Guatemala - In a remote northeastern corner of Guatemala, archaeologists, excavating the ruins of the ninth-century Maya complex of Xultun, say they have found what appears to be the work-place for the town's scribe. The dwelling, dating from about AD 813, is adorned with magnificent pictures of the king and other royals, and what could be the oldest known Mayan calendar.

This year has been particularly controversial for some people because of the internet-fueled belief that the Mayan calendar predicts the end of the world on December 21, 2012. Researchers for the journal Science say the calculations on the new find, written on the plaster equivalent of a modern scientistís whiteboard, strongly reinforces the idea that the Mayan calendar projects 7,000 years into the future.

The astronomical and calendrical calculations at the find seem to be precursors to those in the well-known Dresden Codex, a much more sophisticated series of Mayan formulas recorded in a book made from bark-paper from the 11th or 12th century, and they may yield insights into how that work was prepared.

The discoveries, made in a region of lowland rainforest, are unusually well preserved since artwork and writings from the area are easily destroyed by the jungle humidity. "The state of preservation was remarkable," said archaeologist William A. Saturno of Boston University, who led the expedition.

"Weíve never seen anything like it," added archaeologist David Stuart of the University of Texas at Austin, who is deciphering the hieroglyphs. "For the first time we get to see what may be actual records kept by a scribe, whose job was to be official record keeper of a Maya community."

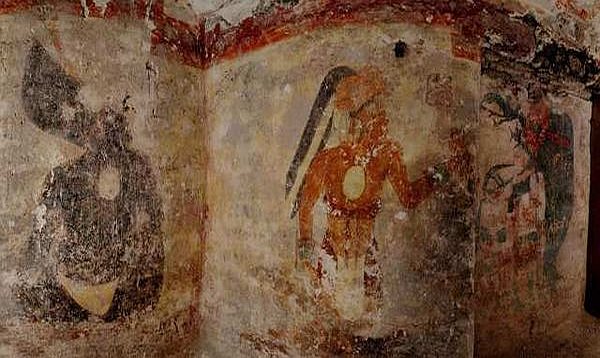

The ruins were actually discovered in 1915 but not excavated or thoroughly studied until recently because of its isolated location. The 40 square-foot room seems to have been filled with rubble before other structures were built on top of it and there are three surviving plaster walls, say the researchers. On one wall is a painting of a king, wearing a headpiece with blue feathers.

The portrait of the king was found in a rounded niche on the north wall of the structure and bone curtain rods would have allowed a drape to be drawn over it to hide it.

Near him are numbers that correspond to previously known cycles in the Mayan calendar ó and others that researchers had not seen before; rough sketches of people and several different areas with columns of numbers and calculations, either written with red and black paint or inscribed in plaster. Some areas appear to have been plastered over several times, as if to provide fresh writing surfaces, according to the archaeologists.

Not all of the writings have been deciphered yet, but some clearly describe the 260-day ceremonial calendar, the 365-day solar calendar, the 584-day cycle of Venus, and the 780-day cycle of Mars. Another calendar nearby is comprised of 17 baktuns, or 400-year periods, encompassing an additional 4,000 years beyond the 21st century.

Proponents of the doomsday idea said 2012 would mark the conclusion of the last of the 13 baktuns that make up the Mayan calendar. But the calendar uncovered in Xultun has 17 baktuns, and Stuart said the Mayas method of time measurement included units much larger than even the baktun.

|

Saturno, like other scientists who have studied their civilization, says that the Maya appear not to have thought much, at least in their writings, about an end to the world. "The Mayan calendar is going to keep going for billions, trillions, octillions of years into the future," he said.

Stuart acknowledged that "we donít know exactly what this is noting," but the Maya were looking at 'patterns in the sky' and intermeshing them mathematically."

Among other things, the calculations showed which god was the patron of each day and month, marked celestial events tied to religious ceremonies, and allowed astronomers to calculate the dates of eclipses; which were important in rituals.

"The ancient Maya predicted the world would continue; that 7,000 years from now, things would be exactly like this," Saturno said. "While modern man keeps looking for endings, the Maya were looking for a guarantee that nothing would change. Itís an entirely different mindset."

The home containing the calendar was part of a large residential complex and 99.9 percent of the site has yet to be explored, according to Saturno, who spoke of "the great wealth of scientific material that remains in Guatemala in the Mayan area for us to discover."