming incrementally worse with each passing day, until suicide seems like the only exit. This was one of those depressions.

In the weeks leading up to my checking into 4 Center, I had gone from being able to put on a faltering imitation of mental health to giving up all pretense of a manageable disguise. Since I found it painful to be conscious, I had stopped doing much of anything except sleeping. Mornings were the worst: I got up later and later, first 11, then noon, and now it was more like 2 in the afternoon, the day three-quarters gone. “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day,” observed the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, a depressive 19th-century Jesuit priest. I don’t think I’ve ever met a depressed person who wanted to get out of bed in the morning — who didn’t experience the appearance of day as a call to burrow further under the covers, the better to embrace the vanished night.

When I was awake (the few hours that I was), I felt a kind of lethal fatigue, as if I were swimming through tar. Phone messages went unanswered, e-mail unread. In my inert but agitated state I could no longer concentrate long enough to read — not so much as a newspaper headline — and the idea of writing was as foreign to me as downhill racing. (James Baldwin: “No one works better out of anguish at all; that’s an incredible literary conceit.”) I barely ate — there is no more effective diet than clinical depression — and had dropped 30 pounds. I had essentially withdrawn from communication. When I did speak, it was mostly about my wish to commit suicide, a wish that was never all that far from my mind but at times like these became insistent.

Although some tiny part of me retained a dim sense of the more functioning person I once was — like a room with a closed door that was never entered anymore — it became increasingly difficult to envision myself ever inhabiting that version of myself again. There had been too many recurrent episodes, too many years of trying to fight off this debilitating demon of a thing. It has been called by different names at different times in history — melancholia, malaise, cafard, brown study, the blues, the black dog, acedia — and has been treated as a spiritual malady, a failure of will, a biochemical malfunctioning, a psychic conundrum, sometimes all at once. Whatever it was, it had come to define me, filling out all the available space, leaving no possibility of a “before” or an “after.” Instead I harbored the hallucinatory conviction that I had stayed around the scene of my own life too long — that I was, in some unyielding sense, ex post facto.

I had also quite literally ground to a halt, like a machine that had hit a glitch and frozen on the spot. I moved at a glacial pace and talked haltingly, in a voice that was lower and flatter than my usual one. As I discovered from my therapist and psychopharmacologist — both of whom argued that I belonged in a hospital now that my depression had taken on “a life of its own,” beyond the exertions of my will — there was a clinical name for my state: “psychomotor retardation.” My biology, that is, had caught up and joined hands with the immediate psychodynamic stressors that precipitated my nosedive — the lingering aftermath of the death two years earlier of my mother, with whom I had a complicated relationship; the imminent separation from my college-age daughter, who was my boon companion; therapy that took a wrong turn; a romance that went awry. (Much as we would like to explain clinical depression by making it either genetics or environment, bad wiring or bad nurturing, it is usually a combination of the two that sets the illness off.)

And yet I resisted my doctors’ suggestion that I check myself into a hospital. It seemed safer to stay where I was, no matter how out on a ledge I felt, than to lock myself away with other desperadoes in the hope that it would prove effective. Whatever fantasies I once harbored about the haven-like possibilities of a psychiatric facility or the promise of a definitive, once-and-for-all cure were shattered by my last stay 15 years earlier. I had written about the experience, musing on the gap between the alternately idealized and diabolical image of mental hospitals versus the more banal bureaucratic reality. I discussed the continued stigma attached to going public with the experience of depression, but all this had been expressed by the writer in me rather than the patient, and it seemed to me that part of the appeal of the article was the impression it gave that my hospital days were behind me. It would be a betrayal of my literary persona, if nothing else, to go back into a psychiatric unit.

What’s more, after a lifetime of talk therapy and medication that never seemed to do more than patch over the holes in my self, I wasn’t sure that I still believed in the concept of professional intervention. Indeed, I probably knew more about antidepressants than most analysts, having tried all three categories of psychotropics separately or in combination as they became available — the classic tricyclics, the now-unfashionable MAO inhibitors (which come with a major drawback in the form of dietary restrictions) as well as the newer S.S.R.I.’s. and S.N.R.I.’s. I was originally reluctant to try pills for something that seemed so intrinsic to who I was — the state of mind in which I lived, so to speak — until one of my first psychiatrists compared my emotional state to an ulcer. “You can’t speak to an ulcer,” he said. “You can’t reason with it. First you cure the ulcer, then you go on to talk about the way you feel.” My current regime of pills incorporated the latest approach, which called for the augmentation of a classic antidepressant (Effexor) with a small dose of a second-generation antipsychotic (Risperdal). From the time I was prescribed Prozac in my early 20s before it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration, you could say that the history of depression medication and my personal history came of age together, with me in the starring role of a lab rat.

Of course, none of the drugs work conclusively, and for now we are stuck with what comes down to a refined form of guesswork — 30-odd pills that operate in not completely understood ways on neural pathways, on serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine and what have you. No one, not even the psychopharmacologists who dispense them after considering the odds, totally comprehends why they work when they work or why they don’t when they don’t. All the while the repercussions and the possible side effects (which include mild trembling on the one end to tardive dyskinesia, a rare condition that causes uncontrollable grimacing, on the other end) are shunted to the side until such time as they can no longer be ignored.

THE ONE THING PSYCHIATRIC hospitals are supposed to be good for is to keep you safe. But I was conflicted even about so primary an issue as survival. I wasn’t sure I wanted to ambush my own downward spiral, where the light at the end of the tunnel, as the mood-disordered Robert Lowell once said, was just the light of the oncoming train. I saw myself go splat on the pavement with a kind of equanimity, with a sense of a foretold conclusion. Self-inflicted death had always held out a stark allure for me: I was fascinated by people who had the temerity to bring down the curtain on their own suffering — who didn’t hang around, moping, in hopes of a brighter day. I knew all the arguments about the cowardice and selfishness (not to mention anger) involved in committing suicide, but nothing could persuade me that the act didn’t require a perverse sort of courage, some steely embrace of self-extinction. At one and the same time, I have also always believed that suicide victims don’t realize they won’t be coming this way again. If you are depressed enough, it seems to me, you begin to conceive of death as a cradle, rocking you gently back to a fresh life, glistening with newness, unsullied by you.

Still, one flesh-and-blood reality stood in my way: I had a daughter I loved deeply, and I understood the irreparable harm it would cause her if I took my own life, despite feeling that if I truly cared about her I would free her from the presence of a mother who was more shade than sun. (What had Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton done with their guilt feelings? I wondered. Were they more narcissistic than I or just more strong-willed?) It was because of my daughter, after all, that I had given voice to my “suicidal ideation,” as it’s called, in the first place, worrying how she would get along without me. At the same time, I recognized that, for a person who was really set on ending it all, speaking your intention aloud was an act of self-betrayal. After all, in the process of articulating your death wish you were alerting other people, ensuring that they would try to stop you.

The real question was why no one ever seemed to figure this grim scenario out on her own, just by looking at you. This was enraging in and of itself — the fact that severe depression, much as it might be treated as an illness, didn’t send out clear signals for others to pick up on; it did its deadly dismantling work under cover of normalcy. The psychological pain was agonizing, but there was no way of proving it, no bleeding wounds to point to. How much simpler it would be all around if you could put your mind in a cast, like a broken ankle, and elicit murmurings of sympathy from other people instead of skepticism (“You can’t really be feeling as bad as all that”) and in some cases outright hostility (“Maybe if you stopped thinking about yourself so much . . . ”).

One more factor worked to keep me where I was, exiled in my own apartment, a prisoner of my affliction: the specter of ECT (electro-convulsive therapy). My therapist, a modern Freudian analyst whom I had been seeing for years and who had always struck me as only vaguely persuaded of the efficacy of medication for what ailed me — when I once experienced some bad side effects, he proposed that I consider going off all my pills just to see how I would fare, and after doing so I plummeted — had suddenly, in the last 10 days before I went into the hospital, become a cheerleader for undergoing ECT. I don’t know why he grabbed on to this idea, why the sudden flip from chatting to zapping, other than for the fact that I had once wildly thrown it out — for the drowning, any life raft will do. Then, too, ECT, which causes the brain to go into seizure, was back in fashion for treatment-resistant depression after going off the radar in the ’60s and ’70s in the wake of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” Perhaps I had frightened him with my insistent talk of wanting to cut out for good; perhaps he didn’t want to be held responsible for the death of a patient who compulsively wrote about herself and would undoubtedly leave evidence that would tie him to her. But his shift from a psychoanalytic stance that focused on the subjective mind to a neurobiological stance that focused on the hypothesized workings of the physical brain left me scared and distrustful.

1 | 2 |  |

|

|  |